Preface

27 April 2015 from Twitter: “My Pakistani hosts never managed to go thru w their 2010/11 invitation I speak in Lahore on Kashmir. After #SabeenMahmud s murder, I decline”

October 2015 from Twitter: I have started a quite thorough critique under #kasuri etc at Twitter of the extremely peculiar free publicity given in Delhi and Mumbai power circles to the dressed up (and false) ISI/Hurriyat narrative of KM Kasuri; the Musharraf “demilitarisation/borderless” idea that Mr Kasuri promotes is originally mine from our Pakistan book in America in the 1980s, which I brought to the attention of both sides (and the USA) in Washington in 1993 but which I myself later rejected as naive and ignorant after the Pakistani aggression in Kargil in 1999, especially the murder of Lt Kalia and his platoon as POWs. https://independentindian.com/2006/12/15/what-to-tell-musharraf-peace-is-impossible-without-non-aggressive-pakistani-intentions/ https://independentindian.com/2008/11/15/of-a-new-new-delhi-myth-and-the-success-of-the-university-of-hawaii-1986-1992-pakistan-project/

see too https://independentindian.com/2011/10/13/my-seventy-one-notes-at-facebook-etc-on-kashmir-pakistan-and-of-course-india-listed-thanks-to-jd/

I have also now made clear how and why my Lahore lecture (confirmed by the Pakistani envoy to Delhi personally phoning me of his own accord at home on 3 March 2011, followed the next day by the Indian Foreign Secretary phoning to give me an appointment to brief her about my talk upon my return) came to be sabotaged by two Pakistanis and two Indian politicians associated with them. (Both of the Indian politicians had bad karma catch up immediately afterwards!)

Original Preface 22 November 2011: Exactly a year ago, in late October-November 2010, I received a very kind invitation from the Lahore Oxford and Cambridge Society to speak there on this subject. Mid March 2011 was a tentative date for this lecture from which the text below is dated. The lecture has yet to take place for various reasons but as there is demand for its content, I am releasing the part which was due to be released in any case to my Pakistani hosts ahead of time — after all, it would have been presumptuous of me to seek to speak in Lahore on Pakistan’s viewpoint on Kashmir, hence I instead planned to release my understanding of that point of view ahead of time and open it to the criticism of my hosts. The structure of the remainder of the talk may be surmised too from the Contents. The text and argument are mine entirely, the subject of more than 25 years of research and reflection, and are under consideration of publication as a book by Continuum of London and New York. If you would like to comment, please feel free to do so, if you would like to refer to it in an online publication, please give this link, if you would like to refer to it in a paper-publication, please email me. Like other material at my site, it is open to the Fair Use rule of normal scholarship.

On the Alternative Theories of Pakistan and India about Jammu & Kashmir (And the One and Only Way These May Be Peacefully Reconciled): An Exercise in Economics, Politics, Moral Philosophy & Jurisprudence

by

Subroto (Suby) Roy

Lecture to the Oxford and Cambridge Society of Lahore

March 14, 2011 (tentative)

“What is the use of studying philosophy if all that does for you is to enable you to talk with some plausibility about some abstruse questions of logic, etc., & if it does not improve your thinking about the important questions of everyday life?” Wittgenstein, letter to Malcolm, 1944

“India is the greatest Muslim country in the world.”

Sir Muhammad Iqbal, 1930, Presidential Address to the Muslim League, Allahabad

“Where be these enemies?… See, what a scourge is laid upon your hate,… all are punish’d.” Shakespeare

Dr Roy’s published works include Philosophy of Economics: On the Scope of Reason in Economic Inquiry (London & New York: Routledge, 1989, 1991); Pricing, Planning & Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1984); and, edited with WE James, Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s (Hawaii MS 1989, Sage 1992) & Foundations of Pakistan’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s (Hawaii MS 1989, Sage 1992, OUP Karachi 1993); and, edited with John Clarke, Margaret Thatcher’s Revolution: How it Happened and What it Meant (London & New York: Continuum 2005). He graduated in 1976 with a first from the London School of Economics in mathematical economics, and received the PhD in economics at Cambridge in 1982 under Professor Frank Hahn for the thesis “On liberty & economic growth: preface to a philosophy for India”. In the United States for 16 years he was privileged to count as friends Professors James Buchanan, Milton Friedman, TW Schultz, Max Black and Sidney Alexander. From September 18 1990 he was an adviser to Rajiv Gandhi and contributed to the origins of India’s 1991 economic reform. He blogs at http://www.independentindian.com.

CONTENTS

Part I

-

Introduction

-

Pakistan’s Point of View (or Points of View)

(a) 1930 Sir Muhammad Iqbal

(b) 1933-1948 Chaudhury Rahmat Ali

(c) 1937-1941 Sir Sikander Hayat Khan

(d) 1937-1947 Quad-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah

(e) 1940s et seq Maulana Abul Ala Maudoodi

(f) 1947-1950 Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, 1966 President Ayub Khan, 2005 Govt of Pakistan, 2007 President Musharraf, 2008 FM Qureshi, 2011 Kashmir Day

Part II

-

India’s Point of View: British Negligence/Indifference during the Transfer of Power, A Case of Misgovernance in the Chaotic Aftermath of World War II

(a) Rhetoric: Whose Pakistan? Which Kashmir?

