Life of MK Roy 1915:2012, Indian Aristocrat & Diplomat, Birth Centenary Concludes 7 Nov 2016

MK Roy greeting the third of his great grandchildren… he died at age 96 three years later…

MK Roy greeting the third of his great grandchildren… he died at age 96 three years later…

MK Roy descended from Umbika Churn Rai (1827-1902) founder of the modern Roy family of Behala…

Umbik was a great grandson of Raja Daibaki Nandan Rai who is said to have brought the family to Behala from Anarpur at the time of the Mahratta invasions. Daibaki Nandan was probably gifted land at Behala as was customary towards Brahmins. The legend is that upon his arrival, a famed band of local dacoits or robbers gave him an ultimatum to surrender the family’s jewels or fight. Daibaki Nandan stood and fought, had his arm cut off by a scimitar, and died bleeding. The family then fell materially for two generations and were “toll pandits” or “tree-shade teachers” under Jagat Ram Rai and Durga Prasad Rai.

Umbik was a great grandson of Raja Daibaki Nandan Rai who is said to have brought the family to Behala from Anarpur at the time of the Mahratta invasions. Daibaki Nandan was probably gifted land at Behala as was customary towards Brahmins. The legend is that upon his arrival, a famed band of local dacoits or robbers gave him an ultimatum to surrender the family’s jewels or fight. Daibaki Nandan stood and fought, had his arm cut off by a scimitar, and died bleeding. The family then fell materially for two generations and were “toll pandits” or “tree-shade teachers” under Jagat Ram Rai and Durga Prasad Rai.

Umbik was Durga Prasad’s third son. He was a brilliant ambitious man, well-built over 6 ft tall, who taught himself English, ran away to attend the madrassa started by Warren Hastings to learn Persian, and was well-versed in Sanskrit…

Along with Hastings’s Madrassa came Hindu College too, also depicted as of 1847, which became in due course Presidency College…

Associated to Hindu College was Hindu School, and legend went Iswarchandra Vidyasagar (1820-1891) himself, took his friend Umbik’s eldest son Surendranath (1860-1929) by hand as a child to attend it.

Umbik, versed in Sanskrit, Persian and English at a time of conflict of laws between English, Muslim and Hindu systems, started as a translator in the Alipore Court under Sir Barnes Peacock (1810-1890).

When Peacock went to the new Supreme Court in Calcutta in 1859 as its first Chief Justice, Umbik (his nickname by Peacock) went with him and rose to become its first Chief Translator. He was made a Rai Bahadur at Victoria’s Jubilee. Rai Bahadur Road in Kolkata is named after him. The Golden Book of India published at the time of the Victoria Jubilee said Umbik was a descendant of one Raja Gajendra Narayan Rai, Rai-Raian, a finance official under the Great Mughal Jahangir.

Peacock returned to England in 1870 and later wrote asking Umbik and his eldest son for help on behalf of his own son, a lawyer, being sent to Calcutta from England. Surendranath, himself a noted lawyer by then, wrote back and assured Peacock he would help find his son work in Calcutta! Role reversal! Such was fin de siècle Bengal!

MK Roy’s grandfather, Surendranath, had a deep impact on his life, values and culture.

Surendranath was an eminent statesman of his time, a pioneer of constitutional progress in India, sometime President of the Bengal Legislative Council, a close political friend of CR Das who led the Indian National Congress before MK Gandhi, as well as of JC Bose and Ashutosh Mukherjee.

