On the rot of institutions (and what an Academy might be like in the Facebook/Internet Age): Listening to the ladies….

August 31, 2011 — drsubrotoroyThere is hardly anything of deep significance involved except it gives the lie to all the government and elite propaganda about how well India is doing — and in that context becomes relevant too what I did in America which came to Rajiv Gandhi through my advice to him in his last months

Excuse me, but statistically the number of deaths and infections in India from swine-flu is, hmmm, zero: Time for rationality please!

August 13, 2009 — drsubrotoroyWhy are the government and media spreading panic in India about swine-flu? There is almost none of it.

The population of India as of August 2009 is near 1,163,698,689.

Something between 19,782,878 and 115,206,170 people among this population may be suffering some kind of ailment or other at any given time (don’t forget headaches, runny noses, upset tummies, sore backs etc). The lesser figure comes by taking the minimum rate of morbidity across regions, 17/1000, the greater figure comes by taking a supposed national average morbidity rate of 99/1000. I shall be happy to yield to more accurate figures from any source.

Of these millions, some 1,200 (twelve hundred) are said to have been isolated due to and are being treated for swine-flu as of today. That is, statistically speaking, zero.

As for deaths, India experiences something between 20,405 and 26,398 deaths per day from all causes, depending on whether you use 6.40/1000 or 8.28/1000 as the mortality rate.

The number of deaths in India attributed to swine-flu since August 3 is twenty — or about 2 per day on average. That again is, statistically speaking, zero.

Of course governments at Union and State levels and the public health authorities and medical authorities need to follow their protocols and procedures – for swine-flu and every other disease that afflicts us. But, please, closing down cities and towns or holding so many ministerial meetings due to a purported swine-flu epidemic in the country is quite simply a nonsensical waste of resources. Time for a little rationality please.

Subroto Roy

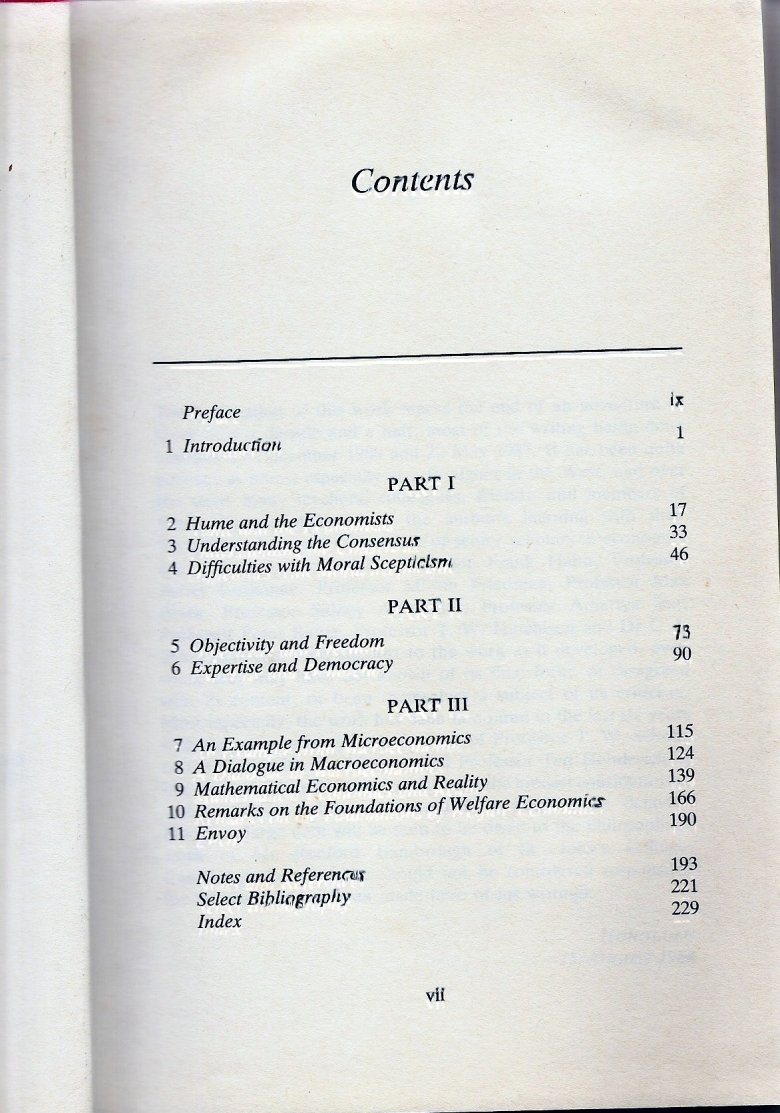

Apropos *Philosophy of Economics*

April 22, 2009 — drsubrotoroyfrom Twitter 10 September 2017:

What is the precise scientific claim of my book *Philosophy of Economics* (Routledge 1989) to the Sverige Riksbank Economics Nobel prize? It is that I detected & corrected central errors in the work of Hicks and Arrow, two greats of 20thC economics, who were early winners in 1972…. And both Hicks and Arrow graciously agreed to my criticism… perhaps even admitted the errors…

Three other early winners, Hayek 1974, Friedman 1976, Schultz 1979, supported my work even more strongly: the last two stood as witnesses! Yes #BankofSweden @NobelPrize I bet you didn’t know your early winners Friedman 1976 Schultz 1979 testified on my behalf in US Federal Court!

So I end up using Twitter to say all this? Yes… ongoing battles against racism in America, corruption in India…!

It is thanks to the Internet my 1989 *Philosophy of Economics* survived the vicious attack against it in America…And Sidney Alexander, contemporary of Samuelson, teacher of Solow, in 1985 found an ally in my work…Alexander and I were pirate ships blowing holes in the positivist Armada of “social choice theory” etc, sinking it permanently…

The incoherence confusion dogmatism irrelevance of a lot of academic economics today dissipates thanks to my 1989 Philosophy of Economics. If #BankofSweden @NobelPrize wants to reduce the incoherence of economics let it read the Zinn review below in German & English

Apropos *Philosophy of Economics*

“Dr. Roy’s book, Philosophy of Economics, which I have read in galleys, I regard as a masterpiece, not only in economic analysis but in philosophic analysis as well.” — Sidney Hook 1989

“I shall have to ponder your rejection of the Humean position which has, I suppose, been central in not only my thought but that of most economists. Candidly, I have never understood what late Wittgenstein was saying, but I have not worked very hard at his work, and perhaps your book will give guidance.”–Kenneth J. Arrow, letter to the author, 1989

“I was grateful for the reminder of the passage of Aristotle at which I had not looked for many years and found the criticism of Arrow well justified and important.” FA Hayek, letter to the author, 1981

“It is an extraordinarily well-written and well-thought through book that shows a wide-ranging capacity and understanding of economics as a discipline in both its macro and micro aspects.” Milton Friedman 1991, Evidence in the US District Court for the District of Hawaii.

“There is no doubt whatsoever that he has a thorough and deep understanding of the major issues that have occupied macroeconomics over the past fifty years…. It is a sign of real understanding that Roy can state these ideas not in terms of jargon, not in terms of equations or technical terms, but in straightforward English using only a minimum of specifically economic terminology. All in all, it is a very knowledgeable and sophisticated performance.” — Milton Friedman, 1989