(b) Law: (i) Liaquat-Zafrullah-Abdullah-Nehru United in Error Over the Second Treaty of Amritsar! Dogra J&K subsists Mar 16 1846-Oct 22 1947. Aggression, Anarchy, Annexations: The LOC as De Facto Boundary by Military Decision Since Jan 1 1949. (ii) Legal Error & Confusion Generated by 12 May 1946 Memorandum. (iii) War: Dogra J&K attacked by Pakistan, defended by India: Invasion, Mutiny, Secession of “Azad Kashmir” & Gilgit, Rape of Baramulla, Siege of Skardu.

-

Politics: What is to be Done? Towards Truths, Normalisation, Peace in the 21st Century

The Present Situation is Abnormal & Intolerable. There May Be One (and Only One) Peacable Solution that is Feasible: Revealing Individual Choices Privately with Full Information & Security: Indian “Green Cards”/PIO-OCI status for Hurriyat et al: A Choice of Nationality (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran). Of Flags and Consulates in Srinagar & Gilgit etc: De Jure Recognition of the Boundary, Diplomatic Normalisation, Economic & Military Cooperation.

-

Appendices:

(a) History of Jammu & Kashmir until the Dogra Native State

(b) Pakistan’s Allies (including A Brief History of Gilgit)

(c) India’s Muslim Voices

(d) Pakistan’s Muslim Voices: An Excerpt from the Munir Report

Part I

1. Introduction

For a solution to Jammu & Kashmir to be universally acceptable it must be seen by all as being lawful and just. Political opinion across the subcontinent — in Pakistan, in India, among all people and parties in J&K, those loyal to India, those loyal to Pakistan, and any others — will have to agree that, all things considered, such is the right course of action for everyone today in the 21st Century, which means too that the solution must be consistent with the principal known facts of history as well as account reasonably for all moral considerations.

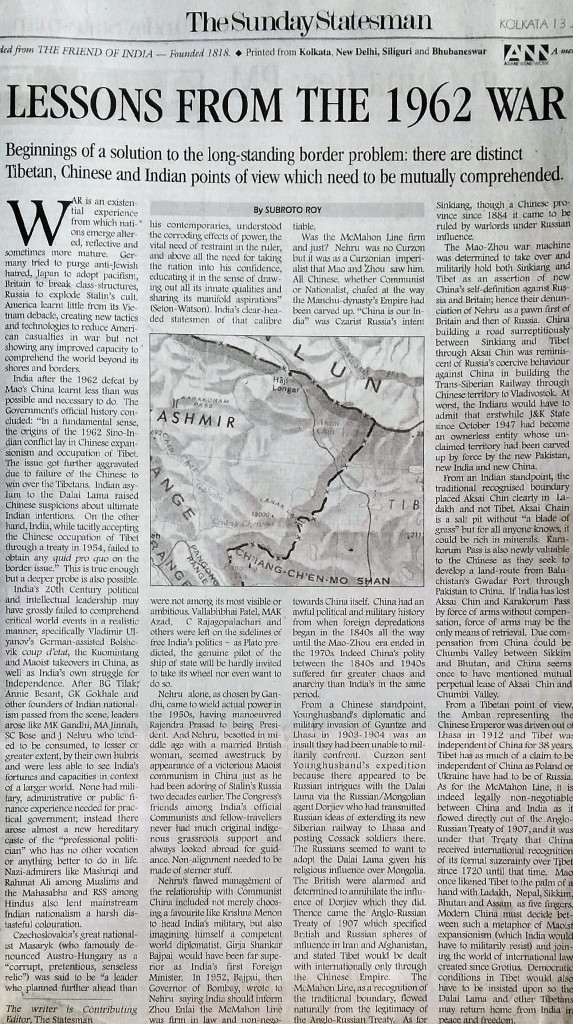

I claim to have found such a solution, indeed I shall even say it is the only such solution (in terms of theoretical economics, it is the unique solution) and plan with your permission to describe its main outlines at this distinguished gathering. I have not invented it overnight but it is something developed over a quarter century, milestones along the way being the books emerging from the University of Hawaii “perestroika” projects for India and Pakistan that I and the late WE James led 25 years ago, and a lecture I gave at Washington’s Heritage Foundation in June 1998, as well as sets of newspaper articles published between 2005 and 2008, one in Dawn of Karachi and others in The Statesman of New Delhi and Kolkata.

Before I start, allow me for a moment to remind just how complex and intractable the problem we face has been, and, therefore, quite how large my ambition is in claiming today to be able to resolve it.

“Kashmir is in the Supreme National Interest of Pakistan”, says Pakistan.

“Kashmir is an Integral Part of India”, says India.

“Kashmir is an Integral Part of Pakistan”, says Pakistan.

“Kashmir is in the Supreme National Interest of India”, says India.

And so it goes, in what over the decades has been all too often a Dialogue of the Deaf. How may such squarely opposed positions be reconciled without draining public resources even further through wasteful weaponry and confrontation of standing armies, or, what is worse, using these weapons and armies in war, plunging the subcontinent into an abyss of chaos and destruction for generations to come? How is it possible?