This 1913 photograph is of Indian members of the first Bengal Legislative Council elected in 1912 after the 1909 Morley-Minto reforms; the members apparently were being greeted by gentlemen of the sub-urban areas south of Calcutta. The Englishman in the middle seems to be Sir Henry Cotton (1845-1915), 1904 President of the Indian National Congress and a great political friend of India. To his right sits Surendranath who may have been the Council’s first President. By way of incidental reference, the young Jawaharlal Nehru had returned from his studies in England in 1912; MK Gandhi was still in South Africa and would not be returning until 1915. The Tilak-Gokhale clash though had been in full swing since 1907. See also https://independentindian.com/2008/10/12/origins-of-indias-constitutional-politics-bengal-1913/

SN Roy was a pioneer of constitutional progress in India, a pioneer of primary school education, and a legislative expert on local and general public finance as well as the federal politics of his time, authoring books on the “Princely” States of Gwalior and Kashmir, and proposing the origins of what became the Rajya Sabha. He also protested the Salt Tax as early as 1918. SN Roy Road in Kolkata is named after him. The first photograph above is of him as a newly graduated advocate, the second may have been after his book on Gwalior was published in 1888. He also gave the Tagore Law Lectures in 1905, on the subject of customary law; these are available at India’s National Library.

Carmichael, first Governor of Bengal after the 1912 reunification of Bengal and East Bengal, paid a 1916 visit to Surendranath’s home at Behala, Surendranath then Deputy President of the new Bengal Legislative Council and probably the most influential officially recognized political statesman in Bengal at the time. Surendranath’s younger son, Manindranath, father of MK Roy, is the bespectacled moustached young man in the middle holding a child.

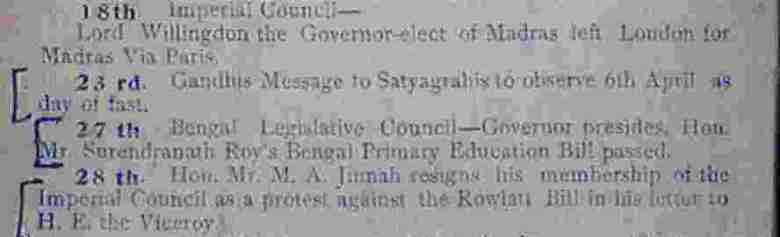

SN Roy had vastly more experience of Indian constitutionalism than Cotton. He had been the pioneering first President of an inchoate Bengal Legislative Council after the first 1912 elections, supported by the eminent British civil servant Sir Henry Cotton who was Evan Cotton’s father! The younger Cotton, like S N Roy, had practised for some years as a lawyer in the Calcutta High Court, but then became a journalist and returned to England. There he apparently had a very minor political career, losing as a Liberal to Bonar Law in the 1910 General Election, being elected a London City Councillor as a Progressive until 1918, obtaining a parliamentary seat as a Liberal momentarily in a bye-election, then losing it again in a General Election. During the same time, S N Roy had become the most influential officially recognised Indian statesman in Bengal. SN Roy was what future historians would call a “Moderate” not a “Radical”: he pioneered primary education for the masses, became a legislative expert on local and general public finance as well as the federal politics of his time, authored books on the “Princely” States of Gwalior and Kashmir, and proposed the origins of what later became the Council of Princes and then the Council of States and then the Rajya Sabha. As early as 1888 in his book on Gwalior, SN Roy recommended popular Constitutions for India’s States on the grounds “where there are no popular constitutions, the personal character of the ruler becomes a most important factor in the government… evils are inherent in every government where autocracy is not tempered by a free constitution.”** He protested the Salt Tax as early as 1918 in a speech to the Bengal Legislative Council; a decade later his idea may have been taken by his colleague KS Ray of Orissa to MK Gandhi in Gujarat. In midst of the tumultuous events of 1919, SN Roy on 27 March quietly managed to get his “Bengal Primary Education Bill” passed in the Bengal Legislative Council.

Evan Cotton like his father was a great friend of India — had Lytton not been prejudiced in his favour and against SN Roy as President, Cotton, the younger man by eight years and the less experienced of both constitutional politics and Bengal, may well have been happy to return from England to become SN Roy’s Deputy President. But that was not something Lytton’s racial consciousness could imagine: an Indian as Legislative Council President with a British Deputy President! There are analogies that may be easily found today in more recent cases of foreign rule. Bengal politics and Indian politics from 1922 were marked by the rise of the Swaraj party of CR Das who adopted obstructionism as a technique, much to Lytton’s displeasure. Cotton’s legislative tenure as President came to be rendered ineffective and dysfunctional by the Swarajists as Lytton himself reported in *Pundits and Elephants* published in 1942, years after both SN Roy and Evan Cotton had died. SN Roy had been a close political friend of CR Das, and may well have been able to find middle ground and guide Indian constitutionalism better in that tumultuous period. Lytton’s pompous incompetence as a governor in India was soon matched or surpassed by Linlithgow and of course Mountbatten.