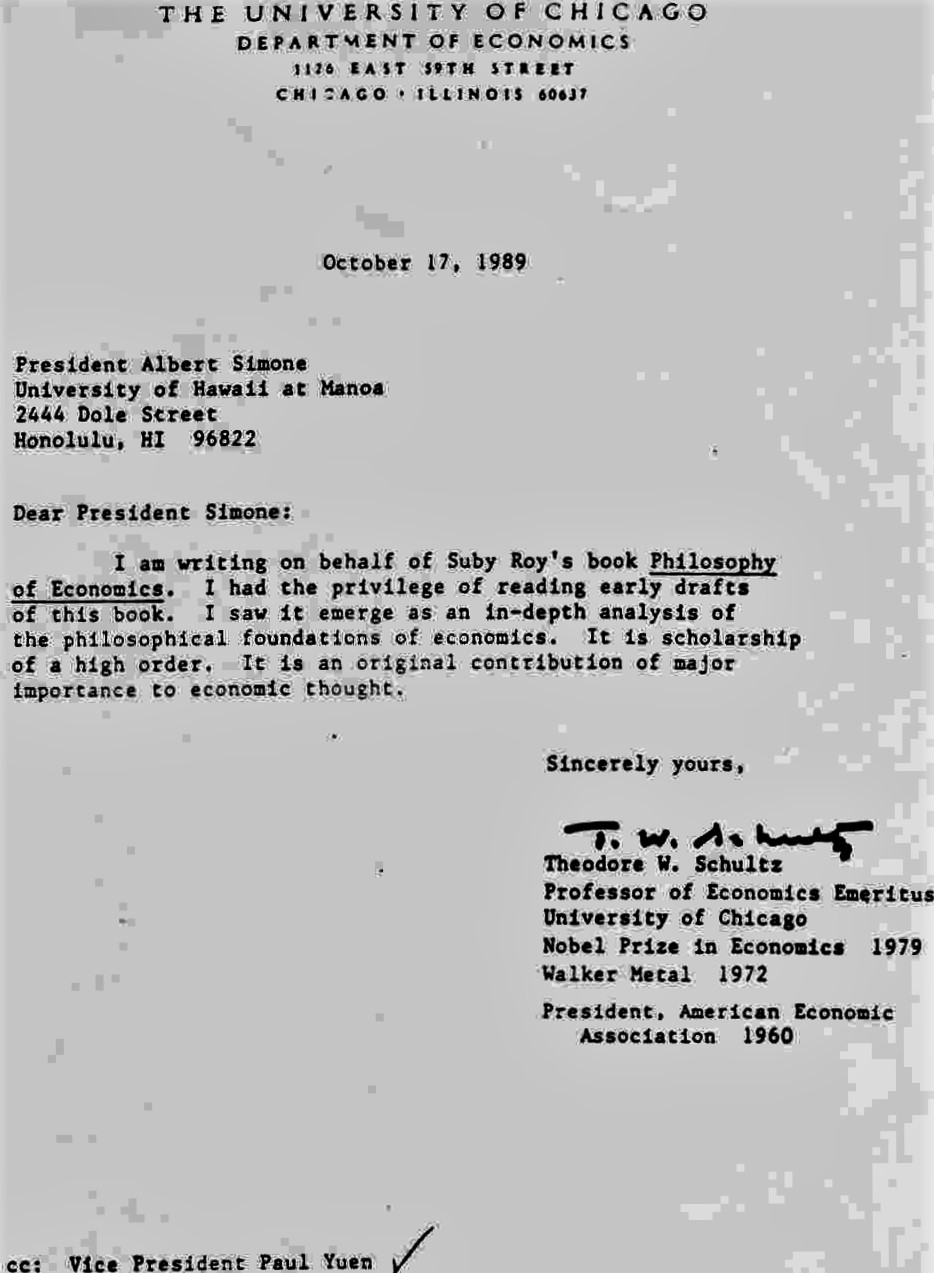

“I had the privilege of reading early drafts of this book. I saw it emerge as an in-depth analysis of the philosophical foundations of economics. It is scholarship of a high order. It is an original contribution of major importance to economic thought.” — Theodore W. Schultz 1989

“The core of Roy’s study is devoted to the nature and grounds of economics as knowledge; it examines the basic intellectual roots of economics. It is cogent and, what is exceedingly rare these days, it is refreshingly lucid…. Roy’s book is in several important respects an original contribution, the most important being his treatment of the philosophical foundations of economics as knowledge. He is all too modest in assessing the importance of his contribution.” Theodore W. Schultz, 1983

