How the India-Bangladesh Enclaves Problem Was Jump-Started in 2007 Towards its 2015 Solution: A Case Study of Academic Impact on Policy

June 8, 2015 — drsubrotoroy“Haksar, Manmohan and Sonia” (2014)

August 7, 2014 — drsubrotoroyMy article “Haksar, Manmohan and Sonia” appeared today as an op-ed with the New Indian Express http://t.co/bRnQI1hrwy

In the summer of 1973, my father, then with India’s embassy in Paris, brought home two visiting colleagues separately, to advise me before I headed to undergraduate studies at the LSE. One was G Parthasarathi, India’s envoy in Karachi during the 1965 war [CORRECTION Nov 2015: Parthasarathi had left shortly before the war; Kewal Singh arrived as the war started] when my father had been acting head in Dhaka; G P was marvelous, strictly advising I do the hardest things I could find at LSE, namely mathematical economics. The other visitor was Manmohan Singh.

Manmohan, then in his early 40s, asked to meet me alone, and we plunged quickly into a heated debate about the demerits (as I saw them) and merits (as he saw them) of the USSR and its “planning”. He was taken aback by the lad, and at the end of his 40-minute visit said he would write to his friend Amartya Sen at LSE about me. An ambiguous, hardly laudatory letter of introduction to Amartya arrived, which I duly but reluctantly carried; I wish I had kept a copy but xeroxing was not yet a word back then.

When I told my father about the debate, he to my surprise said Manmohan was extremely highly thought of in government circles, had degrees from both Cambridge and Oxford, and was expected to become prime minister of India some day!

That prediction, more than 30 years before Manmohan did become India’s PM, was almost certainly a reflection of the opinion of P N Haksar, still at the height of his power as Indira Gandhi’s right-hand man. In a 2005 interview with Mark Tully, Manmohan acknowledged Haksar being his mentor in politics who brought him into government in early 1971. My father himself was sent by Haksar to the Paris embassy in anticipation of Indira’s November 1971 visit on her diplomatic tour before the Bangladesh War.

Fast forward to the afternoon of March 22, 1991, at Delhi’s Andhra Bhavan. I had met Rajiv Gandhi through S S Ray on September 18, 1990, and given him results of a perestroika-for-India project I had led at the University of Hawaii since 1986.On September 25, 1990, Rajiv formed a group consisting of Gen K V Krishna Rao, M K Rasgotra, V Krishnamurthy, S Pitroda and myself to write a modern agenda and manifesto for elections Rajiv said he expected by April 1991. Krishnamurthy later brought in A M Khusro to the group, and all these persons were present at the March 22 meeting—when I was unexpectedly challenged by Rasgotra demanding to know what Manmohan Singh would say about all this liberalisation and efficiency (and public goods, etc.) I had proposed.

That was the first mention of Manmohan in post-Indira politics. I replied I did not know what he would say but knew he had been on a project for Julius Nyerere, that the main thing was to get the world to see the Congress at least knew its economics and wanted to improve India’s woeful credit-standing.

The next day, on the lawns of 10 Jan Path, Rajiv launched Krishna Rao’s book titled Prepare or Perish. Rajiv was introduced on the occasion by none other than P N Haksar. I talked to Haksar briefly, mentioning his sending my father to Paris in 1971 and my father’s old friends the Kaul brothers, the elder being Haksar’s brother-in-law and the younger being Manmohan’s first boss in government. Haksar seemed unwell but was clearly delighted to have returned to favour after falling out with Indira during Sanjay’s regime.

The March 22, 1991, meeting was also one of several occasions when I, a complete layman on security issues and new to Delhi and in my 30s, warned as vehemently as I could that Rajiv seemed to my layman’s eyes extremely vulnerable to assassination. Absolutely nothing was done in response by anyone, other than saying I should probably speak to “Madame”!

One man’s response, in 2007 and 2014 publications, has been to deny he knew me at all and claim the group came to exist without me—when in fact it was created by Rajiv as a sounding board one week after I gave him the academic project results I had led since 1986. This same man had excitedly revealed to me on September 25, 1990, that his claim to a doctoral degree originated in the USSR in the 1970s; he has always concealed his experiences in that country. After Rajiv’s assassination, he rose to much background influence with Sonia, and one of his protégés is now apparently influential with Mr Modi too.

Sonia Gandhi I met only once to convey my condolences in December 1991, and give her a copy of a tape of conversations between Rajiv and myself during the Gulf war in January that year. She seemed a taciturn figure in deep grief, and apparently continued with the seven-year period of mourning traditional in her culture of origin.

Natwar Singh and Sanjaya Baru, in their recent publications, may have allowed basic misinterpretations of events to distract from what may be informative in their experience.

Natwar has said Haksar was central in May 1991 in the move (purportedly on behalf of Rajiv’s newly bereaved widow) to first ask S D Sharma to take the PM’s job, which Sharma declined. If so, this was a failed attempt by the “Haksar axis” of unelected non-politicians to maintain control of events. Natwar claims it was only then Sonia chose P V N Rao. In reality, P V N R was a highly respected leader who, though due to retire, was the acknowledged senior member in a group of regional leaders including S S Ray, Sharad Pawar and others. The Haksar axis failed to stop P V N R’s rise to the top job, though it managed to get Haksar’s protégé to become finance minister. Sonia was hardly involved.

As for Manmohan becoming Sonia’s PM, a senior Lok Sabha Congress leader with PM ambitions himself told me of his own accord in December 2001 that it was certain she would not take the top job herself and it was generally presumed Manmohan would get one term—the denouement of the Haksarian prediction my father made to me in 1973 in Paris. Contrary to Baru’s claim or even Manmohan’s own self-knowledge, it was never any “accident” that he became PM of India.

Finally on the issue of files being shown, the man named as the conduit is someone I became related to in law back in 1981. He and Manmohan, too, would have been sticklers for the rules. The real issue is this: given the 1970s brand of Soviet influence on the Congress, would anyone have said it was Kosygin as PM who did or could ever wield more power than Brezhnev the party boss? Of course not. The same with Manmohan and Sonia in India.

One of the men Rajiv introduced me to on 25-9-1990 at 10 JanPath (No, Rajiv did not realize who he was…) 2023

July 3, 2014 — drsubrotoroyMuch as I might love Russia, England, France, America, I despise their spies & local agents affecting poor India’s policies: Memo to PM Modi, Mr Jaitley, Mr Doval & the new Govt. of India: Beware of Delhi’s sleeper agents, lobbyists & other dalals (2014)

1 July 2014

Dear Bibek,

The very elderly man I refer to as “Sonia’s Lying Courtier” herein

https://independentindian.com/2007/11/25/sonias-lying-courtier/

is someone who has known you, leading up to your appointment as Director at Sonia’s “Rajiv Gandhi Institute” and later. He has now published a purported memoir whose main aim is to conceal his Soviet connections during the Brezhnev era 1960s-1970s, besides trying to rub my name out from my role with Rajiv in 1990-1991. The woman journalist in Delhi who is named as having ghost-written his new book is someone you know quite well too.

The man was someone whom I worked with and who was introduced to me by Rajiv Gandhi on 25/9/1990, a Soviet trained “technocrat” who had inveigled himself into Rajiv’s circle as he had been a favoured one of Indira (presumably via PN Haksar) when he returned from the USSR. He was also the link explaining, again via PN Haksar, how Manmohan first became FM in 1991 after Rajiv’s assassination, then how Manmohan came to Sonia’s notice and attention, and was later crucial in the so-called Rajiv Gandhi Foundation and in the formation of Sonia’s so-called National Advisory Council.

His mandate was to keep INC policies predictable and agreeable in the areas of Soviet/Russian interest, in which he seems to have succeeded during the Sonia-Manmohan regime.

He found me an unknown force, and worked to edge me out, despite the fact the 25/9/90 group was formed by Rajiv as a sounding-board for the perestroika-for-India project I led in America since 1986 and which I brought to Rajiv the week before on 18/9/90…

I send this to you as a word of caution as you are clearly close to Mr Modi and Mr Doval, yet none of you may know the man’s background and intent, even in his dotage. Certainly the purported memoir written by the woman journalist is something whose main aim is to conceal the man’s Soviet/Russian background. Had it been an honest intent, he would have had no need to conceal any of this but would have addressed his own Russian experience openly and squarely. He may have had his impact already with the new Government, I do not know.

For myself, I have been openly rather pro-Russia on the merits of the current Ukraine issue, but, as you will appreciate, I despise any kind of deep foreign agent seeking to control Indian policy in long-term concealment.

Cordially

Suby Roy

Sonia’s Lying Courtier with Postscript 25 Nov 2007, & Addendum 30 June 2014

30th June 2014

“Sonia’s Lying Courtier” (see below) has now lied again! In a ghost-written 2014 book published by a prominent publisher in Delhi!

He has so skilfully lied about himself the ghost writer was probably left in the dark too about the truth.

**The largest concealment has to do with his Soviet connection: he is fluent in Russian, lived as a privileged guest of the state there, and before returning to the Indian public sector was awarded in the early 1970s a Soviet degree, supposedly an earned doctorate in Soviet style management!**

How do I know? He told me so personally! His Soviet degree is what allowed himself to pass off as a “Dr” in Delhi power-circles for decades, as did many others who were planted in that era. He has also lied about himself and Rajiv Gandhi in 1990-1991, and hence he has lied about me indirectly.

In 2007 I was gentle in my exposure of his mendacity because of his advanced age. Now it is more and more clear to me that exposing this directly may be the one way for Sonia and her son to realise how they, and hence the Congress party, were themselves influenced without knowing it for years…

25 November 2007

Two Sundays ago in an English-language Indian newspaper, an elderly man in his 80s, advertised as being “the Gandhi family’s favourite technocrat” published some deliberate falsehoods about events in Delhi 17 years ago surrounding Rajiv Gandhi’s last months. I wrote at once to the man, let me call him Mr C, asking him to correct the falsehoods since, after all, it was possible he had stated them inadvertently or thoughtlessly or through faulty memory. He did not do so. I then wrote to a friend of his, a Congress Party MP from his State, who should be expected to know the truth, and I suggested to him that he intercede with his friend to make the corrections, since I did not wish, if at all possible, to be compelled to call an elderly man a liar in public.

That did not happen either and hence I am, with sadness and regret, compelled to call Mr C a liar.

The newspaper article reported that Mr C’s “relationship with Rajiv (Gandhi) would become closer when (Rajiv) was out of power” and that Mr C “was part of a group that brainstormed with Rajiv every day on a different subject”. Mr C has reportedly said Rajiv’s “learning period came after he left his job” as PM, and “the others (in the group)” were Mr A, Mr B, Mr D, Mr E “and Manmohan Singh” (italics added).

In reality, Mr C was a retired pro-USSR bureaucrat aged in his late 60s in September 1990 when Rajiv Gandhi was Leader of the Opposition and Congress President. Manmohan Singh was an about-to-retire bureaucrat who in September 1990 was not physically present in India, having been working for Julius Nyerere of Tanzania for several years.