It was not known until recently SN Roy was present and badly injured, along with Ardeshir Dalal, by Bhagat Singh’s bomb thrown in the Central Legislative Assembly on 8 April 1929 during the Simon Commission deliberations. SN Roy died seven months later on 11 November, plunging the Roy family into chaos it never recovered from.

MK Roy’s father Manindranath (1891-1958) was a quiet enigmatic literary figure and artistic benefactor in Calcutta; he wrote very well and had excellent taste and manners, though was of foolish judgement in money and friends.

The photograph below is from about 1922 at Allahabad where Manindranath used to take his family on annual holiday. The little boy to the left behind his mother would grow up to become my father, MK Roy. Manindranath is dressed in fine post-Edwardian fashion; at the time, his father Surendranath was at the peak of his political career as first Deputy President and then President of the new Bengal Legislative Council. Surendranath was an orthodox Brahmin and chose never to wear Western-style suits and neck-ties, and he was thoroughly averse to the idea of dining with Europeans. Manindranath was the first to wear Western clothes, as well as to dine in Calcutta’s Western restaurants. There was tension between father and son due to such matters. Surendranath could have easily sent his son to England to become a barrister but that would have seemed untoward favouritism by a public figure of his stature in Bengal politics.

MK Roy’s mother Nirmala Debi, 1900-1976, was a famed beauty of Uttarpara. She was married at age 9 to her husband who was 18, but the story went her mother-in-law slept between the couple for four years as he was constantly teasing her and pulling her hair. Finally the mother-in-law must have departed and she gave birth to her first son at age 13 and to my father at age 15.

MK Roy, seated, with his older brother Probhat about 1919.

Manindranath might have bullied his wife into posing for the risque photo above; his orthodox father would have almost certainly disapproved and forbidden it had he known.

Manindranath again in a photo with his wife that his father would have disallowed. In the days before radio, Bengali society had literature and the arts to keep itself company (besides politics). Writing and reading poetry was a common hobby. Three principal literary journals were Bharatvarsha, Probasi and Bichitra. The long-standing editor of Bharatvarsha was Jaladhar Sen, and it was he who had introduced Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyaya to Manindranath when Sarat had returned (in impecunious circumstances) to Bengal from Burma, probably with a request that Sarat be supported and sponsored. We made a literary find a few years ago: a notebook of Manindranath’s that he had titled Mandakini. It contains some 51 poems and poetic songs composed between 1914 and 1936, from when he was aged about 23 to when he was 45. No one knew of the existence of these poems until recently. Nor had he told anyone of the work, perhaps because some of the poems are especially candid; his affairs of the heart outside his marriage were said to be notorious. Between about 1933 and 1943 Manindranath found himself facing trials and tribulations of such gravity and magnitude (caused by his having trusted a crooked cunning uncle and others, foolishly squandering within a few years his vast inheritance from his father) that he may have wished to forget, ignore or even regret his creative period. Many of the poems are recorded as having been published in literary journals of the time, like Bharatbarsha and Bichitra, and some are recorded as having been sung or performed on the new radio service of the time, especially around 1931…

MK Roy with his older brother Probhat and younger sisters Madhuri and Manushi, with their grandfather Surendranath c. 1927, on the front-terrace of the house Surendranath built c. 1926.

I was surprised when he told me a few years ago he and his brother and cousins all wore dhotis right through college days. The sofa-chair is part of a set we use every day today.

This is a 1928 photo of the male members of the Roy Family of Behala, south of Calcutta, along with the children. Adult women would have been behind an effective “purdah”. The bearded patriarch in the middle is Surendranath; Manindranath, is seated second from right in the second row with spectacles and moustache. In the next year 1929, Surendranath and Ardeshir Dalal would be the only two casualties of Bhagat Singh’s bomb, and he would die some months later, throwing the Roy family into chaos it never recovered from.