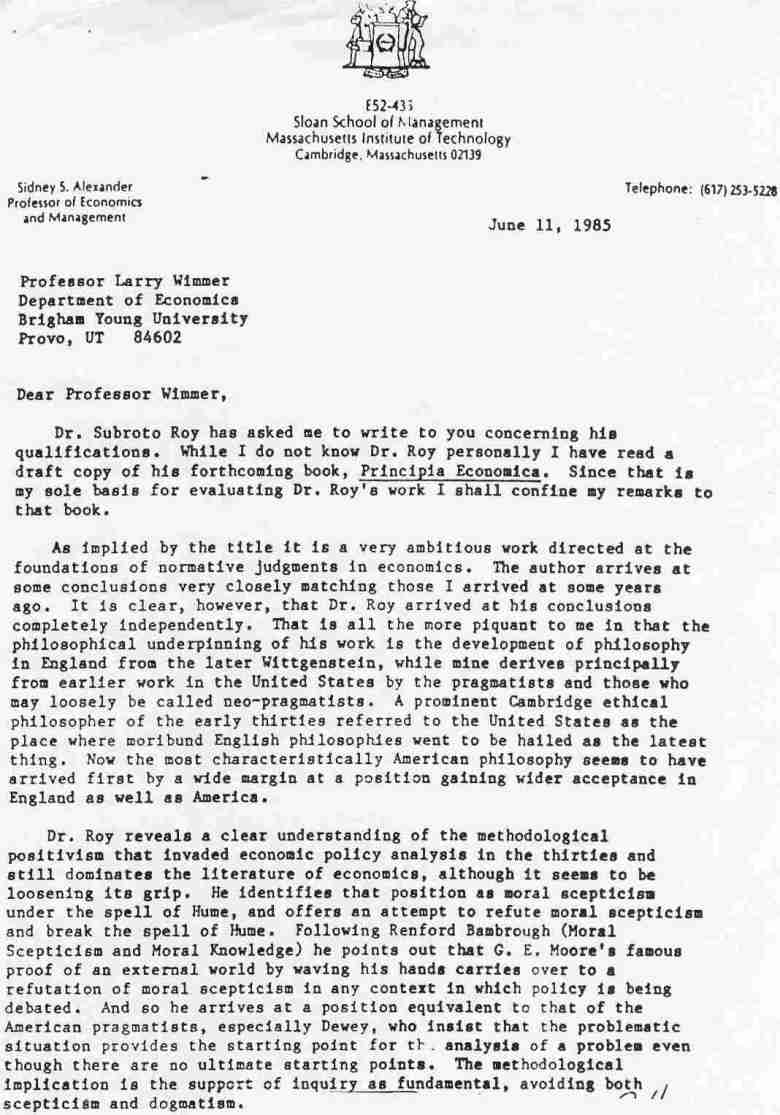

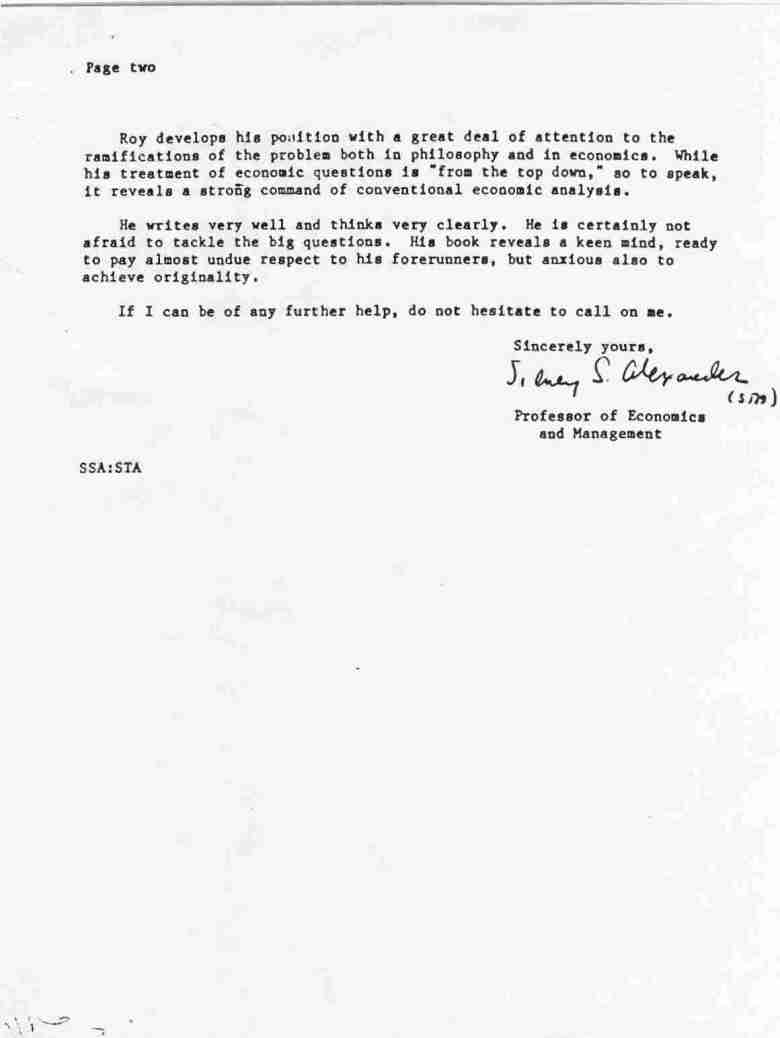

“ (This) is a very ambitious work directed at the foundations of normative judgements in economics. The author arrives at some conclusions very closely matching those I arrived at some years ago. It is clear, however, that Dr. Roy arrived at his conclusions completely independently. That is all the more piquant to me in that the philosophical underpinning of his work is the development of philosophy in England from the later Wittgenstein, while mine derives principally from earlier work in the United States by the pragmatists… Dr. Roy reveals a clear understanding of the methodological positivism that invaded economic policy analysis in the thirties and still dominates the literature of economics…. Following Renford Bambrough….he arrives at a position equivalent to that of the American pragmatists, especially Dewey, who insist that the problematic situation provides the starting point for the analysis of a problem even though there are no ultimate starting points. The methodological implication is the support of inquiry as fundamental, avoiding both scepticism and dogmatism. Roy develops his position with a great deal of attention to the ramifications of the problem both in philosophy and in economics. While his treatment of economic questions is ‘from the top down’ so to speak, it reveals a strong command of conventional economic analysis. He writes very well and thinks very clearly. He is certainly not afraid to tackle the big questions. His book reveals a keen mind, ready to pay almost undue respect to his forerunners, but anxious also to achieve originality….” Sidney S. Alexander, 1985

“I know that I have to continue to bear the responsibility for things that I wrote nearly fifty years ago. I am however glad that your attention has been drawn to that passage written much more recently….building up to what I think is a coherent point of view very different from that which I took in ’34 and ’39…. concerned with a field not far removed from that you reach…” John R Hicks, letter to the author, 1984

“A work altogether well written and admirably clear.” Renford Bambrough, 1985

“I like very much the courage in trying to produce a genuine philosophy of economics. Such a book is badly needed and could be very useful to economists. The fine use made of extensive readings in older as well as contemporary theorists and the splendid choice of quotations would themselves be worth the price of admission. The style maintains a fine level of clarity and emphasis.” Max Black 1985

“The discussion of Arrow’s theorem under unintended interpretations focuses our understanding on what is really fundamental to this famous result…. Roy has obviously thought much harder about the foundational and methodological problems in economics than most of his fellow-economists.” Anonymous

“Roy’s platonist view of what is the purpose of government is very odd at this stage of history. He seems to suppose that there is an objectively best state of affairs which we must simply discover. The more urgent issue in politics is generally not that of knowing what is the best thing to do but of dealing with conflicting interests. Conflict of interests is not merely disagreement over facts.” Anonymous

“The author has performed a very valuable service for economists interested in the philosophical problems and positions discussed. He has not misrepresented the positions he discusses and his account of various issues and different positions on those issues is philosophically adequate. Many economists will be stimulated as a result of reading this work to reconsider their own positions on the issues Roy addresses.” Anonymous

“The work has many strengths. It is wide in its references and its outlook. Its endorsement of objectivism is both right and timely. The chapter on mathematics in economics is particularly fine.” Anonymous

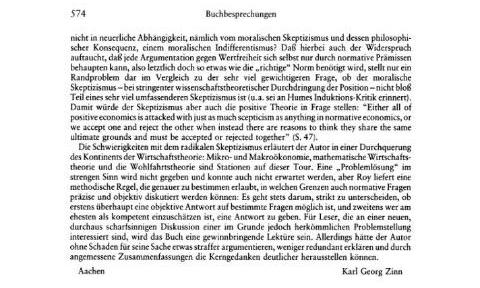

“The author intends to discuss some of the central philosophical questions facing modern economic theory. In the foreground is a disposition of the conventional problem of value-independence. Roy sees the value-independence postulate as “Hume’s Scepticism”. He defines Hume’s First and Second Laws on the basis of two signified propositions taken from R. M. Hare. (1) From positive empirical premises, no normative postulate can be derived; in order to establish obligatory propositions, at least one normative proposition is needed. (2) In a specified economic context, after all empirical and formal/logical matters are resolved, little scope exists for further intersubjectively valid answers. Valuations beyond this limit are based on the subjective feelings of the economist to the concerned problem. The scientific/theoretical attitude representative of most economists of the 20th century has been based on this characteristic Humean scepticism. To show this, the author reviews short representative quotations from some of the known names of recent economic theory: Friedman, Myrdal, Lionel Robbins, P. A. Samuelson, Hicks, Joan Robinson, Hayek, Oskar Lange, Schumpeter, Arrow, Blaug, Frank Hahn. Subsequently, the author raises the point as to what explains this scientific-theoretical approval. A cursory survey of important real and virtual historical developments since antiquity confirms that the essential reason for the reported wide acceptance of a humean position by the economic scientist indeed could have been as a defensive posture against dogmatism and political dictatorship (“It is part of the democratic reaction against medieval authoritarianism” p.45). Conditioned by their “disgust with the tyrannies and ideologies of the twentieth century”, these authorities tried to protect economic science and guarantee the objectivity of research by resort to moral scepticism. Hence the author arrives at the starting position of his actual subject: After using Hume to escape from dependence on Plato e tutti quanti, has not value-free economics gotten into a fresh dependence, namely, moral scepticism and its philosophical consequence, moral indifference? Here too a contradiction is shown to arise, namely, that each argumentation against the normative can stand its ground only through normative premises. Thus ultimately something like correct standards become necessary. This however is only a marginal problem compared to a very much more important point: whether the moral scepticism permeating the strict scientific-theoretical position, is not just part of a very much more comprehensive scepticism, which includes Hume’s own criticism of induction as well. But then the same scepticism makes positive theory dubious as well: “Either all of positive economics is attacked with just as much scepticism as anything in normative economics, or we accept one and reject the other when instead there are reasons to think they share the same ultimate grounds and must be accepted or rejected together”(p.47). The author illustrates the difficulties with radical scepticism in a continental traversal of economic theory: micro and macroeconomics, mathematical economic theory and welfare theory are stations on this tour. A solution of the problem in the strict sense is not given nor could have been expected. But Roy delivers a methodical rule which permits a more exact definition of the limits to which normative discussion can take place precisely and objectively: first, to distinguish always whether an objective answer is at all possible to certain questions, and secondly, to ask who is competent or in the best position to give an answer. For readers interested in a new, thoroughly subtle discussion of a basic yet customary problem, this book will be profitable reading. However, the author could have argued some matters slightly more elaborately and others less redundantly, and set forth the central idea more clearly through appropriate summaries.”

Karl Georg Zinn in Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik / Zeitschrift für Wirtschaft und Statistik. Vol. 209, Nr. 5/6 (May 1992), p 573-574, translated from the German by Nahar Bhattacharya 1994.

“Effectively demonstrates the direct and significant links between the basic philosophical beliefs held by economists and their fundamental disagreements” Kyklos (Switzerland).

“Every rule of good argument is flouted. Does little to grapple with the large issues to which he rightly urges us to attend.” Times Literary Supplement (UK).

“Not the book to set off the revolution in economic epistemology and it is not even a reliable introduction to the field for undergraduates.” Journal of Applied Philosophy (UK).

“Subroto Roy’s Philosophy of Economics is a formidable contribution…. The author’s aim is to steer a middle course between scepticism and dogmatism in his account of the knowledge we can have of economic phenomena, and in this he largely succeeds. The result is a most distinguished and valuable exploration of the nature of economic inquiry.” John Gray, Economic Affairs (UK).