I shall suggest a road can be found only when we realize Pakistan, India and J&K each have been and are going to remain integral to one another — in their histories, their geographies, their economies and their societies. The only place they may need to differ, where we shall want them to differ, is their politics and political systems. We should not underestimate how much mutual hatred and mutual fear has arisen naturally on all sides over the decades as a result of bloodshed and suffering all around, and the fact must also be accounted for that people simply may not be in a calm-enough emotional state to want to be part of processes seeking resolution; at the same time, it bears to be remembered that although Pakistan and India have been at war more than once and war is always a very serious and awful thing, they have never actually declared war against the other nor have they ever broken diplomatic relations – in fact in some ways it has always seemed like some very long and protracted fraternal Civil War between us where we think we know one another so well and yet come to be surprised more by one another’s virtues than by one another’s vices.

Secondly, with any seemingly intractable problem, dialogue can stall or be aborted due to normal human failings of impatience or lack of good will or lack of good humour or lack of a scientific attitude towards finding facts, or plain mutual miscomprehension of one another’s points of view through ignorance or laziness or negligence. In case of Pakistan and India over J&K, there has been the further critical complication that we of this generation did not cause this problem — it has been something inherited by us from not even our fathers but our grandfathers! It is two generations old. Each side must respect the words and deeds of its forebears but also may have to frankly examine in a scientific spirit where errors of fact or judgment may have occurred back then. The antagonistic positions have changed only slightly over two generations, and one reason dialogue stalls or gets aborted today is because positions have become frozen for more than half a century and merely get repeated endlessly. On top of such frozen positions have been piled pile upon pile of further vast mortal complications: the 1965 War, the 1971 secession of East Pakistan, the 1999 Kargil War, the 2008 Mumbai massacres. Only cacophony results if we talk about everything at once, leaving the status quo of a dangerous expensive confrontation to continue.

I propose instead to focus as specifically and precisely as possible on how Jammu & Kashmir became a problem at all during those crucial decades alongside the processes of Indian Independence, World War II, the Pakistan Movement and creation of Pakistan, accompanied by the traumas and bloodshed of Partition.

Having addressed that — and it is only fair to forewarn this eminent Lahore audience that such a survey of words, deeds and events between the 1930s and 1950s tends to emerge in India’s favour — I propose to “fast-forward” to current times, where certain new facts on the ground appear much more adverse to India, and finally seek to ask what can and ought to be done, all things considered, today in the circumstances of the 21st Century. There are four central facts, let me for now call them Fact A, Fact B, Fact C and Fact D, which have to be accepted by both countries in good faith and a scientific spirit. Facts A and B are historical in nature; Pakistan has refused to accept them. Facts C and D are contemporary in nature; official political India and much of the Indian media too often have appeared wilfully blind to them. The moment all four facts come to be accepted by all, the way forward becomes clear. We have inherited this grave mortal problem which has so badly affected the ordinary people of J&K in the most terrible and unacceptable manner, but if we fail to understand and resolve it, our children and grandchildren will surely fail even worse — we may even leave them to cope with the waste and destruction of further needless war or confrontation, indeed with the end of the subcontinent as we have received and known it in our time.

2. Pakistan’s Point of View (Or Points of View)

1930 Sir Muhammad Iqbal

This audience will need no explanation why I start with Sir Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), the poetic and spiritual genius who in the 20th Century inspired the notion of a Muslim polity in NorthWestern India, whose seminal 1930 presidential speech to the Muslim League in Allahabad lay the foundation stone of the new country that was yet to be. He did not live to see Pakistan’s creation yet what may be called the “Pakistan Principle” was captured in his words:

“I would like to see the Punjab, Northwest Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North West Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims at least of Northwest India… India is the greatest Muslim country in the world. The life of Islam as a cultural force in this living country very largely depends on its centralization in a specified territory”.

He did not see such a consolidated Muslim state being theocratic and certainly not one filled with bigotry or “Hate-Hindu” campaigns:

“A community which is inspired by feelings of ill-will towards other communities is low and ignoble. I entertain the highest respect for the customs, laws, religious and social institutions of other communities… Yet I love the communal group which is the source of my life and my behaviour… Nor should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states…. I therefore demand the formation of a consolidated Muslim state in the best interests of India and Islam. For India it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power, for Islam an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian Imperialism was forced to give it, to mobilise its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and the spirit of modern times.”[1]

Though Kashmiri himself, in fact a founding member of the “All-India Jammu & Kashmir Muslim Conference of Lahore and Simla”, and a hero and role model for the young Sheikh Abdullah (1905-1982), Allama Iqbal was explicitly silent about J&K being part of the new political entity he had come to imagine. I do not say he would not have wished it to be had he lived longer; what I am saying is that his original vision of the consolidated Muslim state which constitutes Pakistan today (after a Partitioned Punjab) did not include Jammu & Kashmir. Rather, it was focused on the politics of British India and did not mention the politics of Kashmir or any other of the so-called “Princely States” or “Native States” of “Indian India” who constituted some 1/3rd of the land mass and 1/4th of the population of the subcontinent. Twenty years ago I called this “The Paradox of Kashmir”, namely, that prior to 1947 J&K hardly seemed to appear in any discussion at all for a century, yet it has consumed almost all discussion and resources ever since.

Secondly, this audience will see better than I can the significance of Dr Iqbal’s saying the Muslim political state of his conception needed

“an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian Imperialism was forced to give it”

and instead seek to

“mobilise its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and the spirit of modern times”.

