Surendranath Roy (1860-1929) helped pioneer Indian constitutionalism under several British governments: Carmichael, Ronaldshay, Lytton, the Simon Commission too.

Victor Bulwer Lytton (1876-1947) arrived as Governor in February 1922

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JrFpBLIedxw,

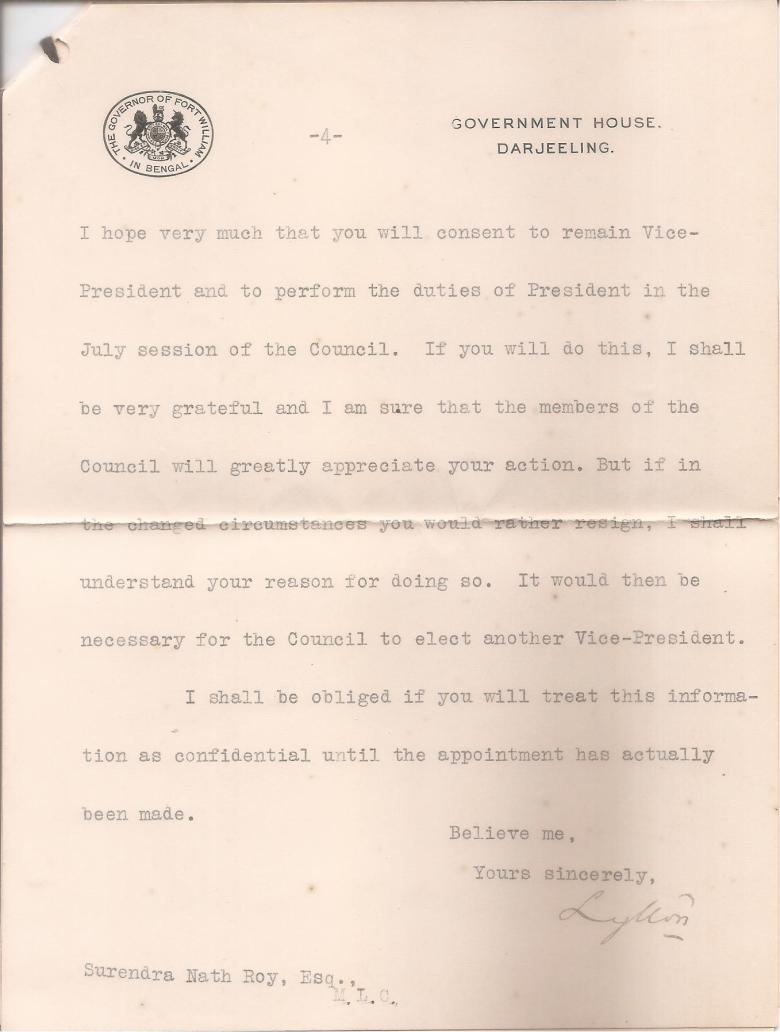

then in May wrote to SN Roy from Darjeeling.

Lytton’s letter below dated 1 May 1922 denied SN Roy appointment as President of the Bengal Legislative Council; Lytton imported HEA (Evan) Cotton (1868-1939) from England instead.

The purported reason Lytton gave was specious.

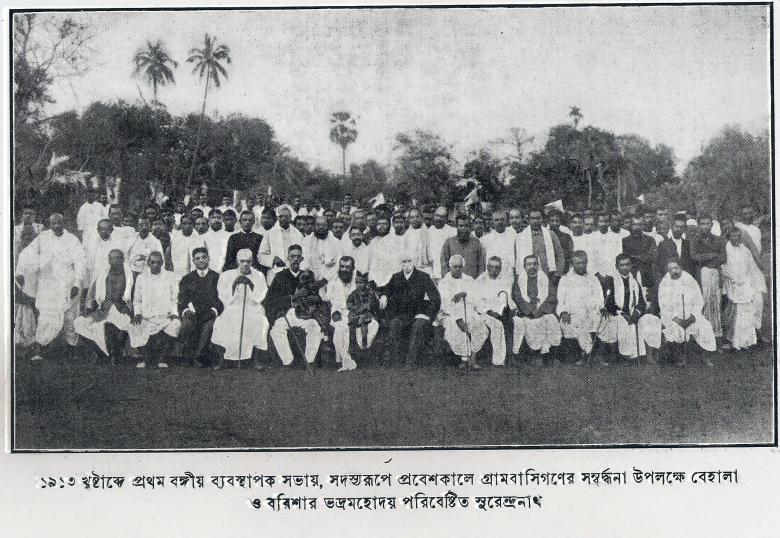

SN Roy had vastly more experience of Indian constitutionalism than Cotton. He had been the pioneering first President of an inchoate Bengal Legislative Council after the first 1912 elections, supported by the eminent British civil servant Sir Henry Cotton (1845-1915), who was Evan Cotton’s father!

The elder Cotton is seated to S N Roy’s left in this 1913 photograph of the newly elected members.

https://independentindian.com/2008/10/12/origins-of-indias-constitutional-politics-bengal-1913/

The younger Cotton, like S N Roy, had practised for some years as a lawyer in the Calcutta High Court, but then became a journalist and returned to England. There he apparently had a very minor political career, losing as a Liberal to Bonar Law in the 1910 General Election, being elected a London City Councillor as a Progressive until 1918, obtaining a parliamentary seat as a Liberal momentarily in a bye-election, then losing it again in a General Election.

During the same time, S N Roy had become the most influential officially recognised Indian statesman in Bengal, receiving as Deputy President the visit at home in 1916 of Carmichael, first Governor of Bengal after the 1912 reunification of Bengal,

https://independentindian.com/2009/03/01/carmichael-visits-surendranath-1916/

and later officiating for years as President of the Council under the next Governor, Ronaldshay (later a Secretary of State for India as the Marquess of Zetland).

https://independentindian.com/2009/02/28/bengal-legislative-council-1921/

SN Roy was what future historians would call a “Moderate” not a “Radical”: he pioneered primary education for the masses, became a legislative expert on local and general public finance as well as the federal politics of his time, authored books on the “Princely” States of Gwalior and Kashmir, and proposed the origins of what later became the Council of Princes and then the Council of States and then the Rajya Sabha. As early as 1888 in his book on Gwalior, SN Roy recommended popular Constitutions for India’s States on the grounds “where there are no popular constitutions, the personal character of the ruler becomes a most important factor in the government… evils are inherent in every government where autocracy is not tempered by a free constitution.”**

He protested the Salt Tax as early as 1918 in a speech to the Bengal Legislative Council; a decade later his idea may have been taken by his colleague KS Ray of Orissa to MK Gandhi in Gujarat.

In March 1919 Indian politics had been extremely tense over the draconian “anti-terrorist” law known as the Rowlatt Act. On 23 March, MK Gandhi called for the general strike or hartal on 6 April that later came to be known as the Rowlatt Satyagraha (and was soon to be followed by the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre in Amritsar on 13 April). On 28 March, MA Jinnah resigned his membership of the Viceroy’s Imperial Council in protest that the Rowlatt Act had not been amended as demanded by the Indian members of the Council. In midst of such tumultuous events, SN Roy on 27 March 1919 quietly managed to get his “Bengal Primary Education Bill” passed in the Bengal Legislative Council.

Evan Cotton like his father was a great friend of India — had Lytton not been prejudiced in his favour and against SN Roy as President, Cotton, the younger man by eight years and the less experienced of both constitutional politics and Bengal, may well have been happy to return from England to become SN Roy’s Deputy President. But that was not something Lytton’s racial consciousness could imagine: an Indian as Legislative Council President with a British Deputy President! There are analogies that may be easily found today in more recent cases of foreign rule.

Bengal politics and Indian politics from 1922 were marked by the rise of the Swaraj party of CR Das.

CR Das adopted obstructionism as a technique, much to Lytton’s displeasure, against the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms. SN Roy by contrast had in 1919 introduced with approbation in the Bengal Legislative Council the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms.

Cotton’s legislative tenure as President came to be rendered ineffective and dysfunctional by the Swarajists, as Lytton himself reported in *Pundits and Elephants* published in 1942, years after both SN Roy and Evan Cotton had died.

SN Roy had been a close political friend of CR Das, and may well have been able to find middle ground and guide Indian constitutionalism better after the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms in that tumultuous period.

The British aristocracy, like any other, was generally pompous but and incompetent. Lytton’s pompous incompetence as a governor in India was soon matched or surpassed by Linlithgow and of course Mountbatten.

Draft text 12 August 2018

** In a lecture to the Conference of State Finance Secretaries, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, 29 April 2000, I quoted SN Roy on the need for State Constitutions “We could ask if a better institutional arrangement may occur by each State of India electing its own Constitutional Convention subject naturally to the supervision of the National Parliament and the obvious provision that all State Constitutions be inferior in authority to the Constitution of the Union of India. These documents would then furnish the major sets of rules to govern intra-State political and fiscal decision-making more efficiently. An additional modern reason can be given… namely, that fiscal constitutionalism, and perhaps only fiscal constitutionalism, allows over-riding to take place of the interests of competing power-groups…” https://independentindian.com/2000/04/29/towards-a-highly-transparent-fiscal-monetary-framework-for-indias-union-state-governments/