The bright lad fourth from the left in the last row would grow up to be my father.

College days and then his first jobs, first with the Indian Oxygen and Acetylene Company (he knew nothing at all about chemistry), and then with the Tata Steel Company:

There seem to be large oxygen cylinders in the background of the picture at the top. He once told me that one came crashing down from a higher floor once and missed him by inches. That would have been the end of him, and our stories would not have begun at all. The lower photograph may have been with Indian Oxygen or the Tatas…He is standing dressed in a dapper cream double-breasted suit with a flower in his lapel-button it would seem; it suggests from his suit that the photo was dated 1936 at the Tatas, as that is written at the back of a previous photo in the same suit. Also, c 1937, posing with a friend outside the new Central Legislative building in New Delhi, which would later become India’s Parliament.

MK Roy visits Darjeeling, 1934, a guest of family friend Sir BP Singh Roy, second from left.

MK Roy visits Darjeeling, 1934, a guest of family friend Sir BP Singh Roy, second from left.

MK Roy married on 11 May 1942 during the war, with the Japanese bombing Calcutta. Soon thereafter he joined the Government of India for the first time in the war-time Ministry of Supply.

The 1940 Lahore Resolution of the Muslim League did not mention the word “Pakistan” but is considered its political blueprint. MA Jinnah’s political support lay among the Muslim elite in Muslim-minority areas of India — he needed a show of support from the Muslim-majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal too, and indeed Sikandar Hyat Khan and AK Fuzlul Huq came to draft and present the Lahore Resolution. Fuzlul Huq was Prime Minister of undivided Bengal from 1937-1943. Fuzlul Huq, having been a young colleague of Surendranath in the Bengal Legislative Council, was a family friend and treated Manindranath with affection. (Manindranath was a Justice of the Peace, but unlike his father was not political.) On 11 May 1942, Fuzlul Huq led the bridegroom’s procession when MK Roy went to wed my mother. Here he is above with his friend Manindranath helping him into the car. My mother’s family were surprised; they were Brahmins from Jamshedpur and did not quite know what to make of all this. My mother, aged 16 at the time, remembers she was non-plussed to find Fuzlul Huq ‘s bulky frame seated for some reason between her and her new husband in the car on the return journey too!

Fuzlul Huq would apparently make requests of Nirmala Debi for delivered meals during political confabulations; Manindranath’s family had been forced to leave Behala as the family home had been requisitioned by the military to be a hospital during the war, and they lived instead at 14 Hindustan Park in Ballygunge. MK Roy recalled cycling from there with the requested food to Fazlul Huq’s political confabulations in the middle of the wartime blackout (Japanese aeroplanes had apparently reached Calcutta on their bombing missions). The note dated 9 August 1945 from Fuzlul Huq to Manindranath thanks him for food sent and sends his “best blessings” to my grandmother — a Muslim, one of the founders of Pakistan, sends his blessings to an orthodox Hindu Brahmin family and everyone remains completely cheerful and apolitical: such was normal Indian secularism in practice at the time. Partition between India and Pakistan and the ghastliness that accompanied it, and the hatred and bloodshed that has followed, were all quite beyond anyone’s imagination at the time.

My parents and their eldest child Suchandra (Buju), about 1945-1946 on their way to Karachi where MK Roy was sent to head a Ministry of Supply office while handing it over to the new Pakistan.

After several months in Karachi, MKRoy sent his wife (pregnant with their second child) back to Bombay when anti-Hindu slogans (Hindu ko maro) had started to appear on the walls. This is a photo of him (in white dinner jacket) at the Karachi Club 1946 probably Christmas. MK Roy was one of the few Government of India officers in Karachi attending the inauguration of the new Pakistan on 14 August 1947: he went dressed in khakis with a holstered revolver too, riding on a bicycle, accompanied by two liveried orderlies also on bicycles.