Dr Iqbal’s Pakistan Principle appears here the polar opposite of Pakistan’s 18th & 19th Century pre-history represented by Shah Waliullah (1703-1762)[2] saying

“We are an Arab people whose fathers have fallen in exile in the country of Hindustan, and Arabic genealogy and Arabic language are our pride”

or Sayyid Ahmed Barelwi (1786-1831) saying

“We must repudiate all those Indian, Persian and Roman customs which are contrary to the Prophet’s teaching”.[3]

Some 25 years after the Allahabad address, the Munir Report in 1954 echoed Dr Iqbal’s thought when it observed about medieval military conquests

“It is this brilliant achievement of the Arabian nomads …that makes the Musalman of today live in the past and yearn for the return of the glory that was Islam… Little does he understand that the forces which are pitted against him are entirely different from those against which early Islam had to fight… Nothing but a bold reorientation of Islam to separate the vital from the lifeless can preserve it as a World Idea and convert the Musalman into a citizen of the present and the future world from the archaic incongruity that he is today…” [4]

1933-1947 Chaudhury Rahmat Ali

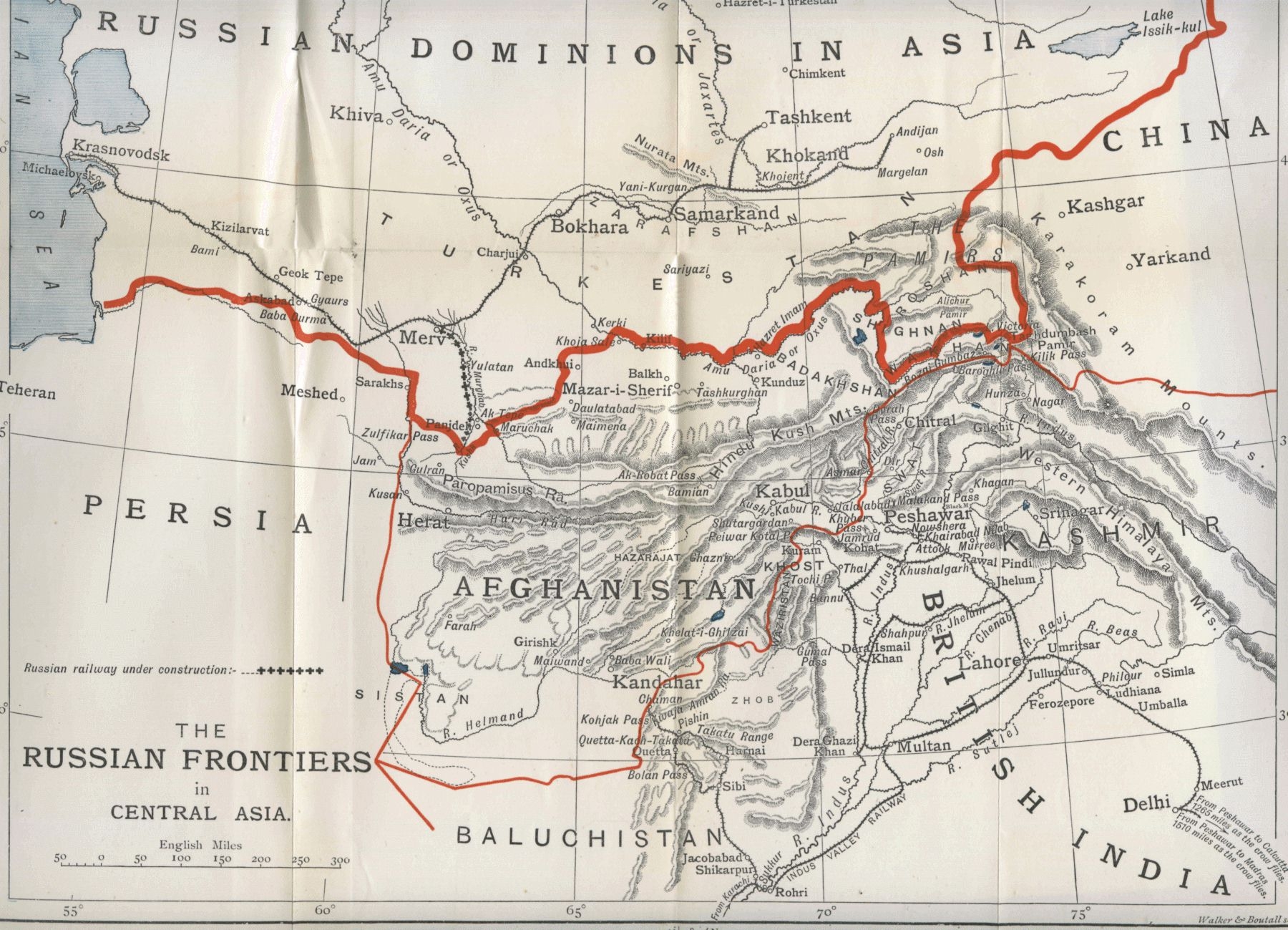

Dr Iqbal’s young follower, the radical Cambridge pamphleteer Chaudhury Rahmat Ali (1895-1951) drew a picture not of Muslim tolerance and coexistence with Hindus in a peaceful India but of aggression towards Hindus and domination by Muslims over the subcontinent and Asia itself. Rahmat Ali had been inspired by Dr Iqbal’s call for a Muslim state in Northwest India but found it vague and was disappointed Iqbal had not pressed it at the Third Round Table Conference. In 1933, reportedly on the upper floor of a London omnibus, he invented for the then-imagined political entity the name “PAKSTAN”, P for his native Punjab, A for Afghania, K for Kashmir, S for Sind, and STAN for Balochistan. He sought a meeting with Mr Jinnah in London — “Jinnah disliked Rahmat Ali’s ideas and avoided meeting him”[5] but did meet him. There is a thesis yet to be written on how Europe’s inter-War ideologies affected political thinking on the subcontinent. Rahmat Ali’s vituperative views about Hindus were akin to others about Jews (and Muslims too) at the time, all models or counterfoils for one another in the fringes of Nazism. He referred to the Indian nationalist movement as a “British-Banya alliance”, declined to admit India had ever existed and personally renamed the subcontinent “Dinia” and the seas around it the “Pakian Sea”, the “Osmanian Sea” etc. He urged Sikhs to rise up in a “Sikhistan” and urged all non-Hindus to rise up in war against Hindus. Given the obscurity of his life before his arrival at Cambridge’s Emmanuel College, what experiences may have led him to such views are not known.

All this was anathema to Mr Jinnah, the secular constitutionalist embarrassed by a reactionary Muslim imperialism in that rapidly modernising era that was the middle of the 20th Century. When Rahmat Ali pressed the ‘Pakstan’ acronym, Mr Jinnah said Bengal was not in it and Muslim minority regions were absent. At this Chaudhury-Sahib produced a general scheme of Muslim domination all over the subcontinent: there would be “Pakstan” in the northwest including Kashmir, Delhi and Agra; “Bangistan” in Bengal; “Osmanistan” in Hyderabad; “Siddiquistan” in Bundelhand and Malwa; “Faruqistan” in Bihar and Orissa; “Haideristan” in UP; “Muinistan” in Rajasthan; “Maplistan” in Kerala; even “Safiistan” in “Western Ceylon” and “Nasaristan” in “Eastern Ceylon”, etc. In 1934 he published and widely circulated such a diagram among Muslims in Britain at the time. He was not invited to the Lahore Resolution which did not refer to Pakistan though came to be called the Pakistan Resolution. When he landed in the new Pakistan, he was apparently arrested and deported back and was never granted a Pakistan passport. From England, he turned his wrath upon the new government, condemning Mr Jinnah as treacherous and newly