On 18 September 1990, upon recommendation of Siddhartha Shankar Ray, Rajiv Gandhi met me at 10 Janpath, where I handed him a copy of the unpublished results of an academic “perestroika-for-India” project I had led at the University of Hawaii since 1986. The story of that encounter has been told first on July 31-August 2 1991 in The Statesman, then in the October 2001 issue of Freedom First, then in January 6-8 2006, September 23-24 2007 in The Statesman, and most recently in The Statesman Festival Volume 2007. The last of these speaks most fully yet of my warnings against Rajiv’s vulnerability to assassination; this document in unpublished form was sent by me to Rajiv’s friend, Mr Suman Dubey in July 2005, who forwarded it with my permission to the family of Rajiv Gandhi.

It was at the 18 September 1990 meeting that I suggested to Rajiv that he should plan to have a modern election manifesto written. The next day, 19 September, I was asked by Rajiv’s assistant V George to stay in Delhi for a few days as Mr Gandhi wished me to meet some people. I was not told whom I was to meet but that there would be a meeting on Monday, 24th September. On Saturday, the Monday meeting was postponed to Tuesday 25th September because one of the persons had not been able to get a flight into Delhi. I pressed to know what was going on, and was told I would meet Mr A, Mr B, Mr C and Mr D. It turned out later Mr A was the person who could not fly in from Hyderabad.

The group (excluding Mr B who failed to turn up because his servant had failed to give him the right message) met Rajiv at 10 Janpath in the afternoon of 25th September. We were asked by Rajiv to draft technical aspects of a modern manifesto for an election that was to be expected in April 1991. The documents I had given Rajiv a week earlier were distributed to the group. The full story of what transpired has been told in my previous publications.

Mr C was ingratiating towards me after that first meeting with Rajiv and insisted on giving me a ride in his car which he told me was the very first Maruti ever manufactured. He flattered me needlessly by saying that my PhD (in economics from Cambridge University) was real whereas his own doctoral degree had been from a dubious management institute of the USSR. (Handling out such doctoral degrees was apparently a standard Soviet way of gaining influence.) Mr C has not stated in public how his claim to the title of “Dr” arises.

Following that 25 September 1990 meeting, Mr C did absolutely nothing for several months towards the purpose Rajiv had set us, stating he was very busy with private business in his home-state where he flew to immediately. Mr D went abroad and was later hit by severe illness. Mr B, Mr A and I met for luncheon at New Delhi’s Andhra Bhavan where the former explained how he had missed the initial meeting. Then Mr B said he was very busy with his house-construction, and Mr A said he was very busy with finishing a book for his publishers on Indian defence, and both begged off, like Mr C and Mr D, from any of the work that Rajiv had explicitly set our group. My work and meeting with Rajiv in October 1990 has been reported previously.

Mr C has not merely suppressed my name from the group in what he has published in the newspaper article two Sundays ago, he has stated he met Rajiv as part of such a group “every day on a different subject”, another falsehood. The next meeting of the group with Rajiv was in fact only in December 1990, when the Chandrashekhar Government was discussed. I was called by telephone in the USA by Rajiv’s assistant V George but I was unable to attend, and was briefed later about it by Mr A.

When new elections were finally announced in March 1991, Mr C brought in Mr E into the group in my absence (so he told me), perhaps in the hope I would remain absent. But I returned to Delhi and between March 18 1991 and March 22 1991, our group, including Mr E (who did have a genuine PhD), produced an agreed-upon document. That document was handed over by us together in a group to Rajiv Gandhi at 10 Janpath the next day, and also went to the official political manifesto committee of Narasimha Rao, Pranab Mukherjee and M. Solanki.

Our group, as appointed by Rajiv on 25 September 1990, came to an end with the submission of the desired document to Rajiv on 23 March 1991.

As for Manmohan Singh, contrary to Mr C’s falsehood, Manmohan Singh has himself truthfully said he was with the Nyerere project until November 1990, then joined Chandrashekhar’s PMO in December 1990 which he left in March 1991, that he had no meeting with Rajiv Gandhi prior to Rajiv’s assassination but rather did not in fact enter Indian politics at all until invited by Narasimha Rao several weeks later to be Finance Minister. In other words, Manmohan Singh himself is on record stating facts that demonstrate Mr C’s falsehood.

The economic policy sections of the document submitted to Rajiv on 23 March 1991 had been drafted largely by myself with support of Mr E and Mr D and Mr C as well. It was done over the objections of Mr B, who had challenged me by asking what Manmohan Singh would think of it. I had replied I had no idea what Manmohan Singh would think of it, saying I knew he had been out of the country on the Nyerere project for some years.

Mr C has deliberately excluded my name from the group and deliberately added Manmohan Singh’s instead. What explains this attempted falsification of facts – reminiscent of totalitarian practices in communist countries? Manmohan Singh was not involved by his own admission, and as Finance Minister told me so directly when he and I were introduced in Washington DC in September 1993 by Siddhartha Shankar Ray, then Indian Ambassador to the USA.

A possible explanation for Mr C’s mendacity is as follows: I have been recently publishing the fact that I repeatedly pleaded warnings that I (even as a layman on security issues) perceived Rajiv Gandhi to have been insecure and vulnerable to assassination. Mr C, Mr B and Mr A were among the main recipients of my warnings and my advice as to what we as a group, appointed by Rajiv, should have done towards protecting Rajiv better. They did nothing — though each of them was a senior man then aged in his late 60s at the time and fully familiar with Delhi’s workings while I was a 35 year old newcomer. After Rajiv was assassinated, I was disgusted with what I had seen of the Congress Party and Delhi, and did not return except to meet Rajiv’s widow once in December 1991 to give her a copy of a tape in which her late husband’s voice was recorded in conversations with me during the Gulf War.

Mr C has inveigled himself into Sonia Gandhi’s coterie – while Manmohan Singh went from being mentioned in our group by Mr B to becoming Narasimha Rao’s Finance Minister and Sonia Gandhi’s Prime Minister. If Rajiv had not been assassinated, Sonia Gandhi would have been merely a happy grandmother today and not India’s purported ruler. India would also have likely not have been the macroeconomic and political mess that the mendacious people around Sonia Gandhi like Mr C have now led it towards.

POSTSCRIPT: The Congress MP was kind enough to write in shortly afterwards; he confirmed he “recognize(d) that Rajivji did indeed consult you in 1990-1991 about the future direction of economic policy.” A truth is told and, furthermore, the set of genuine Rajivists in the present Congress Party is identified as non-null.

Did Jagdish Bhagwati “originate”, “pioneer”, “intellectually father” India’s 1991 economic reform? Did Manmohan Singh? Or did I, through my encounter with Rajiv Gandhi, just as Siddhartha Shankar Ray told Manmohan & his aides in Sep 1993 in Washington? Judge the evidence for yourself. And why has Amartya Sen misdescribed his work? India’s right path forward today remains what I said in my 3 Dec 2012 Delhi lecture!

August 23, 2013 — drsubrotoroyDid Jagdish Bhagwati “originate”, “pioneer”, “intellectually father” India’s 1991 economic reform? Did Manmohan Singh? Or did I, through my encounter with Rajiv Gandhi, just as Siddhartha Shankar Ray told Manmohan & his aides in Sep 1993 in Washington? Judge the evidence for yourself. And why has Amartya Sen misdescribed his work? India’s right path forward today remains what I said in my 3 Dec 2012 Delhi lecture!

[See also “I’m on my way out”: Siddhartha Shankar Ray (1920-2010)…An Economist’s Tribute”; “Rajiv Gandhi and the Origins of India’s 1991 Economic Reform”; “Three Memoranda to Rajiv Gandhi 1990-1991″

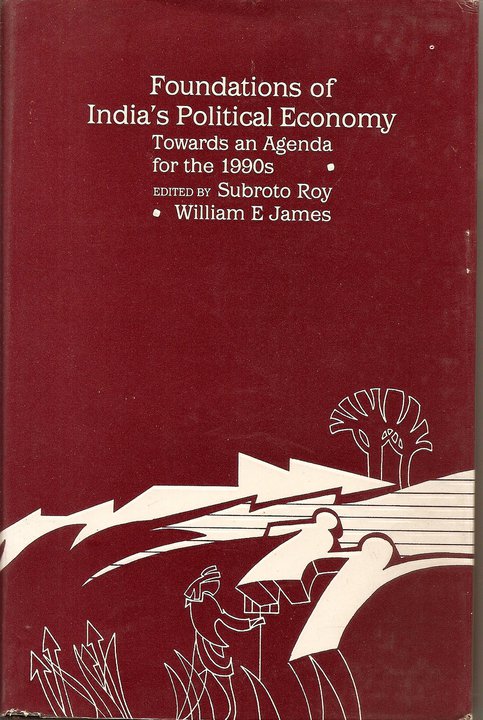

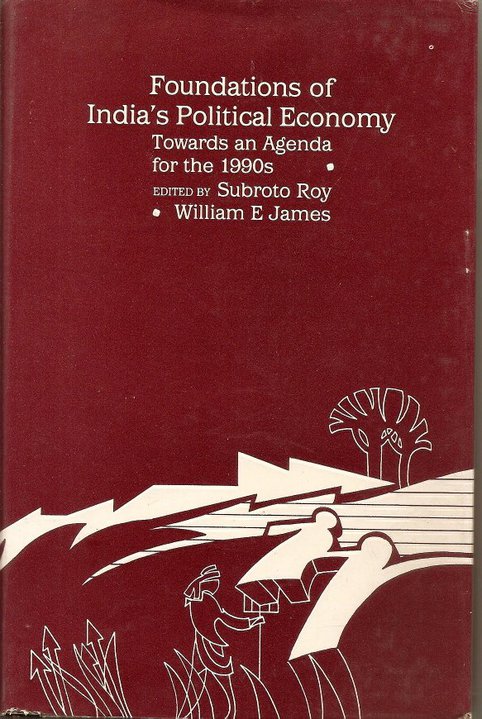

Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s edited by Subroto Roy & William E James, 1986-1992… pdf copy uploaded 2021

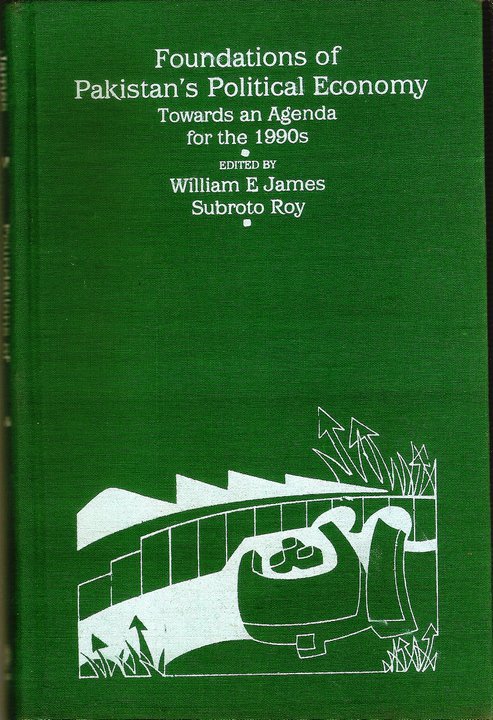

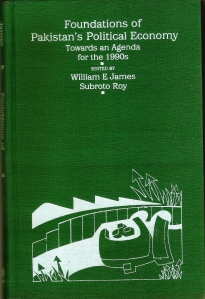

Foundations of Pakistan’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s, edited by William E James & Subroto Roy, 1986-1993… pdf copy uploaded 2021