MK Roy, one of the last Government of India officers left in Karachi, was asked by his clerk, one Lalwani, to visit the Karachi port area to see the plight of masses of Hindu Sindhis, living in extreme fear as Karachi heard rumblings of Pashtun plans to conduct a massacre and abduct women, as had happened in Punjab and elsewhere. The masses were huddled and camped out on the main road near the port fearing massacre and abduction, the women dressed in black burkhas; Lalwani took MK Roy around the area and begged him to do something. Returning from Karachi to Delhi on a British London-Singapore flight, MK Roy was met at Palam airport by his cousin Kanjilal, who accompanied him in a lorry through streets littered with dead from the riots, to see Shyama Prosad Mookherjee, his Minister. Mookherjee had been a family friend and knew him well, MK Roy reported what he had seen in Karachi; Mookherjee told him to prepare a note for the morning which he would put up to the Nehru Cabinet. MK Roy did so overnight, dictating to a typist, Mookherjee put the note to the Nehru Cabinet in the morning; Nehru immediately ordered dispatch of three frigates from Bombay to Karachi for a safe evacuation of the refugees… There was no massacre or abduction of women among the Hindu Sindhis in Karachi….The Hindus were evacuated safely over time. (LK Advani, Rajnath Singh et al may note the cooperation of Nehru and Shyama Prosad.)

As it happened, MKRoy had been a young colleague and friend at the Tatas of Zafrullah Khan’s younger brother Amanullah? Abdullah? Khan; when MK Roy had applied to join the Government during World War II in 1942, the brother introduced him to his illustrious older brother who was then perhaps Dewan of Bhopal. MK Roy visited Zafrullah at home in Delhi and the latter took a liking to him, invited him to dine together many times and to walk in the Lodhi Gardens every day. Some five years later, in late August or early September 1947, they met again at Karachi Airport when MK Roy was about to depart for Delhi. Zafrullah was on his way to New York to argue Pakistan’s case as Ambassador. “What are you doing here? Where are you going?” he demanded of the younger man. “Join us”, he told him, suggesting MK Roy stay in the new Pakistan. MK Roy fibbed saying he was going to Delhi to get his wife and family but in fact he was politely declining the offer. When he got to Delhi, he was met by his cousin Kanjilal at the airport, and then headed to make his report to his Minister, Shyama Prosad Mookherjee, about the situation of the Sindhis.

Nehru and Shyama Prosad, thanks to the young officer’s information, managed to save the Hindu Sindhis of Karachi from massacre and abduction huddled defenceless in fear in the port area. The young officer’s name came to be known in the small political and official world of Delhi at the time, and by way of reward perhaps, the Mountbattens themselves came to invite him on 13 January 1948 and Prime Minister Nehru himself invited him on 20 June 1948 in the official farewell to the Mountbattens.

MK Roy never sought to use the event to his advantage in his later career as a diplomat in the new Indian Foreign Service.

As of 1952 MK Roy was in Bombay as Deputy chief Controller Imports & exports, soon headed in 1954 to Tehran as the first Trade Commissioner at the Indian Embassy. His wife and daughters in their Bombay flat…

In March 1954, MK Roy and his family sailed from Bombay for Iran, posted as India’s first Trade Commissioner in Tehran, under the ambassadorship of the great Allahabad University historian and educationist Dr Tara Chand.

Within days of his arrival, he went on tour to Baghdad, Damascus, Jerusalem, Cairo, Beirut, all placed for purposes of trade and commerce with India within his ambit as Trade Commissioner: that whole region, since torn asunder by war and conflict, was very much a single economic zone as of the early 1950s.

On the reverse of this photo below is stated the date, 8 July 1955, and “the King enquiring about Indian development projects after the ceremony”. The person he is talking to is MK Roy, then India’s Trade Commissioner in Tehran. The two photos below show Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlevi striding by a line of guests (my father is seventh from the right in the line-up) and then meeting them.

The photos above include Reza Shah and his Queen Soraiya Esfandiary being greeted by a senior Sikh member of the Indian community. They had returned from abroad and the small community of diplomats, officials, and public persons were expected to attend to their arrival. Others in the photos above include Dr Tara Chand, the young MP Birla who with his wife Priyamvada Birla became friends of MK Roy and his wife since, also possibly the young SP Hinduja (dressed in a smart double breasted suit, holding a briefcase). Iranian Prime Minister Ala descending the stairs at the Indian Embassy in Tehran with Dr Tara Chand is in the photo above. This is an ongoing album which will be added to.

The family had a new addition in Tehran, myself:

MK Roy’s good work in Tehran earned him a new transfer to Ottawa, where he was First Secretary and Trade Commissioner, and was also concurrently asked to open a consulate in Vancouver.

Suez was closed due to war, and the family travelled on the Polish vessel Batory (the Captain has me popping up just above the tablecloth) from Bombay, to Karachi to Mombasa, around the Cape of Good Hope, up through the Canary Islands, to Southampton… After a week in London for the first time, the family was en route to the New World on Cunard’s Ivernia:

On the Ivernia, my mother learnt a philosophical something from a butler onboard: she had asked for something from the harried butler in the cold February Atlantic, and he had snapped back at her saying “One thing at a time”: a slogan she used throughout her life, and which I must have inherited too.

At 73 Riverdale Avenue in Ottawa in May 1957, MK Roy placed his son down and took this photo of his toddler (yes I faintly recall it happening).

Manindranath Roy, though in poor health, decided to visit his second son’s family in Ottawa in 1958. He did so and had a happy summer there.

I was routinely pumelled in the grass by a bigger tougher neighbour and best friend Richard Landis: I recall Manindranath being disconcerted watching this after his walks, tapping his walking stick on the pavement and telling me in agitation “Dadu, merey dao, tumi o merey dao”.

But Manindranath died in Ottawa on 2 September 1958 at Civic Hospital, apparently the first Hindu gentleman to have done so: there was no place to cremate him in Ottawa, and we had to drive to Montreal for that.

From Canada, MK Roy was going to be transferred in 1960 to the highly sensitive post of Peking/Beijing on the political side; our family was shocked. He asked to be transferred nearer India or back home if possible as he had growing daughters and his elder daughter was nearing marriageable age and he had other problems relating to Manindranath’s passing. He was sent first to Ceylon, then to East Pakistan.

Return to Hindustan Park…

Buju’s wedding…

MK Roy’s 1965 War leadership was such he was much commended by M A Husain, Secretary in the Foreign Ministry in Delhi (whose own brother or cousin happened to the Pakistan envoy in Delhi during the war)! MK Roy’s name was mentioned for the Padma Shri (an exceptional honour for a serving civil servant at the time) for his leadership in Dhaka during the war — for some reason, probably bureaucratic viciousness among his colleagues, he did not get it. But he was rewarded: with splendid Stockholm!

Stockholm was where MK Roy gave his younger daughter in marriage in a resplendent Vedic ceremony fifty years ago. Tunu married an Indian graduate of Stockholm Tekniska Institute, who became a Sales Engineer at ASEA & took her to live at Parstugugatan in Vasteros…

Important roles followed in Odessa, and especially Paris in 1971 during Indira Gandhi’s visit trying to prevent the Bangladesh war. PN Haksar himself sent him, asking him in Delhi “Can you go to Paris?” — a rhetorical question if ever there was one. In Paris, the emerging Bangladesh loomed high, both with defecting East Pakistani diplomats and the visiting Bangladesh Government-in-Exile, as well as with air-lifting French aid for the refugees from the Pakistani atrocities. In Paris too I recall Kewal Singh, then ambassador in West Germany, visiting us, and as soon as Kewal Singh became Foreign Secretary, MK Roy went as ambassador to Helsinki, his last appointment as a diplomat: a productive exciting career that had commenced in Tehran, Ottawa and Vancouver, and Colombo, before the war experience in Dhaka.

In retirement back home, he did not realise how Indian society had changed during his decades away. The old noblesse oblige he had been used to was all long gone, and a cunning age of calculators and yes sophisters had succeeded.

Comments Off on Life of MK Roy 1915:2012, Indian Aristocrat & Diplomat, Birth Centenary Concludes 7 Nov 2016

MK Roy greeting the third of his great grandchildren… he died at age 96 three years later…

MK Roy greeting the third of his great grandchildren… he died at age 96 three years later… Umbik was a great grandson of Raja Daibaki Nandan Rai who is said to have brought the family to Behala from Anarpur at the time of the Mahratta invasions. Daibaki Nandan was probably gifted land at Behala as was customary towards Brahmins. The legend is that upon his arrival, a famed band of local dacoits or robbers gave him an ultimatum to surrender the family’s jewels or fight. Daibaki Nandan stood and fought, had his arm cut off by a scimitar, and died bleeding. The family then fell materially for two generations and were “toll pandits” or “tree-shade teachers” under Jagat Ram Rai and Durga Prasad Rai.

Umbik was a great grandson of Raja Daibaki Nandan Rai who is said to have brought the family to Behala from Anarpur at the time of the Mahratta invasions. Daibaki Nandan was probably gifted land at Behala as was customary towards Brahmins. The legend is that upon his arrival, a famed band of local dacoits or robbers gave him an ultimatum to surrender the family’s jewels or fight. Daibaki Nandan stood and fought, had his arm cut off by a scimitar, and died bleeding. The family then fell materially for two generations and were “toll pandits” or “tree-shade teachers” under Jagat Ram Rai and Durga Prasad Rai.

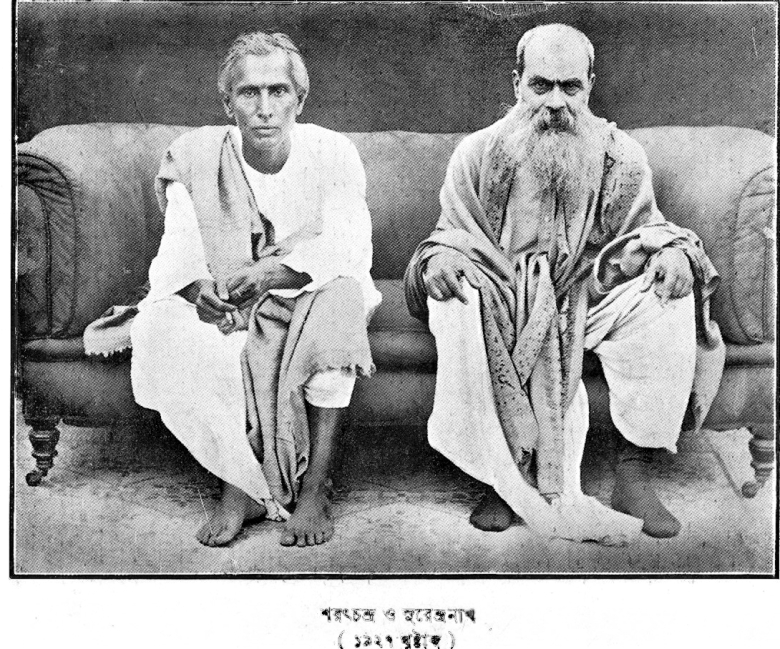

Saratchandra visits Surendranath (they are seated on a sofa still in use today). See too https://independentindian.com/2008/10/12/sarat-writes-to-manindranath-1931/ https://independentindian.com/2009/02/23/jaladhar-sen-writes-to-manindranath-at-surendranaths-death-c-nov-dec-1929/

Saratchandra visits Surendranath (they are seated on a sofa still in use today). See too https://independentindian.com/2008/10/12/sarat-writes-to-manindranath-1931/ https://independentindian.com/2009/02/23/jaladhar-sen-writes-to-manindranath-at-surendranaths-death-c-nov-dec-1929/

MK Roy visits Darjeeling, 1934, a guest of family friend Sir BP Singh Roy, second from left.

MK Roy visits Darjeeling, 1934, a guest of family friend Sir BP Singh Roy, second from left.