re-interpreting his acronym to refer to Punjab, Afghania, Kashmir, Iran, Sindh, Tukharistan (sic), Afghanistan, and Balochistan. The word “pak” coincidentally meant pure, so he began to speak of Muslims as “the Pak” i.e. “the pure” people, and of how the national destiny of the new Pakistan was to liberate “Pak” people everywhere, including the new India, and create a “Pak Commonwealth of Nations” stretching from Arabia to the Indies. The map he now drew placed the word “Punjab” over J&K, and saw an Asia dominated by this “Pak” empire. Shunned by officialdom of the new Pakistan, Chaudhury-Sahib was a tragic figure who died in poverty and obscurity during an influenza epidemic in 1951; the Master of Emmanuel College paid for his funeral and was apparently later reimbursed for this by the Government of Pakistan. In recent years he has undergone a restoration, and his grave at Cambridge has become a site of pilgrimage for ideologues, while his diagrams and writings have been reprinted in Pakistan’s newspapers as recently as February 2005.

1937-1941 Sir Sikander Hayat Khan

Chaudhary Rahmat Ali’s harshest critic at the time was the eminent statesman and Premier of Punjab Sir Sikander Hayat Khan (1892-1942), partner of the 1937 Sikander-Jinnah Pact, and an author of the Lahore Resolution. His statement of 11 March 1941 in the Punjab Legislative Assembly Debates is a classic:

“No Pakistan scheme was passed at Lahore… As for Pakistan schemes, Maulana Jamal-ud-Din’s is the earliest…Then there is the scheme which is attributed to the late Allama Iqbal of revered memory. He, however, never formulated any definite scheme but his writings and poems have given some people ground to think that Allama Iqbal desired the establishment of some sort of Pakistan. But it is not difficult to explode this theory and to prove conclusively that his conception of Islamic solidarity and universal brotherhood is not in conflict with Indian patriotism and is in fact quite different from the ideology now sought to be attributed to him by some enthusiasts… Then there is Chaudhuri Rahmat Ali’s scheme (*laughter*)…it was widely circulated in this country and… it was also given wide publicity at the time in a section of the British press. But there is another scheme…it was published in one of the British journals, I think Round Table, and was conceived by an Englishman…..the word Pakistan was not used at the League meeting and this term was not applied to (the League’s Lahore) resolution by anybody until the Hindu press had a brain-wave and dubbed it Pakistan…. The ignorant masses have now adopted the slogan provided by the short-sighted bigotry of the Hindu and Sikh press…they overlooked the fact that the word Pakistan might have an appeal – a strong appeal – for the Muslim masses. It is a catching phrase and it has caught popular imagination and has thus made confusion worse confounded…. So far as we in the Punjab are concerned, let me assure you that we will not countenance or accept any proposal that does not secure freedom for all (*cheers*). We do not desire that Muslims should domineer here, just as we do not want the Hindus to domineer where Muslims are in a minority. Now would we allow anybody or section to thwart us because Muslims happen to be in a majority in this province. We do not ask for freedom that there may be a Muslim Raj here and Hindu Raj elsewhere. If that is what Pakistan means I will have nothing to do with it. If Pakistan means unalloyed Muslim Raj in the Punjab then I will have nothing to do with it (*hear, hear*)…. If you want real freedom for the Punjab, that is to say a Punjab in which every community will have its due share in the economic and administrative fields as partners in a common concern, then that Punjab will not be Pakistan but just Punjab, land of the five rivers; Punjab is Punjab and will always remain Punjab whatever anybody may say (*cheers*). This, then, briefly is the future which I visualize for my province and for my country under any new constitution.