“Interesting and well-written. Definitely worthwhile being read by any economist interested in the philosophical foundations of his subject and profession.”

Journal of Institutional & Theoretical Economics (Germany).

“Roy’s basic argument is that the theory of economic knowledge underlying the work of most economists is logically inconsistent… The inconsistency lies in not permitting the skepticism that undermines the analysis of normative problems to destroy the logical foundation underlying positive analysis….. This well-documented study is a worthwhile contribution to the burgeoning literature on the philosophy of economics.” Choice

“The central argument of the book shows that the skepticism/dogmatism choice is a false dichotomy, that one need not embrace dogmatism in order to have objectivity or give up objectivity for freedom…. In the final section of the book Roy applies his critique… to several debates in economics. Chapter 8 presents the development of macroeconomics from John Maynard Keynes to the present through a dialogue between economists of opposing schools… Chapter 9 is a rich, wide-ranging discussion of mathematical models in economics…. Chapter 10 discusses the foundations of welfare economics… Roy shows how philosophical mistakes can lead economic thought astray, even though some of his arguments are also unsound. As a philosopher I find it encouraging to see an economist apply recent developments in epistemology to economic debates.” Journal of Economic History

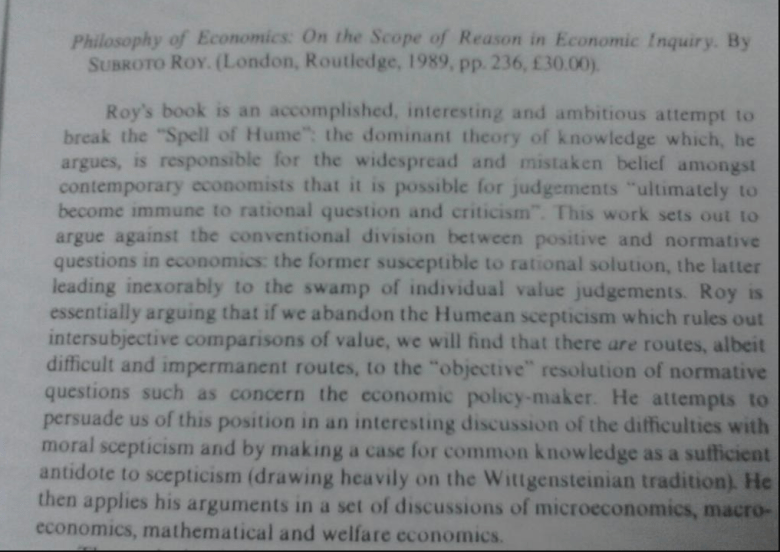

“Accomplished, interesting and ambitious.” Mary Farmer Manchester School (UK).

“Perfectly sensible.” De Economist (Netherlands).

“Engaging and illuminating study. His seamless style may lull the reader into underestimating the extent and difficulty of the philosophical ground covered.” Research in History & Methodology of Economics (USA).

“(Roy’s) message is for his fellow economists, urging them not to shy away from the treatment of normative issues in their discipline.” – Economics and Philosophy

“When Roy refers to the present received theory of economics, he means that this is the view not only of Chicago, but also of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Cambridge, England, of Friedman, Samuelson, Myrdal, Hayek, and Joan Robinson. His coverage is broad…. In one place he states that it is precisely because it is possible for even a unanimous group of experts to be wrong that we have a reason, an objective reason, why freedom is to be valued. ‘Freedom is necessary for objectivity.’…. Whether one agrees or disagrees, one has to be impressed by the knowledge and sophistication involved in Roy’s presentation. Involved here is no run-of-the-mill carping at the economics establishment. This is a serious thoughtful work.” Social Science Quarterly

My American years Part One 1980-90: battles for academic integrity & freedom

February 11, 2009 — drsubrotoroysee revised and expanded version

My American years: Part One 1980-90: battles for academic integrity & freedom

On the Blacksburg campus February 1982, my second year in America.