Critique of Amartya Sen: A Tragedy of Plagiarism, Fake News, Dissimulation

Contents

Part I: Facts vs Fiction, Flattery, Falsification, etc

1. Problem

2. Rajiv Gandhi, Siddhartha Shankar Ray, Milton Friedman & Myself

3. Jagdish Bhagwati & Manmohan Singh? That just don’t fly!

4. Amartya Sen’s Half-Baked Communism: “To each according to his need”?

Part II: India’s Right Road Forward Now: Some Thoughtful Analysis for Grown Ups

5. Transcending a Left-Right/Congress-BJP Divide in Indian Politics

6. Budgeting Military & Foreign Policy

7. Solving the Kashmir Problem & Relations with Pakistan

8. Dealing with Communist China

9. Towards Coherence in Public Accounting, Public Finance & Public Decision-Making

10. India’s Money: Towards Currency Integrity at Home & Abroad

Part I: Facts vs Fiction, Flattery, Falsification, etc

1. Problem

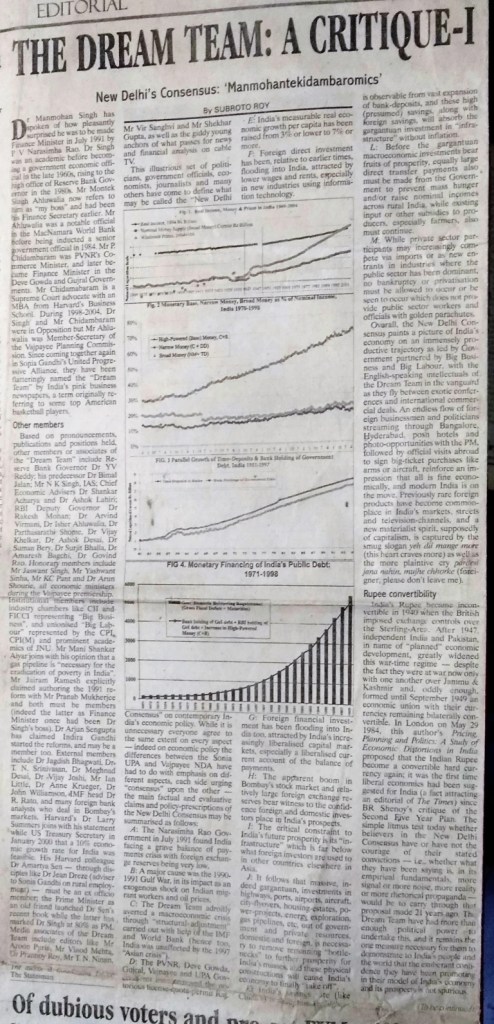

Arvind Panagariya says in the Times of India of 27 July 2013

“…if in 1991 India embraced many of the Track-I reforms, writings by Sen played no role in it… The intellectual origins of the reforms are to be found instead in the writings of Bhagwati, both solely and jointly with Padma Desai and T N Srinivasan….”

Now Amartya Sen has not claimed involvement in the 1991 economic reforms so we are left with Panagariya claiming

“The intellectual origins of the reforms are to be found instead in the writings of Bhagwati…”

Should we suppose Professor Panagariya’s master and co-author Jagdish Bhagwati himself substantially believes and claims the same? Three recent statements from Professor Bhagwati suffice by way of evidence:

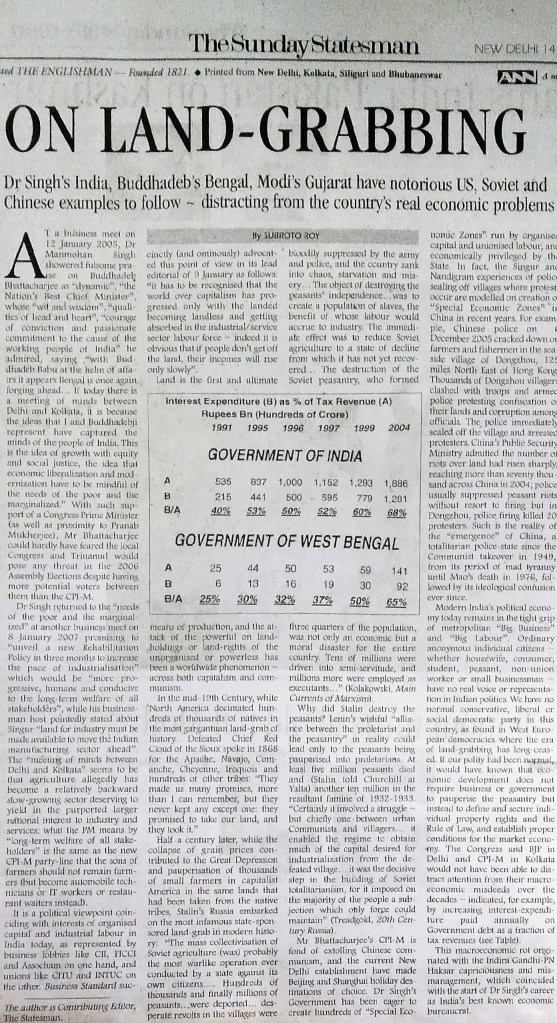

(A) Bhagwati said to parliamentarians in the Lok Sabha on 2 December 2010 about the pre-1991 situation:

“This policy framework had been questioned, and its total overhaul advocated, by me and Padma Desai in writings through the late 1960s which culminated in our book, India: Planning for Industrialization (Oxford University Press: 1970) with a huge blowback at the time from virtually all the other leading economists and policymakers who were unable to think outside the box. In the end, our views prevailed and the changes which would transform the economy began, after an external payments crisis in 1991, under the forceful leadership of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh who was the Finance Minister at the time….”

(B) Bhagwati said to Economic Times on 28 July 2013:

“When finance minister Manmohan Singh was in New York in 1992, he had a lunch for many big CEOs whom he was trying to seduce to come to India. He also invited me and my wife, Padma Desai, to the lunch. As we came in, the FM introduced us to the invitees and said: ‘These friends of mine wrote almost a quarter century ago [India: Planning for Industrialisation was published in 1970 by Oxford] recommending all the reforms we are now undertaking. If we had accepted the advice then, we would not be having this lunch as you would already be in India’.”

(C) And Bhagwati said in Business Standard of 9 August 2013:

“… I was among the intellectual pioneers of the Track I reforms that transformed our economy and reduced poverty, and witness to that is provided by the Prime Minister’s many pronouncements and by noted economists like Deena Khatkhate.. I believe no one has accused Mr. Sen of being the intellectual father of these reforms. So, the fact is that this huge event in the economic life of India passed him by…”

From these pronouncements it seems fair to conclude Professors Bhagwati and Panagariya are claiming Bhagwati has been the principal author of “the intellectual origins” of India’s 1991 reforms, has been their “intellectual father” or at the very least has been “among the intellectual pioneers” of the reform (“among” his own collaborators and friends, since none else is mentioned). Bhagwati has said too his friend Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister participated in the process while quoting Manmohan as having said Bhagwati was the principal author.

Bhagwati’s opponent in current debate, Amartya Sen, has been in agreement with him that Manmohan, their common friend during college days at Cambridge in the 1950s, was a principal originating the 1991 reforms, saying to Forbes in 2006:

“When Manmohan Singh came to office in the early 1990s as the newly appointed finance minister, in a government led by the Congress Party, he knew these problems well enough, as someone who had been strongly involved in government administration for a long time.”

In my experience, such sorts of claims, even in their weakest form, have been, at best, scientifically sloppy and unscholarly, at worst mendacious suppressio veri/suggestio falsi, and in between these best and worst interpretations, examples of academic self-delusion and mutual flattery. We shall see Bhagwati’s opponent, Amartya Sen, has denied academic paternity of recent policies he has spawned while appearing to claim academic paternity of things he has not! Everyone may have reasonably expected greater self-knowledge, wisdom and scholarly values of such eminent academics. Their current spat has instead seemed to reveal something rather dismal and self-serving.

You can decide for yourself where the truth, ever such an elusive and fragile thing, happens to be and what is best done about it. Here is some evidence.

2. Rajiv Gandhi, Siddhartha Shankar Ray, Milton Friedman & Myself

Professor Arvind Panagariya is evidently an American economics professor of Indian national origin who holds the Jagdish Bhagwati Chair of Indian Political Economy at Columbia University. I am afraid I had not known his name until he mentioned my name in Economic Times of 24 October 2001. He said

In mentioning the volume “edited by Subroto Roy and William E James”, Professor Panagariya did not appear to find the normal scientific civility to identify our work by name, date or publisher. So here that is now:

This was a book published in 1992 by the late Tejeshwar Singh for Sage. It resulted from the University of Hawaii Manoa perestroika-for-India project, that I and Ted James created and led between 1986 and 1992/93. (Yes, Hawaii — not Stanford, Harvard, Yale, Columbia or even Penn, whose India-policy programs were Johnny-come-latelies a decade or more later…) There is a sister-volume too on Pakistan, created by a parallel project Ted and I had led at the same time (both now in pdf):

In 2004 from Britain, I wrote to the 9/11 Commission saying if our plan to study Afghanistan after India and Pakistan had not been thwarted by malign local forces among our sponsors themselves, we, a decade before the September 11 2001 attacks on the USA, may just have come up with a pre-emptive academic analysis. It was not to be.

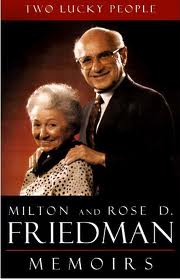

Milton Friedman’s chapter that we published for the first time was a memorandum he wrote in November 1955 for the Government of India which the GoI had effectively suppressed. I came to know of it while a doctoral student at Cambridge under Frank Hahn, when at a conference at Oxford about 1979-1980, Peter Tamas Bauer sat me down beside him and told me the story. Later in Blacksburg about 1981, N. Georgescu-Roegen on a visit from Vanderbilt University told me the same thing. Specifically, Georgescu-Roegen told me that leading Indian academics had almost insulted Milton in public which Milton had borne gamely; that after Milton had given a talk in Delhi to VKRV Rao’s graduate-students, a talk Georgescu-Roegen had been present at, VKRV Rao had addressed the students and told them in all seriousness “You have heard what Professor Friedman has to say, if you repeat what he has said in your exams, you will fail”.

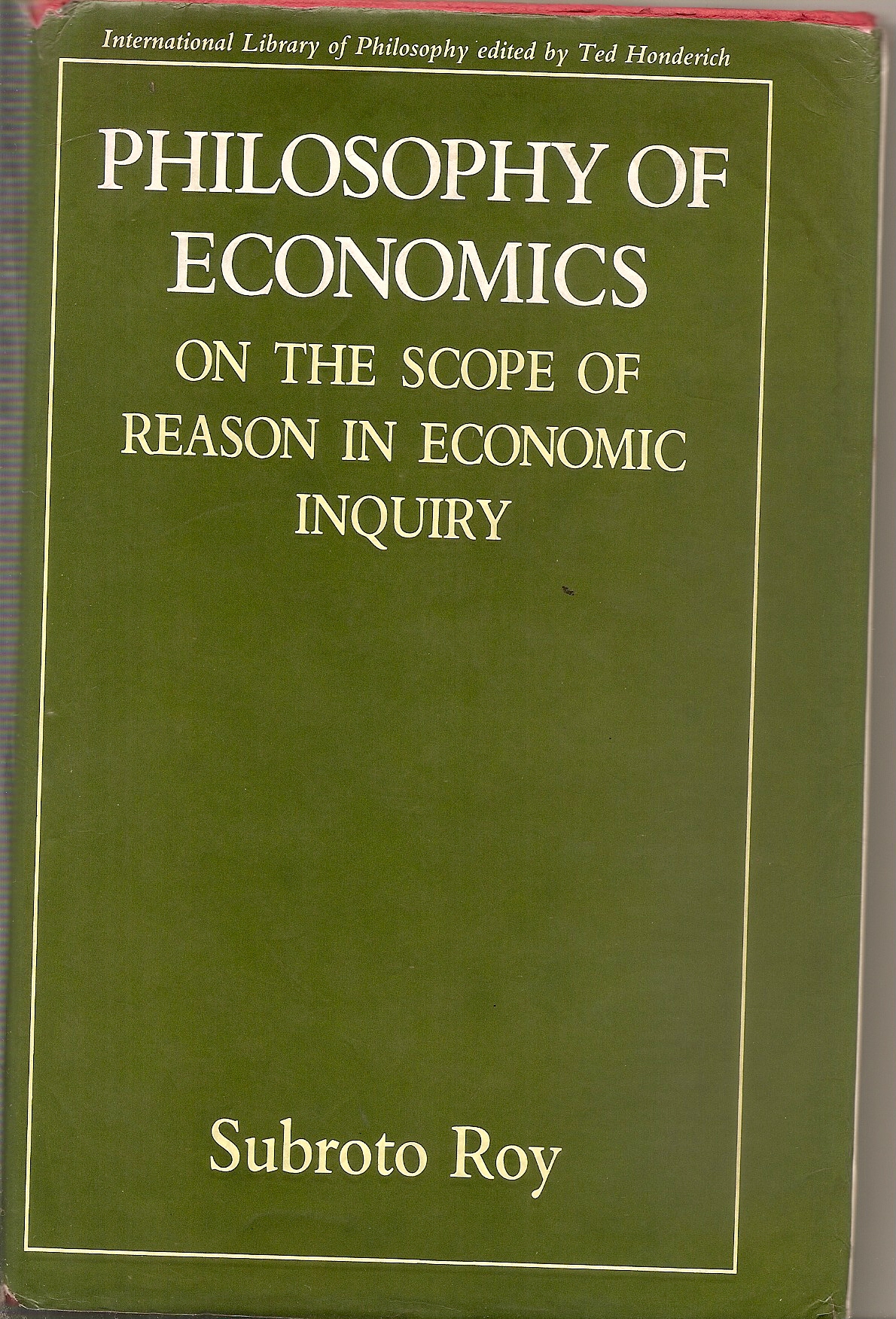

In 1981-1982 my doctoral thesis emerged, titled “On liberty & economic growth: preface to a philosophy for India”,

My late great master in economic theory, Frank Hahn (1925-2013), found what I had written to be a “good thesis” bringing “a good knowledge of economics and of philosophy to bear on the literature on economic planning”, saying I had shown “a good knowledge of economic theory” and my “critique of Development Economics was powerful not only on methodological but also on economic theory grounds”.

I myself said about it decades later “My original doctoral topic in 1976 ‘A monetary theory for India’ had to be altered not only due to paucity of monetary data at the time but because the problems of India’s political economy and allocation of resources in the real economy were far more pressing. The thesis that emerged in 1982 … was a full frontal assault from the point of view of microeconomic theory on the “development planning” to which everyone routinely declared their fidelity, from New Delhi’s bureaucrats and Oxford’s “development” school to McNamara’s World Bank with its Indian staffers. Frank Hahn protected my inchoate liberal arguments for India; and when no internal examiner could be found, Cambridge showed its greatness by appointing two externals, Bliss at Oxford and Hutchison at Birmingham, both Cambridge men. “Economic Theory and Development Economics” was presented to the American Economic Association in December 1982 in company of Solow, Chenery, Streeten, and other eminences…” How I landed on that eminent AEA panel in December 1982 was because its convener Professor George Rosen of the University of Illinois recruited me overnight — as a replacement for Jagdish Bhagwati, who had had to return to India suddenly because of a parental death. The results were published in 1983 in World Development.

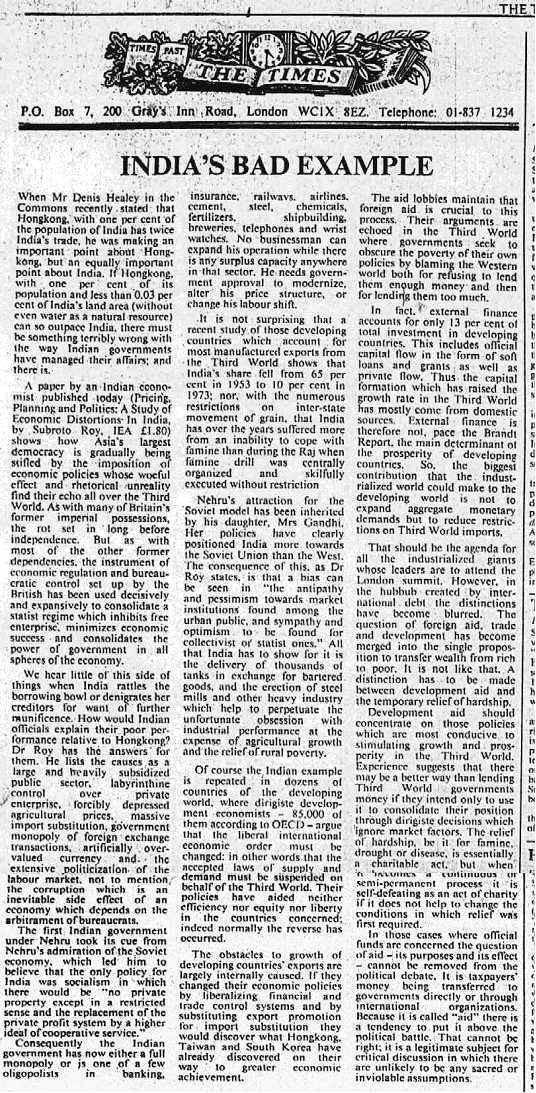

Soon afterwards, London’s Institute of Economic Affairs published Pricing, Planning and Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India. This slim work (now in pdf) was the first classical liberal critique of post-Mahalonobis Indian economic thought since BR Shenoy’s original criticism decades earlier. It became the subject of The Times’ lead editorial on its day of publication 29 May 1984 — provoking the Indian High Commission in London to send copies to the Finance Ministry in Delhi where it apparently caused a stir, or so I was told years later by Amaresh Bagchi who was a recipient of it at the Ministry.

The Times had said

“When Mr. Dennis Healey in the Commons recently stated that Hongkong, with one per cent of the population of India has twice India’s trade, he was making an important point about Hongkong but an equally important point about India. If Hongkong with one per cent of its population and less than 0.03 per cert of India’s land area (without even water as a natural resource) can so outpace India, there must be something terribly wrong with the way Indian governments have managed their affairs, and there is. A paper by an Indian economist published today (Pricing, Planning and Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India by Subroto Roy, IEA £1.80) shows how Asia’s largest democracy is gradually being stifled by the imposition of economic policies whose woeful effect and rhetorical unreality find their echo all over the Third World. As with many of Britain’s former imperial possessions, the rot set in long before independence. But as with most of the other former dependencies, the instrument of economic regulation and bureaucratic control set up by the British has been used decisively and expansively to consolidate a statist regime which inhibits free enterprise, minimizes economic success and consolidates the power of government in all spheres of the economy. We hear little of this side of things when India rattles the borrowing bowl or denigrates her creditors for want of further munificence. How could Indian officials explain their poor performance relative to Hongkong? Dr Roy has the answers for them. He lists the causes as a large and heavily subsidized public sector, labyrinthine control over private enterprise, forcibly depressed agricultural prices, massive import substitution, government monopoly of foreign exchange transactions, artificially overvalued currency and the extensive politicization of the labour market, not to mention the corruption which is an inevitable side effect of an economy which depends on the arbitrament of bureaucrats. The first Indian government under Nehru took its cue from Nehru’s admiration of the Soviet economy, which led him to believe that the only policy for India was socialism in which there would be “no private property except in a restricted sense and the replacement of the private profit system by a higher ideal of cooperative service.” Consequently, the Indian government has now either a full monopoly or is one of a few oligipolists in banking, insurance, railways, airlines, cement, steel, chemicals, fertilizers, ship-building, breweries, telephones and wrist-watches. No businessman can expand his operation while there is any surplus capacity anywhere in that sector. He needs government approval to modernize, alter his price-structure, or change his labour shift. It is not surprising that a recent study of those developing countries which account for most manufactured exports from the Third World shows that India’s share fell from 65 percent in 1953 to 10 per cent in 1973; nor, with the numerous restrictions on inter-state movement of grains, that India has over the years suffered more from an inability to cope with famine than during the Raj when famine drill was centrally organized and skillfully executed without restriction. Nehru’s attraction for the Soviet model has been inherited by his daughter, Mrs. Gandhi. Her policies have clearly positioned India more towards the Soviet Union than the West. The consequences of this, as Dr Roy states, is that a bias can be seen in “the antipathy and pessimism towards market institutions found among the urban public, and sympathy and optimism to be found for collectivist or statist ones.” All that India has to show for it is the delivery of thousands of tanks in exchange for bartered goods, and the erection of steel mills and other heavy industry which help to perpetuate the unfortunate obsession with industrial performance at the expense of agricultural growth and the relief of rural poverty.”…..

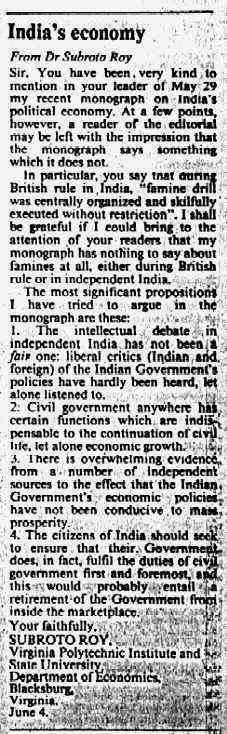

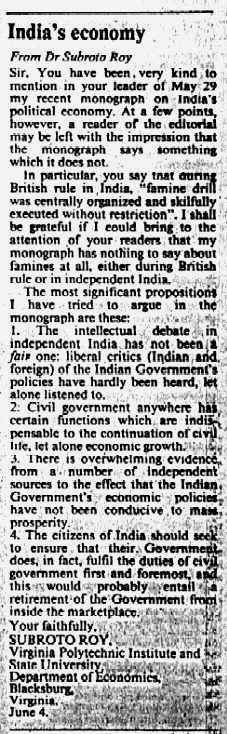

I felt there were inaccuracies in this and so replied dated 4 June which The Times published on 16 June 1984:

Milton and I met for the first time in the Fall of 1984 at the Mont Pelerin Society meetings at Cambridge when I gave him a copy of the IEA monograph, which he came to think extremely well of. I told him I had heard of his 1955 document and asked him for it; he sent me the original blue/purple version of this soon thereafter.

[That original document was, incidentally, in my professorial office among all my books, papers, theses and other academic items including my gown when I was attacked in 2003 by a corrupt gang at IIT Kharagpur — all yet to be returned to me by IIT despite a High Court order during my present ongoing battle against corruption there over a USD 1.9 million scam !… Without having ever wished to, I have had to battle India’s notorious corruption first hand for a decade!]

I published Milton’s document for the first time on 21 May 1989 at the conference of the Hawaii project over the loud objection of assorted leftists…

Amartya Sen, Jagdish Bhagwati, Manmohan Singh or any of their acolytes will not be seen in this group photograph dated 21 May 1989 at the UH President’s House, because they were not there. The Government of India was represented by the Ambassador to Washington, PK Kaul, as well as the Consul General in San Francisco, KS Rana (later Ambassador to Germany), besides the founding head of ICRIER who had invited himself.

Manmohan Singh was not there as he precisely represented the Indian economic policy establishment I had been determined to reform! In any case, he had left India about 1987 on his last assignment before retirement, with Julius Nyerere of Tanzania relating to the “South-South Commission”.

I have said over more than a half dozen years now that there is no evidence whatsoever of Manmohan Singh having been a liberal economist in any sense of that word at any time before 1991, and scant evidence that he originated any liberal economic ideas since. The widespread worldwide notion that he is to be credited for originating a sudden transformation of India from a path of pseudo-socialism to one of pseudo-liberalism has been without basis in evidence — almost entirely a political fiction, though an explicable one and one which has served, as such political fictions do, the purposes of those who invent them.

Jagdish Bhagwati and Amartya Sen were in their mid 50s and were two of the three senior-most Indians in US academic economics at the time. I and Ted James, both in our 30s, decided to invite both Bhagwati and Sen to the Hawaii project-conference as distinguished guests but to do so somewhat insincerely late in the day, predicting they would decline, which is what they did, yet they had come to be formally informed of what we were doing. We had a very serious attitude that was inspired a bit, I might say, by Oppenheimer’s secret “Manhattan project” and we wanted neither press-publicity nor anyone to become the star who ended up hogging the microphone or the limelight.

Besides, and most important of all, neither Bhagwati nor Sen had done work in the areas we were centrally interested in, namely, India’s macroeconomic and foreign trade framework and fiscal and monetary policies.

Bhagwati, after his excellent 1970 work with Padma Desai for the OECD on Indian industry and trade, also co-authored with TN Srinivasan a fine 1975 volume for the NBER Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: India.

TN Srinivasan was the third of the three senior-most Indian economists at the time in US academia; his work made us want to invite him as one of our main economic authors, and we charged him with writing the excellent chapter in Foundations that he came to do titled “Planning and Foreign Trade Reconsidered”.

The other main economist author we had hoped for was Sukhamoy Chakravarty from Delhi University and the Government of India’s Planning Commission, whom I had known since 1977 when I had been given his office at the Delhi School of Economics as a Visiting Assistant Professor while he was on sabbatical; despite my pleading he would not come due to ill health; he strongly recommended C Rangarajan, telling me Rangarajan had been the main author with him of the crucial 1985 RBI report on monetary policy; and he signed and gave me his last personal copy of that report dating it 14 July 1987. Rangarajan said he could not come and recommended the head of the NIPFP, Amaresh Bagchi, promising to write jointly with him the chapter on monetary policy and public finance.

Along with Milton Friedman’s suppressed 1955 memorandum which I was publishing for the first time in 1989, TN Srinivasan and Amaresh Bagchi authored the three main economic policy chapters that we felt we wanted.

Other chapters we commissioned had to do with the state of governance (James Manor), federalism (Bhagwan Dua), Punjab and similar problems (PR Brass), agriculture (K Subbarao, as proposed by CH Hanumantha Rao), health (Anil Deolalikar, through open advertisement), and a historical assessment of the roots of economic policy (BR Tomlinson, as proposed by Anil Seal). On the vital subject of education we failed to agree with the expert we wanted very much (JBG Tilak, as proposed by George Psacharopolous) and so we had to cover the subject cursorily in our introduction mentioning his work. And decades later, I apologised to Professor Dietmar Rothermund of Heidelberg University for having been so blinkered in the Anglo-American tradition at the time as to not having obtained his participation in the project.

[The sister-volume we commissioned in parallel on Pakistan’s political economy had among its authors Francis Robinson, Akbar Ahmed, Shirin Tahir-Kehli, Robert La Porte, Shahid Javed Burki, Mohsin Khan, Mahmood Hasan Khan, Naved Hamid, John Adams and Shahrukh Khan; this book came to be published in Pakistan in 1993 to good reviews but apparently was then lost by its publisher and is yet to be found; the military and religious clergy had been deliberately not invited by us though the name of Pervez Musharraf had I think arisen, and the military and religious clergy in fact came to rule the roost through the 1990s in Pakistan; the volume, two decades old, takes on fresh relevance with the new civilian governments of recent years.] [Postscript 27 November 2015: See my strident critique at Twitter of KM Kasuri, P Musharraf et al e.g. at https://independentindian.com/2011/11/22/pakistans-point-of-view-or-points-of-view-on-kashmir-my-as-yet-undelivered-lahore-lecture-part-i/ passing off ideas they have taken from this volume without acknowledgement, ideas which have in any case become defunct to their author, myself.]

Milton himself said this about his experience with me in his memoirs:

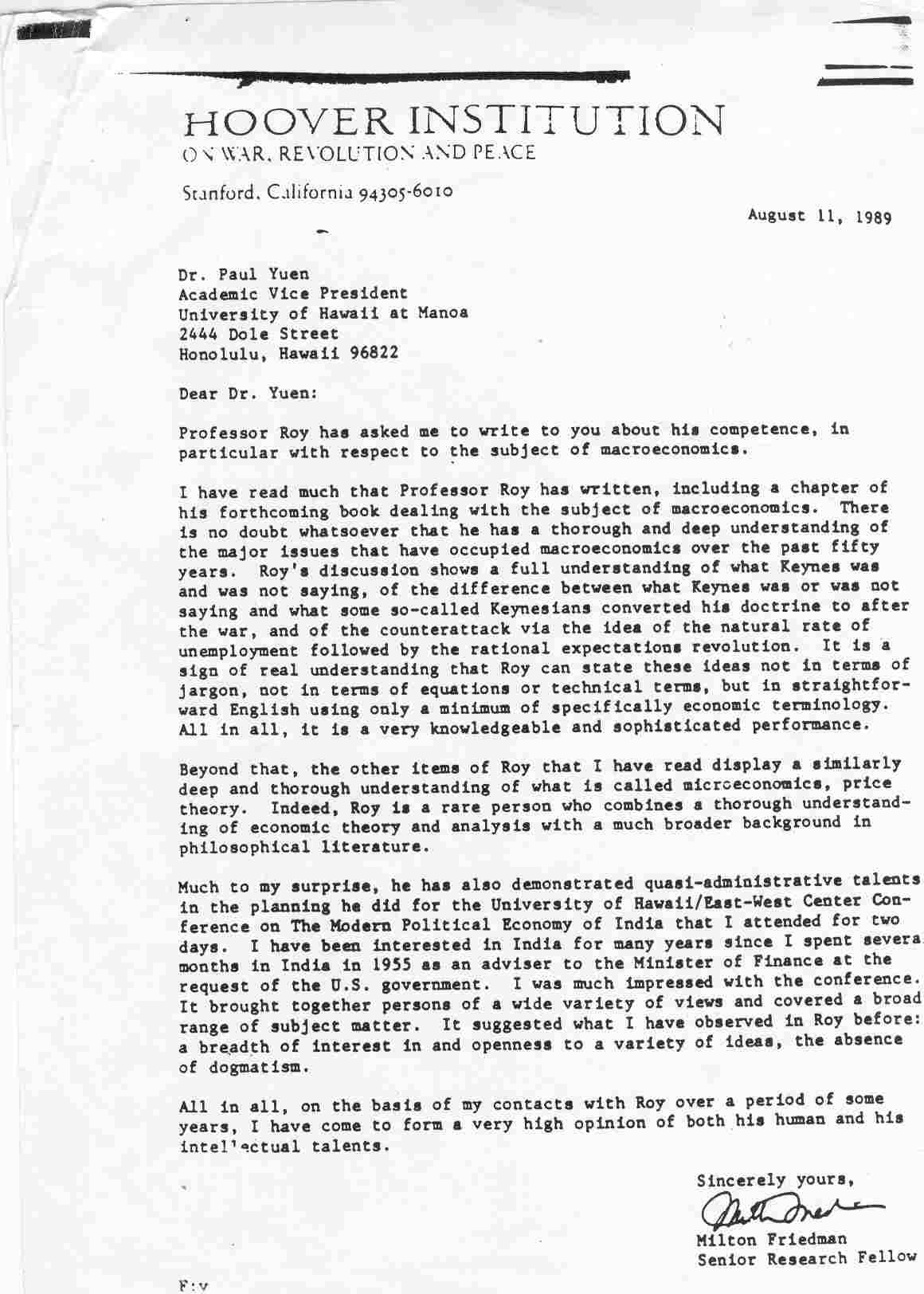

And Milton wrote on my behalf when I came to be attacked, being Indian, at the very University that had sponsored us:

My obituary notice at his passing in 2006 said: “My association with Milton has been the zenith of my engagement with academic economics…. I was a doctoral student of his bitter enemy yet for over two decades he not only treated me with unfailing courtesy and affection, he supported me in lonely righteous battles: doing for me what he said he had never done before, which was to stand as an expert witness in a United States Federal Court. I will miss him much though I know that he, as a man of reason, would not have wished me to….”

In August 1990 in Delhi I came to tell Siddhartha Shankar Ray about the unpublished India-manuscript resulting from the Hawaii project that was in my possession as it headed to its publisher.

Ray was a family-friend whose maternal grandfather CR Das led the Congress Party before MK Gandhi and had been a friend and colleague of my great grandfather SN Roy in Bengal’s politics in the 1920s; Ray had also consented to stand on my behalf as Senior Counsel in a matter in the Supreme Court of India.

Ray was involved in daily political parlays at his Delhi home with other Congress Party personages led by PV Narasimha Rao. These senior regional figures seemed to me to be keeping their national leader, Rajiv Gandhi, aloof in splendid isolation at 10 Jan Path.

Ray told me he and his wife had been in London in May 1984 on the day The Times had written its lead editorial on my work and they had seen it with excitement. Upon hearing of the Hawaii project and the manuscript I had with me, Ray immediately insisted of his own accord that I must meet Rajiv Gandhi, and that he would be arranging a meeting.

Hence it came to be a month later that a copy of the manuscript of the completed Hawaii project was be given by my hand on 18 September 1990 to Rajiv Gandhi, then Leader of the Opposition and Congress President, an encounter I have quite fully described elsewhere. I offered to get a copy to the PM, VP Singh, too but a key aide of his showed no interest in receiving it.

Rajiv made me a senior adviser, and I have claimed principal authorship of the 22 March 1991 draft of the Congress manifesto that actually shook and changed the political thinking of the Congress on economic matters in the direction Rajiv had desired and as I had advised him at our initial 18 September 1990 meeting.

“… He began by talking about how important he felt panchayati raj was, and said he had been on the verge of passing major legislation on it but then lost the election. He asked me if I could spend some time thinking about it, and that he would get the papers sent to me. I said I would and remarked panchayati raj might be seen as decentralized provision of public goods, and gave the economist’s definition of public goods as those essential for the functioning of the market economy, like the Rule of Law, roads, fresh water, and sanitation, but which were unlikely to appear through competitive forces.

I distinguished between federal, state and local levels and said many of the most significant public goods were best provided locally. Rajiv had not heard the term “public goods” before, and he beamed a smile and his eyes lit up as he voiced the words slowly, seeming to like the concept immensely. It occurred to me he had been by choice a pilot of commercial aircraft. Now he seemed intrigued to find there could be systematic ways of thinking about navigating a country’s governance by common pursuit of reasonable judgement. I said the public sector’s wastefulness had drained scarce resources that should have gone instead to provide public goods. Since the public sector was owned by the public, it could be privatised by giving away its shares to the public, preferably to panchayats of the poorest villages. The shares would become tradable, drawing out black money, and inducing a historic redistribution of wealth while at the same time achieving greater efficiency by transferring the public sector to private hands. Rajiv seemed to like that idea too, and said he tried to follow a maxim of Indira Gandhi’s that every policy should be seen in terms of how it affected the common man. I wryly said the common man often spent away his money on alcohol, to which he said at once it might be better to think of the common woman instead. (This remark of Rajiv’s may have influenced the “aam admi” slogan of the 2004 election, as all Congress Lok Sabha MPs of the previous Parliament came to receive a previous version of the present narrative.)

Our project had identified the Congress’s lack of internal elections as a problem; when I raised it, Rajiv spoke of how he, as Congress President, had been trying to tackle the issue of bogus electoral rolls. I said the judiciary seemed to be in a mess due to the backlog of cases; many of which seemed related to land or rent control, and it may be risky to move towards a free economy without a properly functioning judicial system or at least a viable system of contractual enforcement. I said a lot of problems which should be handled by the law in the courts in India were instead getting politicised and decided on the streets. Rajiv had seen the problems of the judiciary and said he had good relations with the Chief Justice’s office, which could be put to use to improve the working of the judiciary.

The project had worked on Pakistan as well, and I went on to say we should solve the problem with Pakistan in a definitive manner. Rajiv spoke of how close his government had been in 1988 to a mutual withdrawal from Siachen. But Zia-ul-Haq was then killed and it became more difficult to implement the same thing with Benazir Bhutto, because, he said, as a democrat, she was playing to anti-Indian sentiments while he had found it somewhat easier to deal with the military. I pressed him on the long-term future relationship between the countries and he agreed a common market was the only real long-term solution. I wondered if he could find himself in a position to make a bold move like offering to go to Pakistan and addressing their Parliament to break the impasse. He did not say anything but seemed to think about the idea. Rajiv mentioned a recent Time magazine cover of Indian naval potential, which had caused an excessive stir in Delhi. He then talked about his visit to China, which seemed to him an important step towards normalization. He said he had not seen (or been shown) any absolute poverty in China of the sort we have in India. He talked about the Gulf situation, saying he did not disagree with the embargo of Iraq except he wished the ships enforcing the embargo had been under the U.N. flag. The meeting seemed to go on and on, and I was embarrassed at perhaps having taken too much time and that he was being too polite to get me to go. V. George had interrupted with news that Sheila Dixit (as I recall) had just been arrested by the U. P. Government, and there were evidently people waiting. Just before we finally stood up I expressed a hope that he was looking to the future of India with an eye to a modern political and economic agenda for the next election, rather than getting bogged down with domestic political events of the moment. That was the kind of hopefulness that had attracted many of my generation in 1985. I said I would happily work in any way to help define a long-term agenda. His eyes lit up and as we shook hands to say goodbye, he said he would be in touch with me again…. The next day I was called and asked to stay in Delhi for a few days, as Mr. Gandhi wanted me to meet some people…..

… That night Krishna Rao dropped me at Tughlak Road where I used to stay with friends. In the car I told him, as he was a military man with heavy security cover for himself as a former Governor of J&K, that it seemed to me Rajiv’s security was being unprofessionally handled, that he was vulnerable to a professional assassin. Krishna Rao asked me if I had seen anything specific by way of vulnerability. With John Kennedy and De Gaulle in mind, I said I feared Rajiv was open to a long-distance sniper, especially when he was on his campaign trips around the country. This was one of several attempts I made since October 1990 to convey my clear impression to whomever I thought might have an effect that Rajiv seemed to me extremely vulnerable. Rajiv had been on sadhbhavana journeys, back and forth into and out of Delhi. I had heard he was fed up with his security apparatus, and I was not surprised given it seemed at the time rather bureaucratized. It would not have been appropriate for me to tell him directly that he seemed to me to be vulnerable, since I was a newcomer and a complete amateur about security issues, and besides if he agreed he might seem to himself to be cowardly or have to get even closer to his security apparatus. Instead I pressed the subject relentlessly with whomever I could. I suggested specifically two things: (a) that the system in place at Rajiv’s residence and on his itineraries be tested, preferably by some internationally recognized specialists in counter-terrorism; (b) that Rajiv be encouraged to announce a shadow-cabinet. The first would increase the cost of terrorism, the second would reduce the potential political benefit expected by terrorists out to kill him. On the former, it was pleaded that security was a matter being run by the V. P. Singh and then Chandrashekhar Governments at the time. On the latter, it was said that appointing a shadow cabinet might give the appointees the wrong idea, and lead to a challenge to Rajiv’s leadership. This seemed to me wrong, as there was nothing to fear from healthy internal contests for power so long as they were conducted in a structured democratic framework. I pressed to know how public Rajiv’s itinerary was when he travelled. I was told it was known to everyone and that was the only way it could be since Rajiv wanted to be close to the people waiting to see him and had been criticized for being too aloof. This seemed to me totally wrong and I suggested that if Rajiv wanted to be seen as meeting the crowds waiting for him then that should be done by planning to make random stops on the road that his entourage would take. This would at least add some confusion to the planning of potential terrorists out to kill him. When I pressed relentlessly, it was said I should probably speak to “Madame”, i.e. to Mrs. Rajiv Gandhi. That seemed to me highly inappropriate, as I could not be said to be known to her and I should not want to unduly concern her in the event it was I who was completely wrong in my assessment of the danger. The response that it was not in Congress’s hands, that it was the responsibility of the VP Singh and later the Chandrashekhar Governments, seemed to me completely irrelevant since Congress in its own interests had a grave responsibility to protect Rajiv Gandhi irrespective of what the Government’s security people were doing or not doing. Rajiv was at the apex of the power structure of the party, and a key symbol of secularism and progress for the entire country. Losing him would be quite irreparable to the party and the country. It shocked me that the assumption was not being made that there were almost certainly professional killers actively out to kill Rajiv Gandhi — this loving family man and hapless pilot of India’s ship of state who did not seem to have wished to make enemies among India’s terrorists but whom the fates had conspired to make a target. The most bizarre and frustrating response I got from several respondents was that I should not mention the matter at all as otherwise the threat would become enlarged and the prospect made more likely! This I later realized was a primitive superstitious response of the same sort as wearing amulets and believing in Ptolemaic astrological charts that assume the Sun goes around the Earth — centuries after Kepler and Copernicus. Perhaps the entry of scientific causality and rationality is where we must begin in the reform of India’s governance and economy. What was especially repugnant after Rajiv’s assassination was to hear it said by his enemies that it marked an end to “dynastic” politics in India. This struck me as being devoid of all sense because the unanswerable reason for protecting Rajiv Gandhi was that we in India, if we are to have any pretensions at all to being a civilized and open democratic society, cannot tolerate terrorism and assassination as means of political change. Either we are constitutional democrats willing to fight for the privileges of a liberal social order, or ours is truly a primitive and savage anarchy concealed beneath a veneer of fake Westernization….. Proceedings began when Rajiv arrived. This elite audience mobbed him just as the farmers had mobbed him earlier. He saw me and beamed a smile in recognition, and I smiled back but made no attempt to draw near him in the crush. He gave a short very apt speech on the role the United Nations might have in the new post-Gulf War world. Then he launched the book, and left for an investiture at Rashtrapati Bhavan. We waited for our meeting with him, which finally happened in the afternoon. Rajiv was plainly at the point of exhaustion and still hard-pressed for time. He seemed pleased to see me and apologized for not talking in the morning. Regarding the March 22 draft, he said he had not read it but that he would be doing so. He said he expected the central focus of the manifesto to be on economic reform, and an economic point of view in foreign policy, and in addition an emphasis on justice and the law courts. I remembered our September 18 conversation and had tried to put in justice and the courts into our draft but had been over-ruled by others. I now said the social returns of investment in the judiciary were high but was drowned out again. Rajiv was clearly agitated that day by the BJP and blurted out he did not really feel he understood what on earth they were on about. He said about his own family, “We’re not religious or anything like that, we don’t pray every day.” I felt again what I had felt before, that here was a tragic hero of India who had not really wished to be more than a happy family man until he reluctantly was made into a national leader against his will. We were with him for an hour or so. As we were leaving, he said quickly at the end of the meeting he wished to see me on my own and would be arranging a meeting. One of our group was staying back to ask him a favour. Just before we left, I managed to say to him what I felt was imperative: “The Iraq situation isn’t as it seems, it’s a lot deeper than it’s been made out to be.” He looked at me with a serious look and said “Yes I know, I know.” It was decided Pitroda would be in touch with each of us in the next 24 hours. During this time Narasimha Rao’s manifesto committee would read the draft and any questions they had would be sent to us. We were supposed to be on call for 24 hours. The call never came. Given the near total lack of system and organization I had seen over the months, I was not surprised. Krishna Rao and I waited another 48 hours, and then each of us left Delhi. Before going I dropped by to see Krishnamurty, and we talked at length. He talked especially about the lack of the idea of teamwork in India. Krishnamurty said he had read everything I had written for the group and learned a lot. I said that managing the economic reform would be a critical job and the difference between success and failure was thin….”

“… I got the afternoon train to Calcutta and before long left for America to bring my son home for his summer holidays with me. In Singapore, the news suddenly said Rajiv Gandhi had been killed. All India wept. What killed him was not merely a singular act of criminal terrorism, but the system of humbug, incompetence and sycophancy that surrounds politics in India and elsewhere. I was numbed by rage and sorrow, and did not return to Delhi….”

In December 1991, I visited Rajiv’s widow at 10 Jan Path to express my condolences, the only time I have met her, and I gave her for her records a taped copy of Rajiv’s long-distance telephone conversations with me during the Gulf War earlier that year. She seemed an extremely shy taciturn figure in deep mourning, and I do not think the little I said to her about her late husband’s relationship with me was comprehended. Nor was it the time or place for more to be said.

In September 1993, at a special luncheon at the Indian Ambassador’s Residence in Washington, Siddhartha Shankar Ray, then the Ambassador to Washington, pointed at me and declared to Manmohan Singh, then Finance Minister, in presence of Manmohan’s key aides accompanying him including MS Ahluwalia, NK Singh, C Rangarajan and others,

“Congress manifesto was written on his computer”.

This was accurate enough to the extent that the 22 March 1991 draft as asked for by Rajiv and that came to explicitly affect policy had been and remains on my then-new NEC laptop.

At the Ambassador’s luncheon, I gave Manmohan Singh a copy of the Foundations book as a gift. My father who knew him in the early 1970s through MG Kaul, ICS, had sent him a copy of my 1984 IEA monograph which Manmohan had acknowledged. And back in 1973, he had visited our then-home at 14 Rue Eugene Manuel in Paris to advise me about economics at my father’s request, and he and I had ended up in a fierce private debate for about forty minutes over the demerits (as I saw them) and merits (as he saw them) of the Soviet influence on Indian economic policy-making. But in 1993 we had both forgotten the 1973 meeting.

In May 2002, the Congress passed an official party resolution moved by Digvijay Singh in presence of PV Narasimha Rao and Manmohan Singh that the 1991 reforms had originated with Rajiv Gandhi and not with either Narasimha Rao or Manmohan; no one dissented. It was intended to flatter Sonia Gandhi as the Congress President, but there was truth in it too which all Congress MPs of the 13th Lok Sabha had come to know in a publication of mine they had received from me at IIT Kharagpur where since 1996 I had become Professor.

Manmohan Singh himself, to his credit, has not at any point, except once during his failed Lok Sabha bid, claimed the reforms as his own invention and has said always he had followed what his Prime Minister had told him. However, he has not been averse to being attributed with all the credit by his flatterers, by the media, by businessmen and many many others around the world, and certainly he did not respond to Ambassador Siddhartha Shankar Ray telling him and his key aides how the Congress-led reform had come about through my work except to tell me at the 1993 luncheon that when Arjun Singh criticised the reforms in Cabinet, he, Manmohan, would mention the manifesto.

On 28 December 2009, Rajiv’s widow in an official Congress Party statement finally declared her late husband

“left his personal imprint on the (Congress) party’s manifesto of 1991.″

How Sonia Gandhi, who has never had pretensions to knowledge of economics or political economy or political science or governance or history, came to place Manmohan Singh as her prime ministerial candidate and the font of economic and political wisdom along with Pranab Mukherjee, when both men hardly had been favourites of her late husband, would be a story in its own right. And how Amartya Sen’s European-origin naturalised Indian co-author Jean Drèze later came to have policy influence from a different direction upon Sonia Gandhi, also a naturalised Indian of European origin, may be yet another story in its own right, perhaps best told by themselves.

I would surmise the same elderly behind-the-scenes figure, now in his late 80s, had a hand in setting up both sets of influences — directly in the first case (from back in 1990-1991), and indirectly in the second case (starting in 2004) . This was a man who in a November 2007 newspaper article literally erased my name and inserted that of Manmohan Singh as part of the group that Rajiv created on 25 September following his 18 September meeting with me! Reluctantly, I had to call this very elderly man a liar; he has not denied it and knows he has not been libeled.

One should never forget the two traditional powers interested in the subcontinent, Russia and Britain, have been never far from influence in Delhi. In 1990-1991 what worried vested bureaucratic and business interests and foreign powers through their friends and agents was that they could see change was coming to India but they wanted to be able to control it themselves to their advantage, which they then broadly proceeded to do over the next two decades. The foreign weapons’ contracts had to be preserved, as did other big-ticket imports that India ends up buying needlessly on credit it hardly has in world markets. There are similarities to what happened in Russia and Eastern Europe where many apparatchiks and fellow-travellers became freedom-loving liberals overnight; in the Indian case more than one badly compromised pro-USSR senior bureaucrat promptly exported his children and savings to America and wrapped themselves in the American flag.

The stubborn unalterable fact remains that Manmohan Singh was not physically present in India and was still with the Nyerere project on 18 September 1990 when I met Rajiv for the first time and gave him the unpublished results of the UH-Manoa project. This simple straightforward fact is something the Congress Party, given its own myths and self-deception and disinformation, has not been able to cope with in its recently published history. For myself, I have remained loyal to my memory of my encounter with Rajiv Gandhi, and my understanding of him. The Rajiv Gandhi I knew had been enthused by me in 1990-1991 carrying the UH-Manoa perestroika-for-India project that I had led since 1986, and he had loved my advice to him on 18 September 1990 that he needed to modernise the party by preparing a coherent agenda (as other successful reformers had done) while still in Opposition waiting for elections, and to base that agenda on commitments to improving the judiciary and rule of law, stopping the debauching of money, and focusing on the provision of public goods instead. Rajiv I am sure wanted a modern and modern-minded Congress — not one which depended on him let aside his family, but one which reduced that dependence and let him and his family alone.

As for Manmohan Singh being a liberal or liberalising economist, there is no evidence publicly available of that being so from his years before or during the Nyerere project, or after he returned and joined the Chandrashekhar PMO and the UGC until becoming, to his own surprise as he told Mark Tully, PV Narasimha Rao’s Finance Minister. Some of his actions qua Finance Minister were liberalising in nature but he did not originate any basic idea of a change in a liberal direction of economic policy, and he has, with utmost honesty honestly, not claimed otherwise. Innumerable flatterers and other self-interested parties have made out differently, creating what they have found to be a politically useful fiction; he has yet to deny them.

Siddhartha Shankar Ray and I met last in July 2009, when I gave him a copy of this 2005 volume I had created, which pleased him much.

I said to him Bengal’s public finances were in abysmal condition, calling for emergency measures financially, and that Mamata Banerjee seemed to me to be someone who knew how to and would dislodge the Communists from their entrenched misgovernance of decades but she did not seem quite aware that dislodging a bad government politically was not the same thing as knowing how to govern properly oneself. He, again of his own accord, said immediately,

“I will call her and her people to a meeting here so you can meet them and tell them that directly”.

It never transpired. In our last phone conversation I mentioned to him my plans of creating a Public Policy Institute — an idea he immediately and fully endorsed as being essential though adding “I can’t be part of it, I’m on my way out”.

“I’m on my way out”. That was Siddhartha Shankar Ray — always intelligent, always good-humoured, always public-spirited, always a great Indian, my only friend among politicians other than the late Rajiv Gandhi himself.

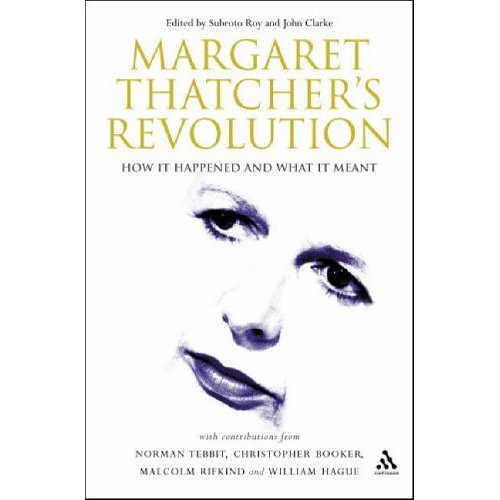

In March February 2010, my father and I called upon the new Bengal Governor, MK Narayanan and gave him a copy of the Thatcher volume for the Raj Bhavan Library; I told him the story about my encounter with Rajiv Gandhi thanks to Siddhartha Shankar Ray and its result; Narayanan within a few days made a visit to Ray’s hospital-bed, and when he emerged after several hours he made a statement, which in substance he repeated again when Ray died in November 2010:

“There are few people in post-Independence India who could equal his magnificent contribution to India’s growth and progress”.

To what facts did MK Narayanan, a former Intelligence Bureau chief, mean to refer with this extravagant praise of Ray? Was Narayanan referring to Ray’s politics for Indira Gandhi? To Ray’s Chief Ministership of Bengal? To Ray’s Governorship of Punjab? You will have to ask him but I doubt that was what he meant: I surmise Narayanan’s eulogy could only have resulted after he confirmed with Ray on his hospital-bed the story I had told him, and that he was referring to the economic and political results that followed for the country once Ray had introduced me in September 1990 to Rajiv Gandhi. But I say again, you will have to ask MK Narayanan himself what he and Ray talked about in hospital and what was the factual basis of Narayanan’s precise words of praise. To what facts exactly was MK Narayanan, former intelligence chief, meaning to refer when he stated Siddhartha Shankar Ray had made a “magnificent contribution to India’s growth and progress”?

3. Jagdish Bhagwati & Manmohan Singh? That just don’t fly!

Now returning to the apparent desire of Professor Panagariya, the Jagdish Bhagwati Professor of Indian Political Economy at Columbia, to attribute to Jagdish Bhagwati momentous change for the better in India as of 1991, even if Panagariya had not the scientific curiosity to look into our 1992 book titled Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s or into Milton Friedman’s own 1998 memoirs, we may have expected him to at least turn to his co-author and Columbia colleague, Jagdish Bhagwati himself, and ask, “Master, have you heard of this fellow Subroto Roy by any chance?”

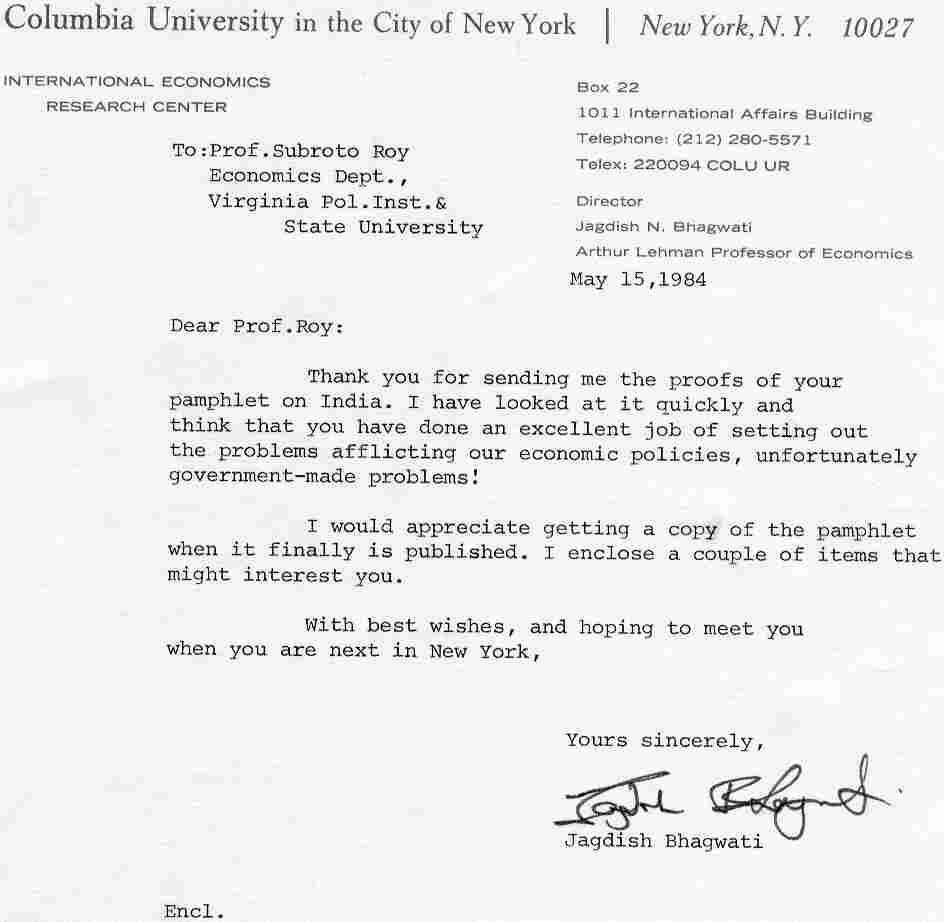

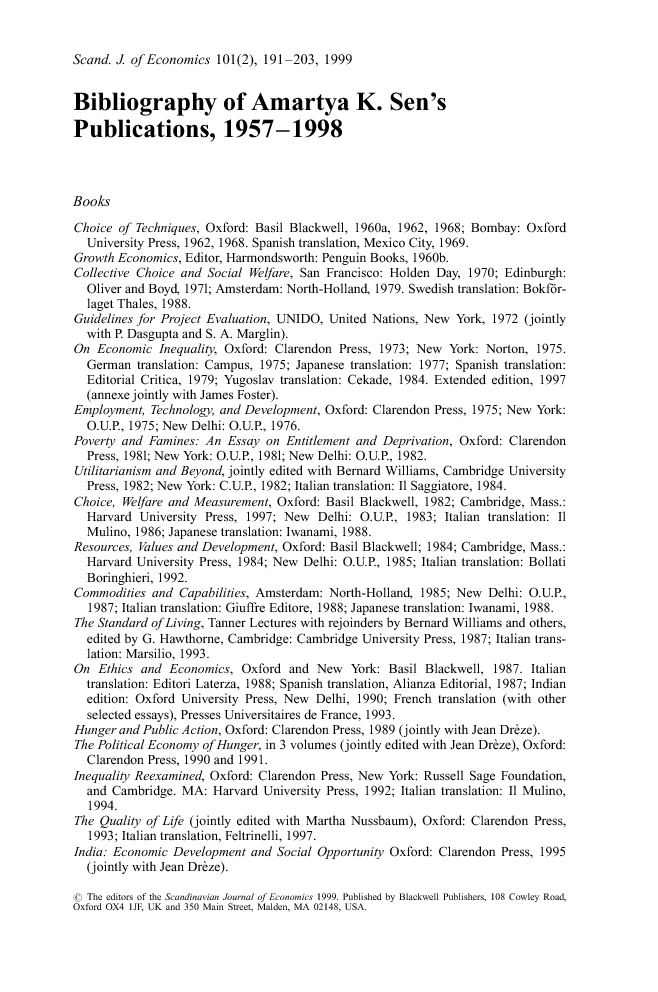

Jagdish would have had to say yes, since not only had he received a copy of the proofs of my 1984 IEA work Pricing, Planning and Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India, he was kind enough to write in a letter dated 15 May 1984 that I had

“done an excellent job of setting out the problems afflicting our economic policies, unfortunately government-made problems!”

Also Jagdish may or may not have remembered our only meeting, when he and I had had a long conversation on the sofas in the foyer of the IMF in Washington when I was a consultant there in 1993 and he had come to meet someone; he was surprisingly knowledgeable about my personal 1990 matter in the Supreme Court of India which astonished me until he told me his brother the Supreme Court judge had mentioned the case to him!

Now my 1984 work was amply scientific and scholarly in fully crediting a large number of works in the necessary bibliography, including Bhagwati’s important work with his co-authors. Specifically, Footnote 1 listed the literature saying:

“The early studies notably include: B. R. Shenoy, `A note of dissent’, Papers relating to the formulation of the Second Five-Year Plan, Government of India Planning Commission, Delhi, 1955; Indian Planning and Economic Development, Asia Publishing, Bombay, 1963, especially pp. 17-53; P. T. Bauer, Indian Economic Policy and Development, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1961; M. Friedman, unpublished memorandum to the Government of India, November 1955 (referred to in Bauer, op. cit., p. 59 ff.); and, some years later, Sudha Shenoy, India : Progress or Poverty?, Research Monograph 27, Institute of Economic Affairs, London, 1971. Some of the most relevant contemporary studies are: B. Balassa, `Reforming the system of incentives in World Development, 3 (1975), pp. 365-82; `Export incentives and export performance in developing countries: a comparative analysis’, Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 114 (1978), pp. 24-61; The process of industrial development and alternative development strategies, Essays in International Finance No. 141, Princeton University, 1980; J. N. Bhagwati & P. Desai, India: Planning for Industrialisation, OECD, Paris : Oxford University Press, 1970; `Socialism and Indian Economic Policy’, World Development, 3 (1975), pp. 213-21; J. N. Bhagwati & T. N. Srinivasan, Foreign-trade Regimes and Economic Development: India, National Bureau of Economic Research, New York, 1975; Anne O. Krueger, `Indian planning experience’, in T. Morgan et al. (eds.), Readings in Economic Development, Wadsworth, California, 1963, pp. 403-20; `The political economy of the rent-seeking society, American Economic Review, 64 (June 1974); The Benefits and Costs of Import-Substitution in India: a Microeconomic Study, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1975; Growth, distortions and patterns of trade among many countries, Studies in International Finance, Princeton University, 1977; Uma Lele, Food grain marketing in India : private performance and public policy, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1971; T. W. Schultz (ed.), Distortions in agricultural incentives, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1978; V. Sukhatme, “The utilization of high-yielding rice and wheat varieties in India: an economic assessment”, University of Chicago PhD thesis, 1977….”

There were two specific references to Bhagwati’s work with Srinivasan:

“Jagdish Bhagwati and T. N. Srinivasan put it as follows : `The allocation of foreign exchange among alternative claimants and users in a direct control system . . .would presumably be with reference to a well-defined set of principles and criteria based on a system of priorities. In point of fact, however, there seem to have been few such criteria, if any, followed in practice.’”

and

“But as Bhagwati and Srinivasan report, `. . . the sheer weight of numbers made any meaningful listing of priorities extremely difficult. The problem was Orwellian: all industries had priority and how was each sponsoring authority to argue that some industries had more priority than others? It is not surprising, therefore, that the agencies involved in determining allocations by industry fell back on vague notions of “fairness”, implying pro rata allocations with reference to capacity installed or employment, or shares defined by past import allocations or similar rules of thumb’”

and one to Bhagwati and Desai:

“The best descriptions of Indian industrial policy are still to be found in Bhagwati and Desai (1970)…”

Professors Bhagwati and Panagriya have not apparently referred to anything beyond these joint works of Bhagwati’s dated 1970 with Padma Desai and 1975 with TN Srinivasan. They have not claimed Bhagwati did anything by way of either publication or political activity in relation to India’s economic policy between May 1984, when he read my soon-to-be-published-work and found I had

“done an excellent job of setting out the problems afflicting our economic policies, unfortunately government-made problems”,

and September 1990 when I gave Rajiv the University of Hawaii perestroika-for-India project results developed since 1986, which came to politically spark the 1991 reform in the Congress’s highest echelons from months before Rajiv’s assassination.

There may have been no such claim made by Bhagwati and Panagariya because there may be no such evidence. Between 1984 and 1990, Professor Bhagwati’s research interests were away from Indian economic policy while his work on India through 1970 and 1975 had been fully and reasonably accounted for as of 1984 by myself.

What is left remaining is Bhagwati’s statement :

“When finance minister Manmohan Singh was in New York in 1992, he had a lunch for many big CEOs whom he was trying to seduce to come to India. He also invited me and my wife, Padma Desai, to the lunch. As we came in, the FM introduced us to the invitees and said: ‘These friends of mine wrote almost a quarter century ago [India: Planning for Industrialisation was published in 1970 by Oxford] recommending all the reforms we are now undertaking. If we had accepted the advice then, we would not be having this lunch as you would already be in India’

Now this light self-deprecating reference by Manmohan at an investors’ lunch in New York “for many big CEOs” was an evident attempt at political humour written by his speech-writer. It was clearly, on its face, not serious history. If we test it as serious history, it falls flat so we may only hope Manmohan Singh, unlike Jagdish Bhagwati, has not himself come to believe his own reported joke as anything more than that.

The Bhagwati-Desai volume being referred to was developed from 1966-1970. India saw critical economic and political events in 1969, in 1970, in 1971, in 1972, in 1975, in 1977, etc.

Those were precisely years during which Manmohan Singh himself moved from being an academic to becoming a Government of India official, working first for MG Kaul, ICS, and then in 1971 coming to the attention of PN Haksar, Indira Gandhi’s most powerful bureaucrat between 1967 and 1974: Haksar himself was Manmohan Singh’s acknowledged mentor in the Government, as Manmohan told Mark Tully in an interview.

After Manmohan visited our Paris home in 1973 to talk to me about economics, my father — who had been himself sent to the Paris Embassy by Haksar in preparation for Indira Gandhi’s visit in November 1971 before the Bangladesh war —

had told me Manmohan was very highly regarded in government circles with economics degrees from both Cambridge and Oxford, and my father had added, to my surprise, what was probably a Haksarian governmental view that Manmohan was expected to be India’s Prime Minister some day. That was 1973.

PN Haksar had been the archetypal Nehruvian Delhi intellectual of a certain era, being both a fierce nationalist and a fierce pro-USSR leftist from long before Independence. I met him once on 23 March 1991, on the lawns of 10 Jan Path at the launch of General V Krishna Rao’s book on Indian defence which Rajiv was releasing, and Haksar gave a speech to introduce Rajiv (as if Rajiv needed introduction on the lawns of his own residence); Haksar was in poor health but he seemed completely delighted to be back in favour with Rajiv, after years of having been treated badly by Indira and her younger son.

Had Manmohan Singh in the early 1970s gone to Haksar — the architect of the nationalisation of India’s banking going on right then — and said “Sir, this OECD study by my friend Bhagwati and his wife says we should be liberalising foreign trade and domestic industry”, Haksar would have been astonished and sent him packing.

There was a war on, plus a massive problem of 10 million refugees, a new country to support called Bangladesh, a railway strike, a bad crop, repressed inflation, shortages, and heaven knows what more, besides Nixon having backed Yahya Khan, Tikka Khan et al.

Then after Bangladesh and the railway strike etc, came the rise of the politically odious younger son of Indira Gandhi and his friends (at least one of whom is today Sonia Gandhi’s gatekeeper) followed by the internal political Emergency, the grave foreign-fueled problem of Sikh separatism and its control, the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her own Sikh bodyguards, and the Rajiv Gandhi years as Prime Minister.

Certainly it was Rajiv’s arrival in office and Benazir’s initial return to Pakistan, along with the rise of Michael Gorbachev in the changing USSR, that inspired me in far away Hawaii in 1986 to design with Ted James the perestroika-projects for India and Pakistan which led to our two volumes, and which, thanks to Siddhartha Shankar Ray, came to reach Rajiv Gandhi in Opposition in September 1990 as he sat somewhat forlornly at 10 Jan Path after losing office. “There is a tide in the affairs of men, Which taken at the flood, leads on to fortune….

My friend and collaborator Ted James died of cancer in Manila in May 2010; earlier that year he came to say publicly