Intervention (Malik Barkat Ali): The Lahore resolution says the same thing.

Premier: Exactly; then why misinterpret it and try to mislead the masses?…”

1937-1947 Quad-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah

During the Third Round Table Conference, Dr Iqbal persuaded Mr Jinnah (1876-1948) to return to India; Mr Jinnah, from being settled again in his London law practice, did so in 1934. But following the 1935 Govt of India Act, the Muslim League failed badly when British India held its first elections in 1937 not only in Bengal and UP but in Punjab (one seat), NWFP and Sind.

World War II, like World War I a couple of brief decades earlier, then changed the political landscape completely. Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 and Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September. The next day, India’s British Viceroy (Linlithgow) granted Mr Jinnah the political parity with Congress that he had sought.[6] Professor Francis Robinson suggests that until 4 September 1939 the British

“had had little time for Jinnah and his League. The Government’s declaration of war on Germany on 3 September, however, transformed the situation. A large part of the army was Muslim, much of the war effort was likely to rest on the two Muslim majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal. The following day, the Viceroy invited Jinnah for talks on an equal footing with Gandhi…. As the Congress began to demand immediate independence, the Viceroy took to reassuring Jinnah that Muslim interests would be safeguarded in any constitutional change. Within a few months, he was urging the League to declare a constructive policy for the future, which was of course presented in the Lahore Resolution[7]…. In their August 1940 offer, the British confirmed for the benefit of Muslims that power would not be transferred against the will of any significant element in Indian life. And much the same confirmation was given in the Cripps offer nearly two years later…. Throughout the years 1940 to 1945, the British made no attempt to tease out the contradictions between the League’s two-nation theory, which asserted that Hindus and Muslims came from two different civilisations and therefore were two different nations, and the Lahore Resolution, which demanded that ‘Independent States’ should be constituted from the Muslim majority provinces of the NE and NW, thereby suggesting that Indian Muslims formed not just one nation but two. When in 1944 the governors of Punjab and Bengal urged such a move on the Viceroy, Wavell ignored them, pressing ahead instead with his own plan for an all-India conference at Simla. The result was to confirm, as never before in the eyes of leading Muslims in the majority provinces, the standing of Jinnah and the League. Thus, because the British found it convenient to take the League seriously, everyone had to as well—Congressmen, Unionists, Bengalis, and so on…”[8]

Mr Jinnah was himself amazed by the new British attitude towards him:

“(S)uddenly there was a change in the attitude towards me. I was treated on the same basis as Mr Gandhi. I was wonderstruck why all of a sudden I was promoted and given a place side by side with Mr Gandhi.”

Britain, threatened for its survival, faced an obdurate Indian leadership and even British socialists sympathetic to Indian aspirations grew cold (Gandhi dismissing the 1942 Cripps offer as a “post-dated cheque on a failing bank”). Official Britain’s loyalties had been consistently with those who had been loyal to them, and it was unsurprising there would be a tilt to empower Mr Jinnah soon making credible the real possibility of Pakistan.[9] By 1946, Britain was exhausted, pre-occupied with rationing, Berlin, refugee resettlement and countless other post-War problems — Britain had not been beaten in war but British imperialism was finished because of the War. Muslim opinion in British India had changed decisively in the League’s favour. But the subcontinent’s political processes were drastically spinning out of everyone’s control towards anarchy and blood-letting. Implementing a lofty vision of a cultured progressive consolidated Muslim state in India’s NorthWest descended into “Direct Action” with urban mobs shouting Larke lenge Pakistan; Marke lenge Pakistan; Khun se lenge Pakistan; Dena hoga Pakistan.[10]

We shall return to Mr Jinnah’s view on the legal position of the “Native Princes” of “Indian India” during this critical time, specifically J&K; here it is essential before proceeding only to record his own vision for the new Pakistan as recorded by the profoundly judicious report of Justice Munir and Justice Kayani a mere half dozen years later:

“Before the Partition, the first public picture of Pakistan that the Quaid-i-Azam gave to the world was in the course of an interview in New Delhi with Mr. Doon Campbell, Reuter’s Correspondent. The Quaid-i-Azam said that the new State would be a modern democratic State, with sovereignty resting in the people and the members of the new nation having equal rights of citizenship regardless of their religion, caste or creed. When Pakistan formally appeared on the map, the Quaid-i-Azam in his memorable speech of 11th August 1947 to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, while stating the principle on which the new State was to be founded, said:—‘All the same, in this division it was impossible to avoid the question of minorities being in one Dominion or the other. Now that was unavoidable. There is no other solution. Now what shall we do? Now, if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people, and specially of the masses and the poor. If you will work in co-operation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in a spirit that every one of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste or creed, is first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges and obligations., there will be no end to the progress you will make. “I cannot emphasise it too much. We should begin to work in that spirit and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities—the Hindu community and the Muslim community— because even as regards Muslims you have Pathana, Punjabis, Shias, Sunnis and so on and among the Hindus you have Brahmins, Vashnavas, Khatris, also Bengalis, Madrasis and so on—will vanish. Indeed if you ask me this has been the biggest hindrance in the way of India to attain its freedom and independence and but for this we would have been free peoples long long ago. No power can hold another nation, and specially a nation of 400 million souls in subjection; nobody could have conquered you, and even if it had happened, nobody could have continued its hold on you for any length of time but for this (Applause). Therefore, we must learn a lesson from this. You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed— that has nothing to do with the business of the State (Hear, hear). As you know, history shows that in England conditions sometime ago were much worse than those prevailing in India today. The Roman Catholics and the Protestants persecuted each other. Even now there are some States in existence where there are discriminations made and bars imposed against a particular class. Thank God we are not starting in those days. We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State (Loud applause). The people of England in course of time had to face the realities of the situation and had to discharge the responsibilities and burdens placed upon them by the Government of their country and they went through that fire step by step. Today you might say with justice that Roman Catholics and Protestants do not exist: what exists now is that every man is a citizen, an equal citizen, of Great Britain and they are all members of the nation. “Now, I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State’. The Quaid-i-Azam was the founder of Pakistan and the occasion on which he thus spoke was the first landmark in the history of Pakistan. The speech was intended both for his own people including non-Muslims and the world, and its object was to define as clearly as possible the ideal to the attainment of which the new State was to devote all its energies. There are repeated references in this speech to the bitterness of the past and an appeal to forget and change the past and to bury the hatchet. The future subject of the State is to be a citizen with equal rights, privileges and obligations, irrespective of colour, caste, creed or community. The word ‘nation’ is used more than once and religion is stated to have nothing to do with the business of the State and to be merely a matter of personal faith for the individual.”

1940s et seq Maulana Abul Ala Maudoodi, Amir Jama’at-i-Islami

The eminent theologian Maulana Abul Ala Maudoodi (1903-1979), founder of the Jama’at-i-Islami, had been opposed to the Pakistan Principle but once Pakistan was created he became the most eminent votary of an Islamic State, declaring:

“That the sovereignty in Pakistan belongs to God Almighty alone and that the Government of Pakistan shall administer the country as His agent”.

In such a view, Islam becomes

“the very antithesis of secular Western democracy. The philosophical foundation of Western democracy is the sovereignty of the people. Lawmaking is their prerogative and legislation must correspond to the mood and temper of their opinion… Islam… altogether repudiates the philosophy of popular sovereignty and rears its polity on the foundations of the sovereignty of God and the viceregency (Khilafat) of man.”

Maulana Maudoodi was asked by Justice Munir and Justice Kayani:

“Q.—Is a country on the border of dar-ul-Islam always qua an Islamic State in the position of dar-ul-harb ?

A.—No. In the absence of an agreement to the contrary, the Islamic State will be potentially at war with the non-Muslim neighbouring country. The non-Muslim country acquires the status of dar-ul-harb only after the Islamic State declares a formal war against it”.

“Q.—Is there a law of war in Islam?

A.—Yes.

Q.—Does it differ fundamentally from the modern International Law of war?

A.—These two systems are based on a fundamental difference.

Q.—What rights have non-Muslims who are taken prisoners of war in a jihad?

A.—The Islamic law on the point is that if the country of which these prisoners are nationals pays ransom, they will be released. An exchange of prisoners is also permitted. If neither of these alternatives is possible, the prisoners will be converted into slaves for ever. If any such person makes an offer to pay his ransom out of his own earnings, he will be permitted to collect the money necessary for the fidya (ransom).

Q.—Are you of the view that unless a Government assumes the form of an Islamic Government, any war declared by it is not a jihad?

A.—No. A war may be declared to be a jihad if it is declared by a national Government of Muslims in the legitimate interests of the State. I never expressed the opinion attributed to me in Ex. D. E. 12:— (translation)‘The question remains whether, even if the Government of Pakistan, in its present form and structure, terminates her treaties with the Indian Union and declares war against her, this war would fall under the definition of jihad? The opinion expressed by him in this behalf is quite correct. Until such time as the Government becomes Islamic by adopting the Islamic form of Government, to call any of its wars a jihad would be tantamount to describing the enlistment and fighting of a non-Muslim on the side of the Azad Kashmir forces jihad and his death martyrdom. What the Maulana means is that, in the presence of treaties, it is against Shari’at, if the Government or its people participate in such a war. If the Government terminates the treaties and declares war, even then the war started by Government would not be termed jihad unless the Government becomes Islamic’.

….

“Q.—If we have this form of Islamic Government in Pakistan, will you permit Hindus to base their Constitution on the basis of their own religion?

A—Certainly. I should have no objection even if the Muslims of India are treated in that form of Government as shudras and malishes and Manu’s laws are applied to them, depriving them of all share in the Government and the rights of a citizen. In fact such a state of affairs already exists in India.”

.…

“Q.—What will be the duty of the Muslims in India in case of war between India and Pakistan?

A.—Their duty is obvious, and that is not to fight against Pakistan or to do anything injurious to the safety of Pakistan.”

1947-1950 PM Liaquat Ali Khan, 1966 Gen Ayub Khan, 2005 Govt of Pakistan et seq

In contrast to Maulana Maudoodi saying Islam was “the very antithesis of secular Western democracy”, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan (1895-1951)[11] during his first official visit in 1950 to North America was to say the new Pakistan, because it was Muslim, held Asia’s greatest democratic potential:

“At present there is no democracy in Asia which is more free and more unified than Pakistan; none so free from moral doubts and from strains between the various sections of the people.”