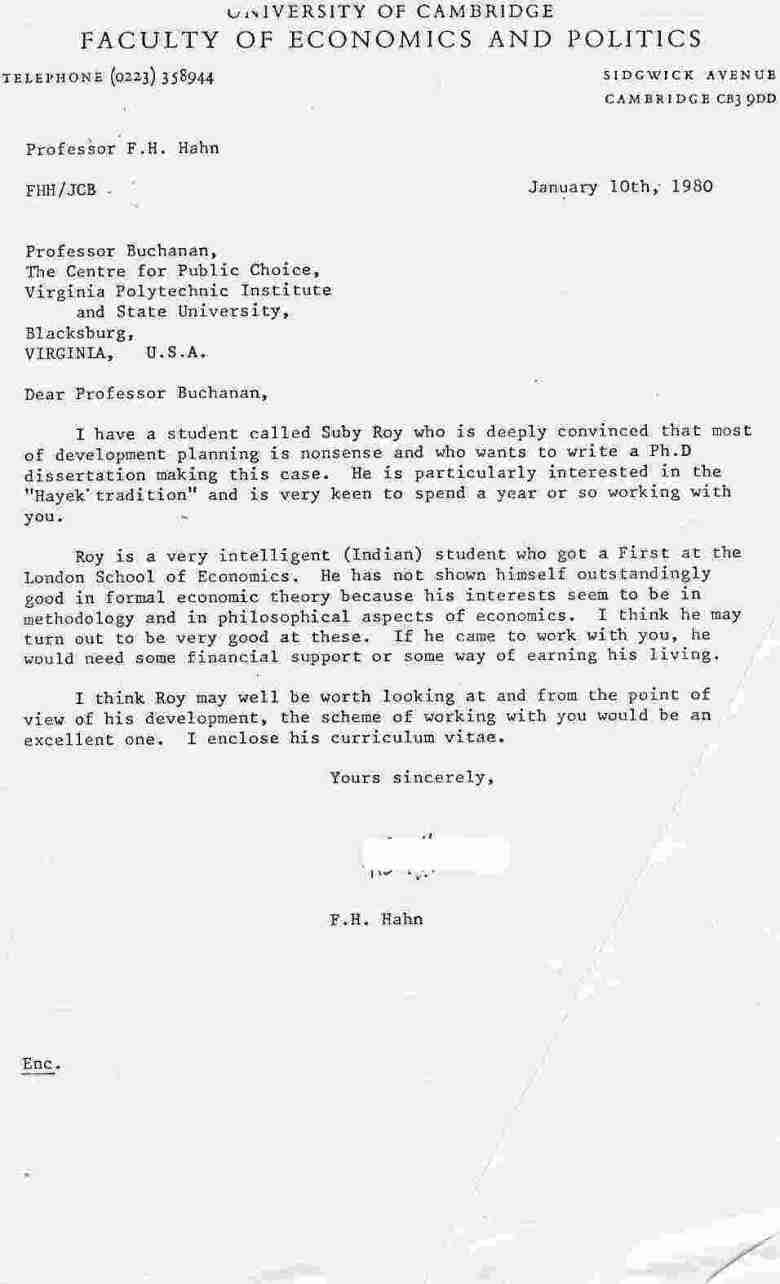

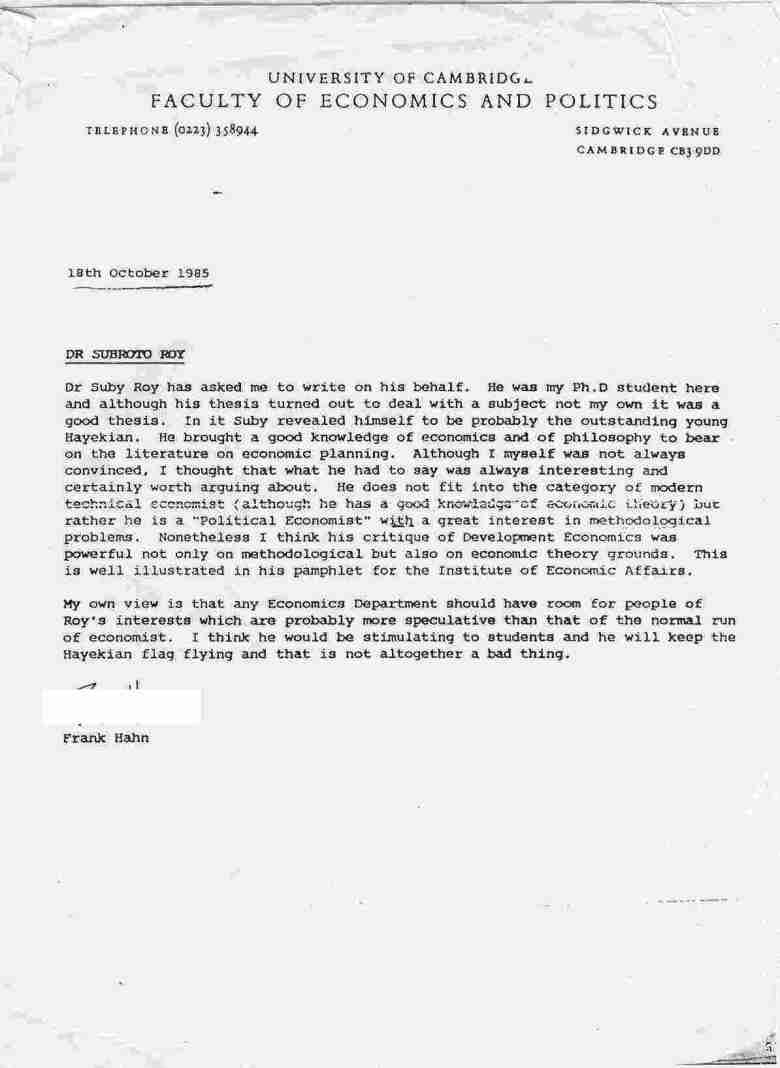

I had come to Blacksburg in August 1980 thanks to a letter Professor Frank Hahn had written on my behalf to Professor James M Buchanan in January 1980.

I was in an “All But Dissertation” stage at Cambridge when I got to Blacksburg; I completed the thesis while teaching in Blacksburg, sent it from there in September 1981, and went back to Cambridge for the viva voce examination in January 1982.

Professor Buchanan and his colleagues were welcoming and I came to learn much from them about the realities of public finance and democratic politics, which I very soon applied to my work on India.

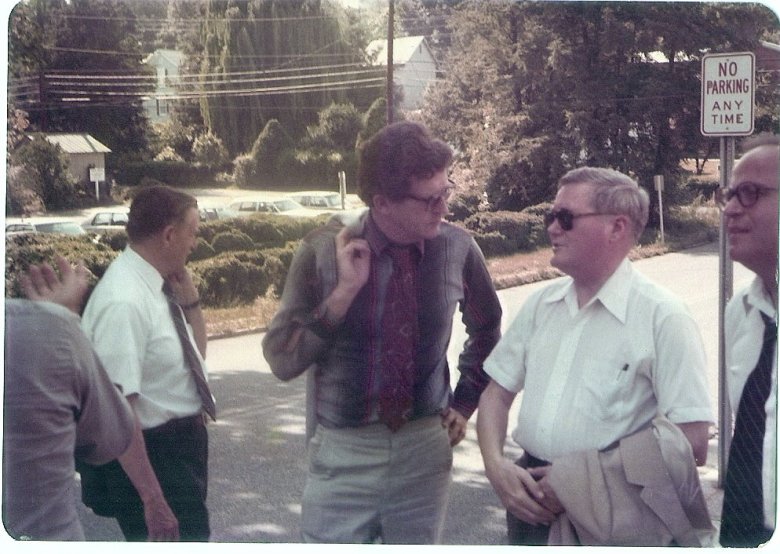

Jim Buchanan had a reputation for running very tough conferences of scholars. He invited me to one such in the Spring of 1981. We were made to work very hard indeed. One of the books prescribed is still with me, In Search of a Monetary Constitution, ed. Leland Yeager, Harvard 1962, and something I still recommend to anyone wishing to understand the classical liberal position on monetary policy. The week-long 1981 conference had one rest-day; it was spent in part at an excellent theatre in a small rural town outside Blacksburg. This photo is of Jim Buchanan on the left and Gordon Tullock on the right; in between them is Ken Minogue of the London School of Economics — who, as it happened, had been Tutor for Admissions when I became a freshman there seven years earlier.

(I must have learnt something from Jim Buchanan about running conferences because nine years later in May-June 1989 at the University of Hawaii, I made the participants of the India-perestroika and Pakistan-perestroika conferences work very hard too.)

My first rooms in America in 1980 were in the attic of 703 Gracelyn Court, where I paid $160 or $170 per month to my marvellous landlady Betty Tillman. There were many family occasions I enjoyed with her family downstairs, and her cakes, bakes and puddings all remain with me today.

A borrowed electric typewriter may be seen in the photo: the age of the personal computer was still a few years away. The Department had a stand-alone “AB-Dic” word-processor which we considered a marvel of technology; the Internet did not exist but there was some kind of Intranet between geeks in computer science and engineering departments at different universities.

It was at Gracelyn Court that this letter reached me addressed by FA Hayek himself.

Professor Buchanan had moved to Blacksburg from Charlottesville some years earlier with the Centre for Study of Public Choice that he had founded. The Centre came to be housed at the President’s House of Virginia Tech (presumably the University President himself had another residence).

I was initially a Visiting Research Associate at the Centre and at the same time a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Economics Department. I was very kindly given a magnificent office at the Centre, on the upper floor, perhaps the one on the upper right hand side in the picture. It was undoubtedly the finest room I have ever had as an office. I may have had it for a whole year, either 1980-81 or 1981-82. When Professor Buchanan and the Centre left for George Mason University in 1983, the mansion returned to being the University President’s House and my old office presumably became a fine bedroom again.

I spent the summer of 1983 at a long libertarian conference in the Palo Alto/Menlo Park area in California. This is a photo from a barbecue during the conference with Professor Jean Baechler from France on the left; Leonard Liggio, who (along with Walter Grinder) had organised the conference, is at the right.

The first draft of the book that became Philosophy of Economics was written (in long hand) during that summer of 1983 in Palo Alto/Menlo Park. The initial title was “Principia Economica”, and the initial contracted publisher, the University of Chicago Press, had that title on the contract.

My principal supporter at the University of Chicago was that great American Theodore W. Schultz, then aged 81,

to whom the Press had initially sent the manuscript for review and who had recommended its prompt publication. Professor Schultz later told me to my face better what my book was about than I had realised myself, namely, it was about economics as knowledge, the epistemology of economics.

My parents came from India to visit me in California, and here we are at Yosemite.

Also to visit were Mr and Mrs Willis C Armstrong, our family friends who had known me from infancy. This is a photo of Bill and my mother on the left, and Louise and myself on the right, taken perhaps by my father. In the third week of January 1991, during the first Gulf War, Bill and I (acting on behalf of Rajiv Gandhi) came to form an extremely tenuous bridge between the US Administration and Saddam Hussain for about 24 hours, in an attempt to get a withdrawal of Iraq from Kuwait without further loss of life. In December 1991 I gave the widow of Rajiv Gandhi a small tape containing my long-distance phone conversations from America with Rajiv during that episode.

I had driven with my sheltie puppy from Blacksburg to Palo Alto — through Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona; my parents and I now drove with him back to Blacksburg from California, through Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia. It may be a necessary though not sufficient condition to drive across America (or any other country) in order to understand it.

I had driven with my sheltie puppy from Blacksburg to Palo Alto — through Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico and Arizona; my parents and I now drove with him back to Blacksburg from California, through Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, West Virginia. It may be a necessary though not sufficient condition to drive across America (or any other country) in order to understand it.

After a few days, we drove to New York via Pennsylvania where I became Visiting Assistant Professor in the Cornell Economics Department (on leave from being Assistant Professor at Virginia Tech). The few months at Cornell were noteworthy for the many long sessions I spent with Max Black. I shall add more about that here in due course. My parents returned to India (via Greece where my sister was) in the Autumn of 1983.

In May 1984, Indira Gandhi ruled in Delhi, and the ghost of Brezhnev was still fresh in Moscow. The era of Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in America was at its height. Pricing, Planning & Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India emerging from my doctoral thesis though written in Blacksburg and Ithaca in 1982-1983, came to be published by London’s Institute of Economic Affairs on May 29 as Occasional Paper No. 69, ISBN: 0-255 36169-6; its text is reproduced elsewhere here.

It was the first critique after BR Shenoy of India’s Sovietesque economics since Jawaharlal Nehru’s time. The Times, London’s most eminent paper at the time, wrote its lead editorial comment about it on the day it was published, May 29 1984.

It used to take several days for the library at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg to receive its copy of The Times of London and other British newspapers. I had not been told of the date of publication and did not know of what had happened in London on May 29 until perhaps June 2 — when a friend, Vasant Dave of a children’s charity, who was on campus, phoned me and congratulated me for being featured in The Times which he had just read in the University Library. “You mean they’ve reviewed it?” I asked him, “No, it’s the lead editorial.” “What?” I exclaimed. There was worse. Vasant was very soft-spoken and said “Yes, it’s titled ‘India’s Bad Example’” — which I misheard on the phone as “India’s Mad Example” 😀 Drat! I thought (or words to that effect), they must have lambasted me, as I rushed down to the Library to take a look.

The Times had said

“When Mr. Dennis Healey in the Commons recently stated that Hongkong, with one per cent of the population of India has twice India’s trade, he was making an important point about Hongkong but an equally important point about India. If Hongkong with one per cent of its population and less than 0.03 per cert of India’s land area (without even water as a natural resource) can so outpace India, there must be something terribly wrong with the way Indian governments have managed their affairs, and there is. A paper by an Indian economist published today (Pricing, Planning and Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India by Subroto Roy, IEA £1.80) shows how Asia’s largest democracy is gradually being stifled by the imposition of economic policies whose woeful effect and rhetorical unreality find their echo all over the Third World. As with many of Britain’s former imperial possessions, the rot set in long before independence. But as with most of the other former dependencies, the instrument of economic regulation and bureaucratic control set up by the British has been used decisively and expansively to consolidate a statist regime which inhibits free enterprise, minimizes economic success and consolidates the power of government in all spheres of the economy. We hear little of this side of things when India rattles the borrowing bowl or denigrates her creditors for want of further munificence. How could Indian officials explain their poor performance relative to Hongkong? Dr Roy has the answers for them. He lists the causes as a large and heavily subsidized public sector, labyrinthine control over private enterprise, forcibly depressed agricultural prices, massive import substitution, government monopoly of foreign exchange transactions, artificially overvalued currency and the extensive politicization of the labour market, not to mention the corruption which is an inevitable side effect of an economy which depends on the arbitrament of bureaucrats. The first Indian government under Nehru took its cue from Nehru’s admiration of the Soviet economy, which led him to believe that the only policy for India was socialism in which there would be “no private property except in a restricted sense and the replacement of the private profit system by a higher ideal of cooperative service.” Consequently, the Indian government has now either a full monopoly or is one of a few oligipolists in banking, insurance, railways, airlines, cement, steel, chemicals, fertilizers, ship-building, breweries, telephones and wrist-watches. No businessman can expand his operation while there is any surplus capacity anywhere in that sector. He needs government approval to modernize, alter his price-structure, or change his labour shift. It is not surprising that a recent study of those developing countries which account for most manufactured exports from the Third World shows that India’s share fell from 65 percent in 1953 to 10 per cent in 1973; nor, with the numerous restrictions on inter-state movement of grains, that India has over the years suffered more from an inability to cope with famine than during the Raj when famine drill was centrally organized and skillfully executed without restriction. Nehru’s attraction for the Soviet model has been inherited by his daughter, Mrs. Gandhi. Her policies have clearly positioned India more towards the Soviet Union than the West. The consequences of this, as Dr Roy states, is that a bias can be seen in “the antipathy and pessimism towards market institutions found among the urban public, and sympathy and optimism to be found for collectivist or statist ones.” All that India has to show for it is the delivery of thousands of tanks in exchange for bartered goods, and the erection of steel mills and other heavy industry which help to perpetuate the unfortunate obsession with industrial performance at the expense of agricultural growth and the relief of rural poverty.”…..

I felt this may have been intended to be laudatory but it was also inaccurate and had to be corrected. I replied dated June 4 which The Times published in their edition of June 16 1984:

I was 29 when Pricing, Planning and Politics was published, I am 54 now. I do not agree with everything I said in it and find the tone a little puffed up as young men tend to be; it was also five years before my main “theoretical” work Philosophy of Economics would be published. My experience of life in the years since has also made me far less sanguine both about human nature and about America than I was then. But I am glad to find I am not embarrassed by what I said then, indeed I am pleased I said what I did in favour of classical liberalism and against statism and totalitarianism well before it became popular to do so after the Berlin Wall fell. (In India as elsewhere, former communist apparatchiks and fellow-travellers became pseudo-liberals overnight.)

The editorial itself may have been due to a conversation between Peter Bauer and William Rees-Mogg, so I later heard. The work sold 700 copies in its first month, a record for the publisher. The wife of one prominent Indian bureaucrat told me in Delhi in December 1988 it had affected her husband’s thinking drastically. A senior public finance economist told me he had been deputed at the Finance Ministry when the editorial appeared, and the Indian High Commission in London had urgently sent a copy of the editorial to the Ministry where it caused a stir. An IMF official told me years later that he saw the editorial on board a flight to India from the USA on the same day, and stopped in London to make a trip to the LSE’s bookshop to purchase a copy. Professor Jagdish Bhagwati of Columbia University had been a critic of aspects of Indian policy; he received a copy of the monograph in draft just before it was published and was kind enough to write I had “done an excellent job of setting out the problems afflicting our economic policies, unfortunately government-made problems!” My great professor at Cambridge, Frank Hahn, would be kind enough to say that he thought my “critique of Development Economics was powerful not only on methodological but also on economic theory grounds” — something that has been a source of delight to me.

Siddhartha Shankar Ray told me when we first met that he had been in London when the editorial appeared and had seen it there; it affected his decision to introduce me to Rajiv Gandhi as warmly as he came to do a half dozen years later.

In the Autumn of 1984, I went, thanks to Edwin Feulner Jr of the Heritage Foundation, to attend the Mont Pelerin Society Meetings being held at Cambridge (on “parole” from the US immigration authorities as my “green card” was being processed at the time). There I met for the first time Professor and Mrs Milton Friedman.

Milton Friedman’s November 1955 memorandum to the Government of India is referred to in my monograph as “unpublished” in note 1; when I met Milton and Rose, I gave them a copy of my monograph; and requested Milton for his unpublished document; when he returned to Stanford he sent to me in Blacksburg his original 1955-56 documents on Indian planning. I published the 1955 document for the first time in May 1989 during the University of Hawaii perestroika-for-India project I was then leading, it appeared later in the 1992 volume Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s, edited by myself and WE James. (The results of the Hawaii project reached Rajiv Gandhi through my hand in September 1990, as told elsewhere here in “Rajiv Gandhi and the Origins of India’s 1991 Economic Reform”.) The 1956 document was published in November 2006 on the front page of The Statesman, the same day my obituary of Milton appeared in the inside pages.

Meanwhile, my main work within economic theory, the “Principia Economica” manuscript, was being read by the University of Chicago Press’s five or six anonymous referees. One of them pointed out my argument had been anticipated years earlier in the work of MIT’s Sidney Stuart Alexander. I had no idea of this and was surprised; of course I knew Professor Alexander’s work in balance of payments theory but not in this field. I went to visit Professor Alexander in Boston, where this photo came to be taken perhaps in late 1984:

Professor Alexander was extremely gracious, and immediately declared with great generosity that it was clear to him my arguments in “Principia Economica” had been developed entirely independently of his work. He had come at the problem from an American philosophical tradition of Dewey, I had done so from a British tradition of Wittgenstein. (CS Peirce was probably the bridge between the two.) He and I had arrived at some similar conclusions but we had done so completely independently.

Also, I was much honoured by this letter of May 1 1984 sent to Blacksburg by Professor Sir John Hicks (1904-1989), among the greatest of 20th Century economists at the time, where he acknowledged his departure in later life from the position he had taken in 1934 and 1939 on the foundations of demand theory.

He later sent me a copy of his Wealth and Welfare: Collected Essays on Economic Theory, Vol. I, MIT Press 1981, as a gift. The context of our correspondence had to do with my criticism of the young Hicks and support for the ghost of Alfred Marshall in an article “Considerations on Utility, Benevolence and Taxation” I was publishing in the journal History of Political Economy published then at Duke University. In Philosophy of Economics, I would come to say about Hicks’s letter to me “It may be a sign of the times that economists, great and small, rarely if ever disclaim their past opinions; it is therefore an especially splendid example to have a great economist like Hicks doing so in this matter.” It was reminiscent of Gottlob Frege’s response to Russell’s paradox; Philosophy of Economics described Frege’s “Letter to Russell”, 1902 (Heijenoort, From Frege to Gödel, pp. 126-128) as “a document which must remain one of the most noble in all of modern scholarship; a fact recorded in Russell’s letter to Heijenoort.”

In Blacksburg, by the Summer and Fall of 1984 I was under attack following the arrival of what I considered “a gang of inert game theorists” — my theoretical manuscript had blown a permanent hole through what passes by the name of “social choice theory”, and they did not like it. Nor did they like the fact that I seemed to them to be a “conservative”/classical liberal Indian and my applied work on India’s economy seemed to their academic agenda an irrelevance. This is myself at the height of that attack in January 1985:

Professor Schultz at the University of Chicago came to my rescue and at his recommendation I was appointed Visiting Associate Professor in the Economics Department at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

I declined, without thanks, the offer of another year at Virginia Tech.

On my last day in Blacksburg, a graduate student whom I had helped when she had been assaulted by a senior professor, cooked a meal before I started the drive West across the country. This is a photo from that meal:

In Provo, I gratefully found refuge at the excellent Economics Department led at the time by Professor Larry Wimmer.

It was at Provo that I first had a personal computer on my desk (an IBM as may be seen) and what a delight that was (no matter the noises that it made). I recall being struck by the fact a colleague possessed the incredible luxury of a portable personal computer (no one else did) which he could take home with him. It looked like an enormous briefcase but was apparently the technology-leader at the time. (Laptops seem not to have been invented as of 1985).

In October 1985, Professor Frank Hahn very kindly wrote to Larry Wimmer revising his 1980 opinion of my work now that the PhD was done, the India-work had led to The Times editorial and the theoretical work was proceeding well.

I had applied for a permanent position at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, and had been interviewed positively at the American Economic Association meetings (in New York) in December 1985 by the department chairman Professor Fred C. Hung. At Provo, Dr James Moncur of the Manoa Department was visiting. Jim became a friend and recommended me to his colleagues in Manoa.

Professor Hung appointed me to that department as a “senior” Assistant Professor on tenure-track beginning September 1986. I had bargained for a rank of “Associate Professor” but was told the advertisement did not allow it; instead I was assured of being an early candidate for promotion and tenure subject to my book “Principia Economica” being accepted for publication. (The contract with the University of Chicago Press had become frayed.)

Hawaii was simply a superb place (though expensive).

Professor James Buchanan won the Economics “Nobel” in 1986 and I was asked by the Manoa Department to help raise its profile by inviting him to deliver a set of lectures, which he did excellently well in March 1988 to the University as well as the Honolulu community at large. Here he is at my 850 sq ft small condominium at Punahou Towers, 1621 Dole Street:

In August 1988, my manuscript “Principia Economica” was finally accepted for publication by Routledge of London and New York under the title Philosophy of Economics: On the Scope of Reason In Economic Inquiry. The contract with University of Chicago Press had fallen through and the manuscript was being read by Yale University Press and a few others but Routledge came through with the first concrete offer. I was delighted and these photos were taken in the Economics Department at Manoa by a colleague in September 1988 as the publisher needed them.

Milton and Rose Friedman came to Honolulu on a private holiday perhaps in January 1989; they had years earlier spent a sabbatical year at the Department.

Here is a luncheon that was arranged in their honour. They had in the Fall of 1988 been on their famous visit to China, and as I recall that was the main subject of discussion on the occasion.

Milton phoned me in my Manoa office and invited me to meet him and Rose at their hotel for a chat; we had met first at the 1984 Mont Pelerin meetings and he wished to know me better. I was honoured and turned up dutifully and we talked for perhaps an hour. I recall making a strong recommendation that he write his memoirs, especially so that the rumours and innuendo surrounding eg the Chile episode could be cleared up; I also said a “Collected Works” would be a great idea; when Milton and Rose published their memoirs Two Lucky People (Chicago 1998) I wondered if my first suggestion had come to be taken; as to the second, he wrote to me years later saying he felt no Collected Works were necessary.

From 1986 onwards, I had been requested by the University of Hawaii to lead a project with William E James on the political economy of “South Asia” .I had said there was no such place, that “South Asia” was a US State Department abstraction but there were India and Pakistan and Sri Lanka and Bangladesh and Afghanistan etc. Sister projects on India and Pakistan had been sponsored by the University, and in 1989 important conferences had been planned by myself and James in May for India and in June for Pakistan.

I was determined to publish for the first time Milton’s 1955 memorandum on India which the Government of India had suppressed or ignored at the time. At the hotel-meeting, I told Milton that and requested him to come to the India-conference in May; Milton and Rose said they would think about it, and later confirmed he would come for the first two days.

This is a photo of the initial luncheon at the home of the University President on May 21 1989. Milton and India’s Ambassador to the USA at the time were both garlanded with Hawaiian leis. The first photo was one of a joke from Milton as I recall which had everyone laughing.

There was no equivalent photo of the distinguished scholars who gathered for the Pakistan conference a month later.

The reason was that from February 1989 onwards I had become the victim of a most vicious racist defamation, engineered within the Economics Department at Manoa by a senior professor as a way to derail me before my expected Promotion and Tenure application in the Fall. All my extra time went to battling that though somehow I managed to teach some monetary economics well enough in 1989-1990 for a Japanese student to insist on being photographed with me and the book we had studied.

I was being seen by two or three temporarily powerful characters on the Manoa campus as an Uppity Indian who must be brought down. This time I decided to fight back — and what a saga came to unfold! It took me into the United States District Court for the District of Hawaii and then the Ninth Circuit and upto the United States Supreme Court, not once but twice.

Milton Friedman and Theodore Schultz stood valiantly among my witnesses — first writing to the University’s authorities and later deposing in federal court.

Unfortunately, government lawyers, far from wanting to uphold and respect the laws of the United States, chose to deliberately violate them — compromising a judge, suborning demonstrable perjury and then brazenly purchasing my hired attorney (and getting caught doing it). Since September 2007, the State of Hawaii’s attorneys have been invited by me to return to the federal court and apologise for their unlawful behaviour as they are required by law to do.

They had not expected me to survive their illegalities but I did: I kept going.

Philosophy of Economics was published in London and New York in September 1989

The hardback quickly sold out on its own steam and the book went into paperback in 1991, and I was delighted to learn from a friend that it had been prescribed for a course at Yale Law School and was strewn along an alley in the bookshop:

The sister-volumes on India and Pakistan emerging from the University of Hawaii project led by myself and James were published in 1992 and 1993 in India, Pakistan, Britain and the United States.

As described elsewhere, the manuscript of the India-volume contributed to the origins of India’s 1991 economic reform during my encounter with Rajiv Gandhi in his last months; the Pakistan-volume came to contribute to the origins of the Pakistan-India peace process. The Indian publisher who had promised paperback volumes of both books reneged under leftwing pressure in Delhi; he has since passed away and James and I still await the University of Hawaii’s permission to publish both volumes freely on the Internet as copyright rests with the University President.

In 2004 from Britain, I wrote to the 9/11 Commission stating that it was possible that had the vicious illegalities against me not occurred at Manoa starting in 1989, we may have gone on after India and Pakistan to study Afghanistan, and come up with a pre-emptive academic analysis a decade before September 11 2001.

To be continued in Part Two.

Milton Friedman’s defence of my work

September 15, 2008 — drsubrotoroyTwenty years have passed since the acceptance of my book Philosophy of Economics for publication — which coincided with the attack on me arising out of the very success of the India-perestroika and Pakistan-perestroika projects I had been leading (an attack from within the University that had sponsored the projects since 1986). I was graced with the support of two of the 20th Century’s great economists, TW Schultz (1902-1998) and Milton Friedman (1912-2006). Professor Schultz’s defence of my work has been published already. Here is that of Professor Friedman. Both Professor Friedman and Professor Schultz were later expert witnesses on my behalf in a federal trial (a trial that unfortunately came to be marred by demonstrable bribery and perjury, yet to be rectified).

Addendum 23 Dec 2016: the jury trial demanded 14 Feb 1990 has never happened; a bench trial with an admittedly compromised judge happened in 1992, marred by demonstrated bribery and perjury https://independentindian.com/thoughts-words-deeds-my-work-1973-2010/my-american-years-1980-96-battling-for-the-freedom-of-my-books/become-a-us-supreme-court-justice-explorations-in-the-rule-of-law-in-america/

An Open Letter to Professor Amartya Sen about Singur etc (2007)

July 31, 2007 — drsubrotoroyA letter to Prof. Sen (2007)

First published in The Statesman 31 July 2007, Editorial Page Special Article

Professor Amartya Sen, Harvard University

Dear Professor Sen,

Everyone will be delighted that someone of your worldwide stature has joined the debate on Singur and Nandigram; The Telegraph deserves congratulations for having made it possible on July 23.

I was sorry to find though that you may have missed the wood for the trees and also some of the trees themselves. Perhaps you have relied on Government statements for the facts. But the Government party in West Bengal represents official Indian communism and has been in power for 30 years at a stretch. It may be unwise to take at face-value what they say about their own deeds on this very grave issue! Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely, and there are many candid communists who privately recognise this dismal truth about themselves. To say this is not to be praising those whom you call the “Opposition” ~ after all, Bengal’s politics has seen emasculation of the Congress as an opposition because the Congress and communists are allies in Delhi. It is the Government party that must reform itself from within sua sponte for the good of everyone in the State.

The comparisons and mentions of history you have made seem to me surprising. Bengal’s economy now or in the past has little or nothing similar to the economy of Northern England or the whole of England or Britain itself, and certainly Indian agriculture has little to do with agriculture in the new lands of Australia or North America. British economic history was marked by rapid technological innovations in manufacturing and rapid development of social and political institutions in context of being a major naval, maritime and mercantile power for centuries. Britain’s geography and history hardly ever permitted it to be an agricultural country of any importance whereas Bengal, to the contrary, has been among the most agriculturally fertile and hence densely populated regions of the world for millennia.

Om Prakash’s brilliant pioneering book The Dutch East India Company and the Economy of Bengal 1630-1720 (Princeton 1985) records all this clearly. He reports the French traveller François Bernier saying in the 1660s “Bengal abounds with every necessary of life”, and a century before him the Italian traveller Verthema saying Bengal “abounds more in grain, flesh of every kind, in great quantity of sugar, also of ginger, and of great abundance of cotton, than any country in the world”. Om Prakash says “The premier industry in the region was the textile industry comprising manufacture from cotton, silk and mixed yarns”. Bengal’s major exports were foodstuffs, textiles, raw silk, opium, sugar and saltpetre; imports notably included metals (as Montesquieu had said would always be the case).

Bengal did, as you say, have industries at the time the Europeans came but you have failed to mention these were mostly “agro-based” and, if anything, a clear indicator of our agricultural fecundity and comparative advantage. If “deindustrialization” occurred in 19th Century India, that had nothing to do with the “deindustrialization” in West Bengal from the 1960s onwards due to the influence of official communism.

You remind us Fa Hiaen left from Tamralipta which is modern day Tamluk, though he went not to China but to Ceylon. You suggest that because he did so Tamluk effectively “was greater Calcutta”. I cannot see how this can be said of the 5th Century AD when no notion of Calcutta existed. Besides, modern Tamluk at 22º18’N, 87º56’E is more than 50 miles inland from the ancient port due to land-making that has occurred at the mouth of the Hooghly. I am afraid the relevance of the mention of Fa Hiaen to today’s Singur and Nandigram has thus escaped me.

You say “In countries like Australia, the US or Canada where agriculture has prospered, only a very tiny population is involved in agriculture. Most people move out to industry. Industry has to be convenient, has to be absorbing”. Last January, a national daily published a similar view: “For India to become a developed country, the area under agriculture has to shrink, urban and industrial land development has to take place, and about 100 million workers have to move out from agriculture into industry and services. This is the only way forward for bringing prosperity to the rural population”.

Rice is indeed grown in Arkansas or Texas as it is in Bengal but there is a world of difference between the technological and geographical situation here and that in the vast, sparsely populated New World areas with mechanized farming! Like shoe-making or a hundred other crafts, agriculture can be capital-intensive or labour-intensive ~ ours is relatively labour-intensive, theirs is relatively capital-intensive. Our economy is relatively labour-abundant and capital-scarce; their economies are relatively labour-scarce and capital-abundant (and also land-abundant). Indeed, if anything, the apt comparison is with China, and you doubtless know of the horror stories and civil war conditions erupting across China in recent years as the Communist Party and their businessman friends forcibly take over the land of peasants and agricultural workers, e.g. in Dongzhou.

All plans of long-distance social engineering to “move out” 40 per cent of India’s population (at 4 persons per “worker”) from the rural hinterlands must also face FA Hayek’s fundamental question in The Road to Serfdom: “Who plans whom, who directs whom, who assigns to other people their station in life, and who is to have his due allotted by others?”

Your late Harvard colleague, Robert Nozick, opened his brilliant 1974 book Anarchy, State and Utopia saying: “Individuals have rights, and there are things no person or group may do to them (without violating their rights)”. You have rightly deplored the violence seen at Singur and Nandigram. But you will agree it is a gross error to equate violence perpetrated by the Government which is supposed to be protecting all people regardless of political affiliation, and the self-defence of poor unorganised peasants seeking to protect their meagre lands and livelihoods from state-sponsored pogroms. Kitchen utensils, pitchforks or rural implements and flintlock guns can hardly match the organised firepower controlled by a modern Government.

Fortunately, India is not China and the press, media and civil institutions are not totally in the hands of the ruling party alone. In China, no amount of hue and cry among the peasants could save them from the power of organised big business and the Communist Party. In India, a handful of brave women have managed to single-handedly organise mass movements of protest which the press and media have then broadcast that has shocked the whole nation to its senses.

You rightly say the land pricing process has been faulty. Irrelevant historical prices have been averaged when the sum of discounted expected future values in an inflationary economy should have been used. Matters are even worse. “The fear of famine can itself cause famine. The people of Bengal are afraid of a famine. It was repeatedly charged that the famine (of 1943) was man-made.” That is what T. W. Schultz said in 1946 in the India Famine Emergency Committee led by Pearl Buck, concerned that the 1943 Bengal famine should not be repeated following dislocations after World War II. Of course since that time our agriculture has undergone a Green Revolution, at least in wheat if not in rice, and a White Revolution in milk and many other agricultural products. But catastrophic collapses in agricultural incentives may still occur as functioning farmland comes to be taken by government and industry from India’s peasantry using force, fraud or even means nominally sanctioned by law. If new famines come to be provoked because farmers’ incentives collapse, let future historians know where responsibility lay.

West Bengal’s real economic problems have to do with its dismal macroeconomic and fiscal position which is what Government economists should be addressing candidly. As for land, the Government’s first task remains improving grossly inadequate systems of land-description and definition, as well as the implementation and recording of property rights.

With my most respectful personal regards, I remain

Yours ever

Suby

Land, Liberty & Value

December 31, 2006 — drsubrotoroyLAND, LIBERTY & VALUE

Government must act in good faith treating all citizens equally ~ not favouring organised business lobbies and organised labour over an unorganised peasantry

By SUBROTO ROY

First published in The Sunday Statesman Editorial Page Special Article, December 31 2006