He told his audiences Pakistan was created because Hindus were people wedded to caste-differences where Pakistanis as Muslims had an egalitarian and democratic disposition:

“The Hindus, for example, believe in the caste system according to which some human beings are born superior to others and cannot have any social relations with those in the lower castes or with those who are not Hindus. They cannot marry them or eat with them or even touch them without being polluted. The Muslims abhor the caste system, as they are a democratic people and believe in the equality of men and equal opportunities for all, do not consider a priesthood necessary, and have economic laws and institutions which recognize the right of private ownership and yet are designed to promote the distribution of wealth and to put healthy checks on vast unearned accumulations… so the Hindus and the Muslims decided to part and divide British India into two independent sovereign states… Our demand for a country of our own had, as you see, a strong democratic urge behind it. The emergence of Pakistan itself was therefore the triumph of a democratic idea. It enabled at one stroke a democratic nation of eighty million people to find a place of its own in Asia, where now they can worship God in freedom and pursue their own way of life uninhibited by the domination or the influence of ways and beliefs that are alien or antagonistic to their genius.” [12]

President Ayub Khan would state in similar vein on 18 November 1966 at London’s Royal Institute of International Affairs:

“the root of the problem was the conflicting ideologies of India and Pakistan. Muslim Pakistan believed in common brotherhood and giving people equal opportunity. India and Hinduism are based on inequality and on colour and race. Their basic concept is the caste system… Hindus and Muslims could never live under one Government, although they might live side by side.”

Regarding J&K, Liaquat Ali Khan on November 4 1947 broadcast from here in Lahore that the 1846 Treaty of Amritsar was “infamous” in having caused an “immoral and illegal” ownership of Jammu & Kashmir. He, along with Mr Jinnah, had called Sheikh Abdullah a “goonda” and “hoodlum” and “Quisling” of India, and on February 4 1948 Pakistan formally challenged the sovereignty of the Dogra dynasty in the world system of nations. In 1950 during his North American visit though, the Prime Minister allowed that J&K was a “princely state” but said

“culturally, economically, geographically and strategically, Kashmir – 80 per cent of whose peoples like the majority of the people in Pakistan are Muslims – is in fact an integral part of Pakistan”;

“(the) bulk of the population (are) under Indian military occupation”.

Pakistan’s official self-image, portrayal of India, and position on J&K may have not changed greatly since her founding Prime Minister’s statements. For example, in June 2005 the website of the Government of Pakistan’s Permanent Mission at the UN stated:

“Q: How did Hindu Raja (sic) become the ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir?

A: Historically speaking Kashmir had been ruled by the Muslims from the 14th Century onwards. The Muslim rule continued till early 19th Century when the ruler of Punjab conquered Kashmir and gave Jammu to a Dogra Gulab Singh who purchased Kashmir from the British in 1846 for a sum of 7.5 million rupees.”

“India’s forcible occupation of the State of Jammu and Kashmir in 1947 is the main cause of the dispute. India claims to have ‘signed’ a controversial document, the Instrument of Accession, on 26 October 1947 with the Maharaja of Kashmir, in which the Maharaja obtained India’s military help against popular insurgency. The people of Kashmir and Pakistan do not accept the Indian claim. There are doubts about the very existence of the Instrument of Accession. The United Nations also does not consider Indian claim as legally valid: it recognises Kashmir as a disputed territory. Except India, the entire world community recognises Kashmir as a disputed territory. The fact is that all the principles on the basis of which the Indian subcontinent was partitioned by the British in 1947 justify Kashmir becoming a part of Pakistan: the State had majority Muslim population, and it not only enjoyed geographical proximity with Pakistan but also had essential economic linkages with the territories constituting Pakistan.”

India, a country dominated by the hated-Hindus, has forcibly denied Srinagar Valley’s Muslim majority over the years the freedom to become part of Muslim Pakistan – I stand here to be corrected but, in a nutshell, such has been and remains Pakistan’s official view and projection of the Kashmir problem over more than sixty years.[13]

Part II

-

India’s Point of View: British Negligence/Indifference during the Transfer of Power, A Case of Misgovernance in the Chaotic Aftermath of World War II

(a) Rhetoric: Whose Pakistan? Which Kashmir?

(b) Law: (i) Liaquat-Zafrullah-Abdullah-Nehru United in Error Over the Second Treaty of Amritsar! Dogra J&K subsists Mar 16 1846-Oct 22 1947. Aggression, Anarchy, Annexations: The LOC as De Facto Boundary by Military Decision Since Jan 1 1949. (ii) Legal Error & Confusion Generated by 12 May 1946 Memorandum. (iii) War: Dogra J&K attacked by Pakistan, defended by India: Invasion, Mutiny, Secession of “Azad Kashmir” & Gilgit, Rape of Baramulla, Siege of Skardu.

-

Politics: What is to be Done? Towards Truths, Normalisation, Peace in the 21st Century

The Present Situation is Abnormal & Intolerable. There May Be One (and Only One) Peacable Solution that is Feasible: Revealing Individual Choices Privately with Full Information & Security: Indian “Green Cards”/PIO-OCI status for Hurriyat et al: A Choice of Nationality (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran). Of Flags and Consulates in Srinagar & Gilgit etc: De Jure Recognition of the Boundary, Diplomatic Normalisation, Economic & Military Cooperation.

-

Appendices: