India-Pakistan Diplomacy During the 1965 War: the MK Roy Files

by Subroto Roy

7 November 2015

First published at Twitter Sep-Oct 2015 under #1965War

(NB this is a draft copy still in process of being published fully, coinciding with MK Roy’s Birth Centenary on 7 November 2015; the quality of the scanned documents will also improve in due course when the Twitter copies are no longer used)

1. Introduction

2. Emergency declared in Pakistan

3. British and American responses

Appendix: Airconditioners, AID, Atrocities & Archer Blood

4. Pakistan air attacks in Eastern India

5. Fear of Disease, Violence against 458 Indian hostages

6. Note Verbale 15 September 1965

7. Babies born

8. Foreign evacuations from Dhaka planned

9. Pakistan demands India’s flag be lowered: MK Roy refuses

10. Mrs AK Ray’s planned evacuation

11. Ceasefire: Restoring communications

12. Note Verbale 1 October 1965

13. Myanmar’s help: My sister & I leave via Rangoon

14. Indian treatment of Pakistan diplomats “by the book”

15. November 1965 Indian protests to Pakistan Govt

16. Further analysis & conclusions

1. Introduction

“Amra Lahore attack koreychhi”, “We’ve attacked Lahore”, my father said with some tense pride one day in Dhaka in early September 1965, to me his ten year old son. He was referring to Lal Bahadur Shastri’s counter-offensive towards Lahore and Sialkot on 6 and 7 September, responding to the Pakistani campaigns in Kashmir that had commenced 5 August and 1 September (pompously titled “Gibraltar” and “Grand Slam”).

Throughout that short fierce war in 1965, MK Roy was India’s Acting Deputy High Commissioner in the capital of Pakistan’s “Eastern wing”. Ayub Khan’s attacks on Indian territory originated in West Pakistan, and it became J&K, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat where the military battles were fought; the contest in East Pakistan turned out to be one of fierce diplomacy following mutual air attacks for a few days. Described herein is the experience of the large community of Indian diplomatic officials in the Deputy High Commission (effectively a Consulate General) in East Pakistan led for the duration of the war by MK Roy. Lateral reference is made too to the similar experience of Indian diplomatic officials in the High Commission (or Embassy) in West Pakistan at the time led by Kewal Singh.

Kewal Singh arrived in Karachi, Pakistan’s old capital, on 5 August 1965 succeeding G Parthasarathi who went as India’s envoy to the UN. Kewal Singh was asked by the Pakistan side to present his credentials the following day in the new capital Islamabad. The date set for credentials to be presented had been five days after arrival; Ayub Khan to whom Kewal Singh would present his credentials, was the author along with his Foreign Minister ZA Bhutto of the “Gibraltar” and “Grand Slam” attacks that were starting right then; the Pakistan side craftily brought the presentation date forward to 6 August, knowing it would become more awkward after news of “Gibraltar” had spread. Kewal Singh had been born and raised in West Punjab and spent his first 30 years there, he felt emotionally attached to the place and people, he admits he waxed eloquently to Ayub about how Indians and Pakistanis were brothers, how if his Government asked him to do anything “intended to hurt Pakistan’s national interest”, he would resign his ambassadorship instead. Ayub responded with equal platitudes about how both countries were wasting resources on the military better spent on economic development — except Kewal Singh’s expressions and proposals of fraternity, ignorant of the Pakistani aggression that had started right then, were meant genuinely, Ayub’s were deceptive.

2. Emergency declared in Pakistan

My father became the ranking Indian diplomatic officer in Dhaka during the war because Deputy High Commissioner AK Ray left for Kolkata on 3 September 1965. Ray left on the same Indian Airlines plane as my mother, who had been called back to India due to a family illness. Ray did not return to his post in Dhaka until 16 October 1965. Next in line after MK Roy in Dhaka was PN Ojha who had replaced Sailen C Ghosh (father of the author Amitav Ghosh) in April 1965; both Ghosh and Ojha were Intelligence Bureau officers deputed to the Foreign Service (Ghosh even finding mention in a Nehru speech to Parliament a few years earlier). Other diplomatic officers in West Pakistan included Deputy High Commissioner Prakash Narain Kaul and Kayatyani Shankar Bajpai in Karachi, and Girdhari Lal Puri in Lahore. Puri was a former NWFP legislator and journalist who had been born in Lahore; in 1965 he was Counselor in Karachi, Liaison Officer in Islamabad, and effectively Deputy High Commissioner in Lahore, a vital resource for the isolated embassy in Karachi; he along with Balraj Kapur and a few others may also have given advance warning of the 1947 Pakistani attack on Kashmir.

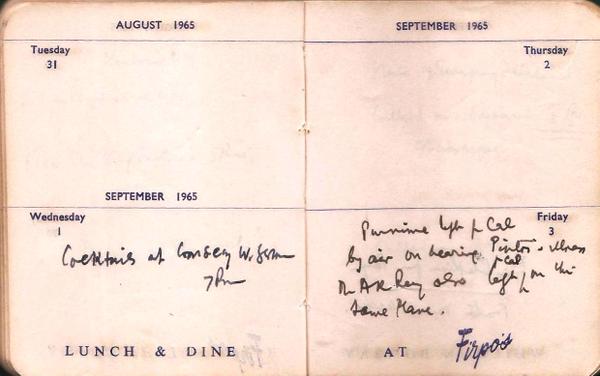

My father’s diary records “Cocktails at Consul General, West Germany” on 1 September — the day Ayub’s “Grand Slam” against India commenced.

The Pakistan Government, having provoked war in August with “Gibraltar” and started it full-scale formally on 1 September with “Grand Slam”, was itself caught by surprise on 6 September by PM Shastri’s riposte against Lahore and Sialkot, and declared a State of Emergency. In Dhaka, my father at 5 pm phoned the East Pakistan Government’s Home Secretary AQ Ansari requesting police protection for Indian diplomatic officers and staff, at 8 pm Ansari asked him to meet him at once. Later the same night of 6 September, MK Roy wrote to Ansari demanding normal police protection for Indian officials:

In Karachi, Kewal Singh had had a gathering premonition of doom since coming to know of “Gibraltar”, though he had been kept in the dark by the Foreign Ministry in Delhi except for being asked to strenuously object to “Gibraltar” and warn the Pakistan Government of inevitable consequences if they failed to desist. He had been prevented from meeting Ayub to convey Shastri’s warning, but had been allowed to meet Foreign Minister ZA Bhutto, who had in all likelihood instigated Ayub to authorise “Gibraltar”. Bhutto baldly lied to Kewal Singh, denying there was anything going on other than a spontaneous Kashmiri uprising against India. On 27 August, Kewal Singh sent an officer (Attache Bhaumik) to Delhi with a trunk full of secret and confidential files of the embassy for safe-keeping. (Bhaumik went too to fetch his mother as his wife was heavily pregnant in Karachi; he could not return). On 6 September at noon Kewal Singh and his officers gathered in his office to hear Ayub Khan declare to the people of Pakistan on the radio “We are at war” — though war never came to be formally declared between the two countries. Ayub and Bhutto, who were respectively Sandhurst and communist influenced Muslim modernists, and later Maulana Maududi, whose orthodoxy had set him against the Pakistan Movement, would all declare the 1965 war was a *jihad* against India (Ayub: “India has dared to go to war with a people whose hearts are filled with the message of Kalama of Quran…”). But this jihad theory was rendered nonsense by India’s highest gallantry award in the war going first to a Muslim NCO of the Grenadiers, Abdul Hamid, posthumously, who would on 10 September single-handedly destroy several Pakistani tanks (the only other recipient of the award was the tank commander Col Ardeshir Tarapore, whose daughter recalled him famously saluting his wife and the gathered women and families as his train pulled out of the station going to war).

Between the 6th and evening of the 8th, Kewal Singh got his officers to quietly purchase incinerators and destroy by burning all remaining secret and confidential files of the embassy — including their cypher code books. On the night of the 8th, the embassy came to be attacked and ransacked in the middle of the night by the West Pakistan police, looking allegedly for radio transmitters. The next night at 1.30 am Kewal Singh was required to attend at the office of the Pakistan Foreign Secretary Aziz Ahmed.

Oddly enough, Aziz Ahmed called in Kewal Singh three full days after Ansari in Dhaka had called in MKRoy; perhaps West Pakistan got the idea after hearing East Pakistan had done so. Whereas MKRoy left Ansari in equanimity enough on 6 September and had written Ansari a letter immediately demanding police protection, Kewal Singh on the night of the 9th/10th was subjected to the most awful unending anti-Hindu anti-Indian harangue by Aziz Ahmed. Aziz Ahmed was said to have been an author with ZA Bhutto of “Gibraltar” and even to have received information from the Turkish Embassy in Delhi on 4 September of a planned Indian counter-offensive. Yet he subjected Kewal Singh to an ugly unprecedented tongue-lashing, which so embarrassed the Pakistani protocol officer who was witness to it that he bravely apologized to Kewal Singh on his way out; that Pakistani protocol officer was Humayun Rashid Choudhury who would come to lead in 1971/2 the defection of East Pakistani diplomats to the new Bangladesh, and help obtain recognition of Bangladesh by many countries.

3. British and American responses

On 7 September, trying to get through to Kewal Singh and the embassy in Karachi, MK Roy called on his UK and US counterparts. MK Roy’s diary records:

He found British diplomats “cold unhelpful”, the Americans “responsive”.

The UK Deputy High Commissioner, KR Crook (1920-2012), had come to Dhaka from Peshawar; decades later he would end his career as Ambassador to Afghanistan; he may have been part of the notoriously powerful pro-Pakistan lobby in the UK Foreign & Commonwealth Office, traditionally hostile to India over J&K. I have said it should not at all surprise if further research found British diplomats in Dhaka like KR Crook had been consulted by the West Pakistani officials running East Pakistan’s Government at the time as to how to proceed with war-time internment of Indian diplomats and their families. Prof Arun Banerji of Jadavpur University noted in The Statesman of 4 October 2015 that British journalists themselves found evidence of official British “ignorance”, “anti-Indian feelings”, “malice” and “spite” against India and “partiality for Pakistan” in the 1965 War, including on part of the BBC.

The “responsive” US Consul General John W Bowling was an experienced scholarly professional whose ambit had earlier included Greece, Turkey, Iraq and Iran besides the subcontinent. Years later Bowling would be credited with having been the “most prescient” US diplomat in predicting “rightist opposition” to the Shah of Iran. In his Dhaka discussion with my father on 7 September 1965, Bowling challenged MK Roy over Indian air attacks in East Pakistan, mentioned a Communist Chinese threat being perceived by the Americans in East Pakistan, and hinted at an American evacuation being planned from there.

Appendix: Airconditioners, AID, Atrocities & Archer Blood

I as a ten year old was invited once to visit alone one afternoon a senior American diplomat, his wife and adult son at home as they lived very near us in Dhanmondi; it may have been Bowling himself or more likely one of his colleagues — possibly Paul Baxter Lanius Jr who headed the Economic Section and whose daughters may have been with me at “Mrs Coventry’s Farm View School”; perhaps they were curious to talk to an Indian boy or perhaps my mother had officiously arranged it because she assumed the two sons could be friends! I was tongue-tied during the visit, my hosts were very friendly and expansive, and I recall the Coca Cola, snacks, and especially the air-conditioning so cold and delicious. It is my first memory of the hierarchy and superiority established in the tropics by cold air-conditioning over the ceiling fans we were used to. “But why are you giving Pakistan Sabre jets to fight India with?” I had either blurted out to my hosts, or felt myself wanting to blurt out, before I fled home quickly from my brief diplomatic engagement.

My boyhood memory of air-conditioned Americans in Dhaka was somewhat confirmed decades later by that hero of Bangladesh, Archer Blood himself in an interview!

The American diplomat Archer Kent Blood (1923-2004) had two postings in Dhaka, the first as Political Officer between 1962-1964, the second as Consul General 1970-1971. He said in the interview the USA in Pakistan “had a large Agency for International Development mission. The AID mission director in Karachi, which was still then the embassy, had much more access to the leadership of Pakistan than did our ambassador. In East Pakistan, the director of the AID mission had more access to the governor than did the consul general. There was considerable friction between the two. AID was, in those days, a big dominant organization which threw its weight around a lot….AID for instance lived so much better than the rest of us lived. They all had airconditioners in every room of their house and air-conditioned automobiles. We didn’t. It was sort of a two-class society in East Pakistan. The Foreign Service and the USIA and CIA were sort of the lower class, and AID was the upper class.” But the AID staff in 1971 did make up for their air-conditioned pampering by authoring the famous Archer Blood telegrams to Washington recording the West Pakistani atrocities in the emerging Bangladesh. Blood said in the interview: “Actually, the dissent message was drafted by 12/13 people on my staff. I did not draft it. They came to me and said we want to send this statement, we are so upset with the US failure to denounce the atrocities. They were all key people in AID, USIA. My own deputy didn’t,but he was a weak officer, I think he decided he was too scared or something. But everybody whose opinion I respected had participated. So I decided to send it and I transmitted it. But I transmitted it along with a strong supportive statement. I said, ‘I had not personally drafted this. It was presented to me. But these are my best officers. I believe in what they are saying. I accord with their sentiments completely,’ and sent it off.”

Blood’s predecessor Bowling saying to my father in 1965 that the US teleprinter in Dhaka was “very old” makes one wonder: did this teleprinter change before the famous Blood telegrams half a dozen years later in 1971 recording West Pakistani atrocities in the emerging Bangladesh?

4. Pakistan air attacks in Eastern India

The Pakistan Air Force in East Pakistan in 1965 had one squadron of American-made F86 Sabres, a dozen or so planes. These, and the even more formidable American F104 Starfighter also given to Pakistan, had air to air missile capabilities. India’s British-made Gnats and Hunters and French-made Mysteres did not, relying on machine-guns for aerial combat (according to the Official History of India’s Ministry of Defence). Yet as it happened Gnats and Hunters brought down Sabres, a Mystere even brought down an F104, and prime American-made Patton tanks perished en masse through clever Indian strategy at Asal Uttar before the war ended.

One Sabre jet went on sentry duty twice every day over Dhaka. At 10 am the traditional British Carter Gents air raid warning siren would sound, the plane would appear and fly in a large circle around Dhaka several times, followed by the All Clear siren; the same would be repeated at 6 pm at dusk.

Even with so few planes in East Pakistan, the PAF apparently attacked with ferocity Indian airfields at Kalaikunda, Barakpur, Bagdogra, Agartala, Guwahati in the initial days of the war. India had apparently responded in the manner John W Bowling informed MK Roy, on the basis of the Pakistan Government having taken foreign observers around to complain about damage India had caused. MK Roy told Bowling not to believe the Pakistani propaganda, and that India, in declared policy announced by All India Radio, had said it would not escalate the war by land in East Pakistan. East Pakistan had only one infantry division and the Pakistan Government in attacking Indian airfields was probably banking on the announced Indian policy that India would not invade East Pakistan.

The single East Pakistan F86 squadron made its fierce attacks in the first few days, lost half a dozen aircraft to antiaircraft fire over India or Indian fighter action, then fell silent. Yet that aggressive single PAF squadron did tie down Indian Air Force resources from being used in the Western sector, something noted too by the Indian strategist Jasjit Singh, and thus may have affected the outcome of the war. In his account of the 1971 Bangladesh war, Lt General AAK Niazi who surrendered Pakistani forces to an Indian and Bangladeshi command at Dhaka Race Course on 16 December 1971, complained that Pakistani military doctrine had been that the defence of East Pakistan was supposed to be in West Pakistan. Pressure of an Indian invasion of East Bengal was to be relieved by Pakistan’s hidden second armoured division attacking in East Punjab; that did not materialise in 1971, Niazi moaned in his memoirs. Indeed to the contrary, Niazi was compelled by orders to surrender, he claimed, in order to save West Pakistan from further Indian attack. In 1965 too, the single PAF squadron of Sabres in East Pakistan pinned down Indian air resources with its initial ferocity, banked on no Indian retaliation on the ground and little in the air, and accordingly may have affected the outcome in the Western sectors.

5. Fear of Disease, Violence Against 458 Indian Hostages

On 8 September 1965, my father in increasingly bitter negotiations with the East Pakistan Government to have the Indian community adequately and safely housed during the war, ended up declaring to Pakistani officials

“we have to live as neighbours for ever”

“such harassment and intimidation would always remain a sore point between us”.

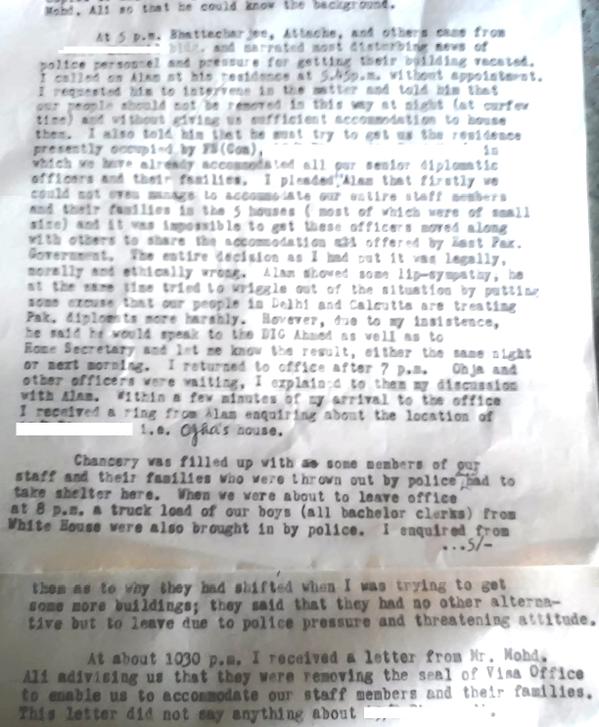

A little diplomatese had continued in the talk, e.g. a suggestion by Home Secretary Ansari at the 6 September meeting that my father use an “en clair telegram”, not encrypted in code or cipher, to be in touch with the Karachi embassy. That did not happen. MK Roy asked to be allowed to be in touch with Karachi even using the Pakistan Government’s office phones to do so. It was not allowed. On 9 September, the Pakistan Government set aside all diplomacy and used their police to forcibly close the Indian Visa Office. By 10 September, the Indian request for police protection in time of war had been transformed into the Indian diplomatic community instead beginning its days as hostages in the war. MK Roy “gatecrashed into the Home Secretary’s office” to state his objections.

By 11 September, more than 450 Indians had become hostages to the war: something “legally, morally wrong” MK Roy declared to the Pakistanis.

By 12 September, second week of the war, some 450 Indians were under arrest by armed police crammed into five houses (and later the Visa Office too) designated by the East Pakistan Government.

On 13 September, my father, older sister Tunu, and I moved to the residence of Mrs AK Ray, along with Mr and Mrs George who lived in the flat below us. My father as Acting Deputy High Commissioner was given the choice by the Pakistan Government of remaining in our flat but all things considered he decided we should move. Some time between the 6th and 12th, he and Tunu (and I too) burnt official files in our pantry and kitchen in case we were run over. We did the burning in the dark, possibly on the night of the 12th as PN Ojha had visited my father at home in the morning.

So my father as Acting Deputy High Commissioner, Mrs AK Ray and her son, and the Georges, besides my older sister and myself were in the Deputy High Commissioner’s residence, while some 450 other Indian officers, staff and families were crammed into five other houses (and later the Visa Office), all effectively hostages under the East Pakistan Government’s armed police.

Mrs Ray’s son Arjun and I were friends: he later recalled to me that our playing with battery torches in the dark blackouts in the evenings was objected to formally by the Pakistani police as possibly signalling Indian bombers in the night sky! I recall a bad stone fight where street-boys outside tossed stones at us over the wall into the compound — the armed police doing nothing — and we tossed some back; we were soon being out-stoned, yet being reckless boys we would not stop until my father heard about it and came to take us indoors.

In Karachi, Kewal Singh, who had been interned separately and was mostly unaware what was happening to his officers and their families, recorded he was very concerned about mob violence, which in fact did take place against the embassy premises. That was in addition to the West Pakistan armed police making a vicious violent search of the whole chancery premises in the middle of the night, in search ostensibly of radio-transmitters which of course did not exist! The Karachi mission was left without any normal transistor radios for the duration of the war; in Dhaka under arrest our radios allowed us to secretly listen to AIR in the dark blacked-out evenings, our sole connection to the outside world during the war. Mrs Ray had taught her son to play bridge, and she and he paired opposite the Georges often in the daytime as I recall.

My older sister Tunu and I wondered about what the future held for us. Tunu had had to help my father burn files in our own flat; Dhaka unlike Karachi had not taken the precaution of buying incinerators ahead of time if any were to be had. Another point of difference between Karachi and Dhaka had to do with embassy ciphers or code-books for use in sending encrypted messages. In Karachi Kewal Singh’s officers had not only burnt confidential documents, they had also destroyed their codes and ciphers. Hence Kewal Singh recorded his Deputy PN Kaul being very angry with Delhi for eventually remembering them after the war had ended and sending their first message in code which they could no longer read! In Dhaka, MK Roy, PN Ojha and others had managed to preserve not only their radio receivers for the news but also their codes and ciphers, and hence could restart encrypted communications once the war was over (though not with Karachi who could not read them!)

My father’s constant fear was of an engineered massacre taking place in one of the other houses, with the Pakistani police supposedly protecting the inhabitants saying they could do nothing. He had seen the Calcutta riots and killing in 1946; in August 1947 as a young Government of India officer of the Supply Department in Karachi, the information he brought back to Shyama Prosad Mukherjee, his Minister (who had been also a family friend, as had been his father Ashutosh of SN Roy) and through him to the Nehru Cabinet, had helped save the masses of Hindu Sindhis from threats of massacre and abduction of women; the Sindhis came to be evacuated safely to India after Nehru decided, when he heard my father’s information from Mukherjee, to immediately send frigates from Bombay to Karachi. MK Roy, then 32, was rewarded by both Nehru and the departing Mountbatten with invitations to meals.

Now, in Dhaka in 1965, the manner in which the hundreds of Indians had been forcibly crowded into five houses under unsanitary conditions and placed under armed arrest concerned my father greatly, as the situation could easily become volatile in unpredictable ways, leading to violence which the Pakistani authorities would plead helplessness about ex post facto. Had Indian fighting extended to Lahore, the risk of a massacre of Indian civilians in Dhaka in retaliation would have increased.

6. Note Verbale 15 September 1965

Kewal Singh in Karachi before he was interned made a visit to his Sri Lankan counterpart seeking help to communicate with Delhi but did not get it. MK Roy had managed visits to his UK and US counterparts. He then decided on 15 September 1965 to send a strongly worded Note Verbale to the Pakistan Government citing their violations of the Vienna Convention. Copies of this Note Verbale were sent with covering letters to the Doyen of the diplomatic corps in Dhaka who was the Japanese Consul General K. Takenaka, and also to John W. Bowling of the USA and KR Crook of the UK. Notifying the Dhaka diplomatic community of how the 458 Indians had become hostages in violation of the Vienna Convention, reduced the risk of an untoward incident arising by the Pakistan Government against us in the heat of the war being fought in the Western sectors.

The Japanese Consul General had gone to Lahore and did not receive it. The British again “took no action”, the American Consul General was again sympathetic and “cooperative”, warning of an epidemic breaking out among “a large number of personnel living under unhygienic conditions” with overflowing sewers and burst septic tanks.

7. Babies born

No deaths or injuries by violence or disease occurred on my father’s watch in those weeks among the 458 Indians interned in Dhaka during the 1965 War. Three births did take place.

The first birth was to Mrs Nar Singh, the wife of a peon, which happened without medical help inside the Visa Office (being used as a residence by more than 100 people) at 4 am on the night of the 16/17th September. (In Karachi, Mrs Bhaumick, wife of Attache Bhaumick who had been sent to Delhi with documents and was supposed to return with his mother, also gave birth — without her husband or mother in law or apparently doctors, only the help of the embassy ladies.)

The second lady in an advanced state of pregnancy was Mrs J S Bhatti, wife of an India-based clerk. The third lady in an advanced pregnancy was Mrs AK Ray herself. Here the Pakistan Government refused to allow Mrs Ray to see her own doctor at Holy Family Hospital; they sent their own chosen doctor from the Government Hospital one morning to her residence — whom the Indian files record, rightly or wrongly, as being rumoured to be “well known as an abortionist” — and insisted that Mrs AK Ray submit to being treated by her. The Indians found this most objectionable and Mrs Ray refused this doctor. A nurse sent along too was also refused by the Indian side as a likely spy. According to the diary, through some slight subterfuge by my father and Mrs Ray sweet-talking the Pakistani police at the gates, Mrs Ray was able to slip away to Holy Family Hospital unscheduled with a police sergeant accompanying her; she came back “very happy” at having seen her own doctor and brought back certificates about her health from the doctor; she had also passed on a message to Mrs Bowling who was being evacuated with other Americans to Manila, and was also able to bring back some baby clothes sent by Mrs Bowling.

8. Foreign evacuations from Dhaka planned

As Bowling had indicated to my father at the 7 September meeting, the Americans (and British) began evacuations of their nationals in East Pakistan from Dhaka airport, certainly by 17 September if not earlier. We have to surmise there was intense diplomatic pressure on the Government of Pakistan after the first few days not to escalate an air war in East Pakistan for fear of Indian retaliation damaging Dhaka airport preventing these evacuations of foreign diplomats and other nationals. Indeed if US nationals were being planned by Bowling to be evacuated when he met my father on 7 September, as they in fact came to be soon enough (perhaps in fear of the Communist Chinese intervention mentioned by Bowling), there would have been much international pressure on both Pakistan and India to call a cease-fire to allow this to happen; the actual ceasefire did occur a week later. As of 17 September, however, no one knew when the war would in fact end. The Americans had started evacuations as had other nationalities, and talk began shortly afterwards to evacuate Mrs Ray and her son with them.

9. Pakistan demands India’s flag be lowered: MK Roy refuses

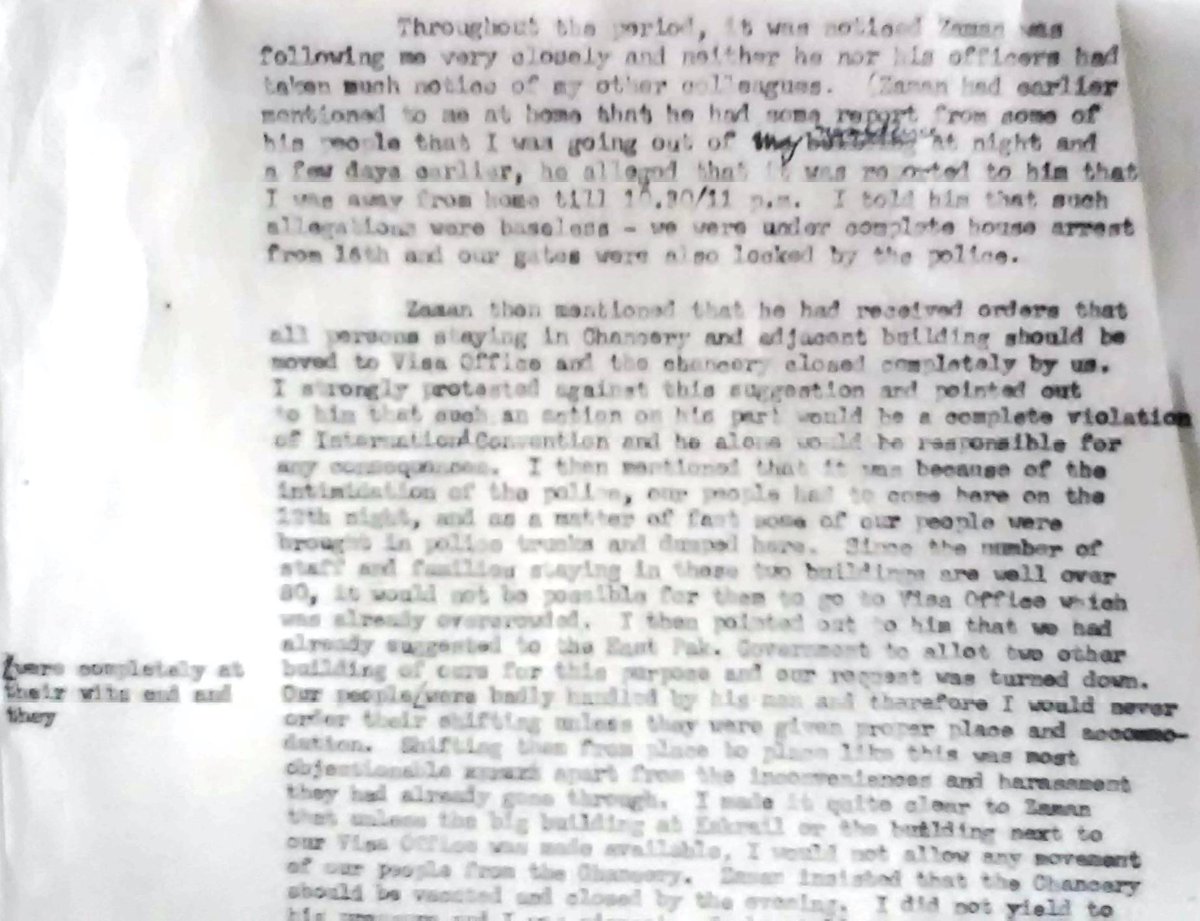

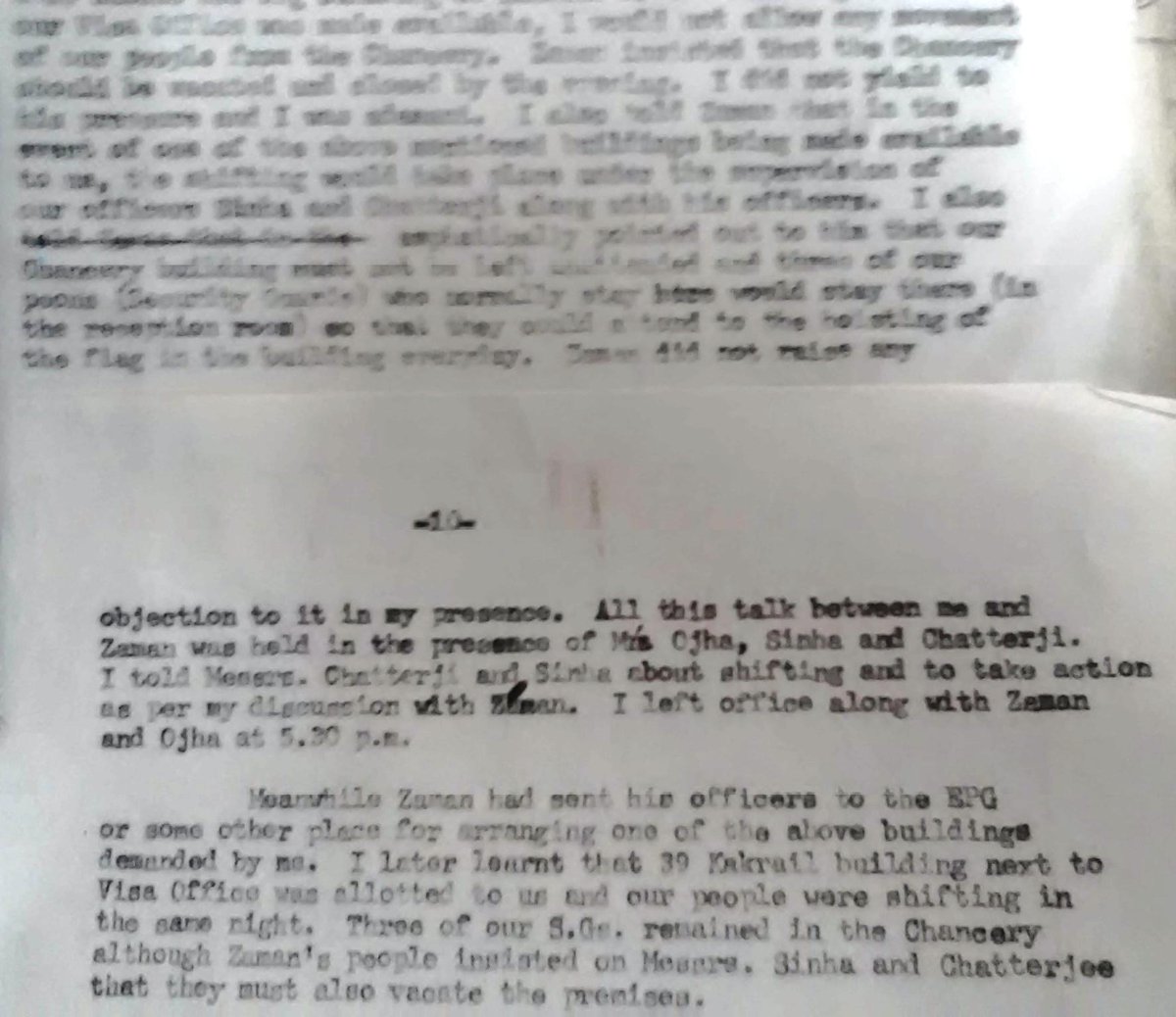

On 18 September, Pakistan Government behaviour towards the Indian diplomatic hostages in Dhaka reached its nadir. The Pakistan Government demanded India’s flag come down from the Chancery premises and residence of MK Roy as Acting Deputy High Commissioner. MK Roy refused.

(from the 4 November 1965 formal protest by the Ministry of External Affairs to the Pakistan envoy)

(from 1 October 1965 Note Verbale to the East Pakistan Government citing the Vienna Convention)

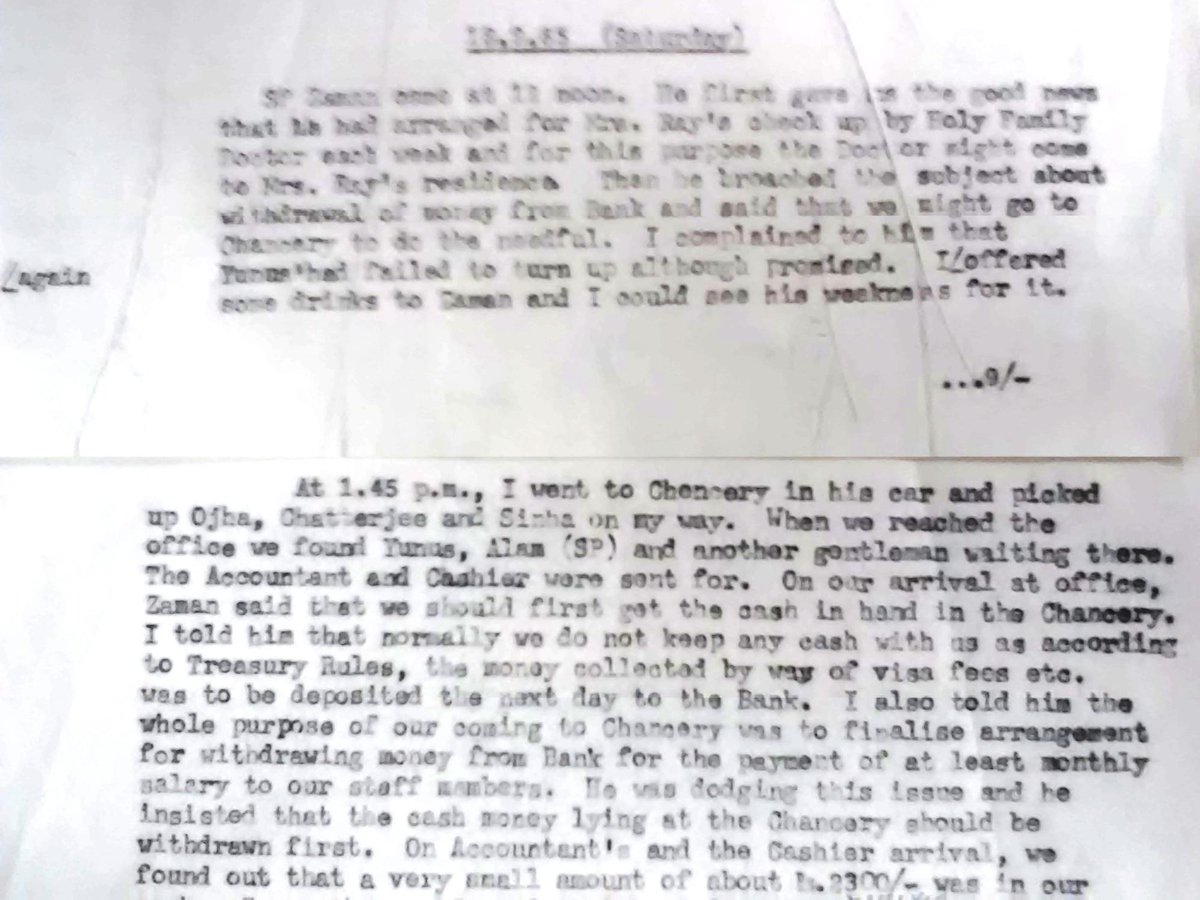

My father has no diary entry for 19 September , only the 18th:

On 19 September the Pakistan Government forcibly closed India’s Dhaka Chancery using the police, and emptied it of personnel. I recall my father in a small group raised India’s flag on the lawn flagpole of where we resided. He had looked at me and smiled slightly in the tension while doing so. Street boys threw stones from outside over the walls and gates of the compound at us in the lawn; somehow Jana Gana Mana was sung. India’s flag kept flying.

10. Mrs AK Ray’s planned evacuation

On 20 September, the Government of Pakistan wrote to my father saying they were willing to see Mrs AK Ray evacuated in view of her condition. The Pakistan Government offering this on their own may have been a result of American intervention again as Mrs AK Ray had managed three days earlier to get a message to Mrs Bowling who was being evacuated to Manila.

MK Roy wrote back immediately.

There is nothing on record for 21 September but tensions in Dhaka were apparently reducing alongside the foreign evacuations taking place. On 22 September, Mrs AK Ray’s evacuation planned on a British evacuee flight the same day became slightly farcical: my father informed Pakistani authorities Mrs AK Ray had been told by her doctor her condition was delicate “and there is every possibility that she may give birth to a child in Singapore on arrival” and hence she and her son needed “comfortable seating accommodation” in the British passenger aircraft to Singapore.

The Pakistan Government wished not to know and pleaded helplessness; my father ended up writing a note to the Captain of the British aircraft asking him to radio forward to Singapore the information about his passenger!

All of this became moot as All India Radio, our lifeline, announced Ceasefire had been declared. The 1965 war between Pakistan and India begun by Ayub Khan in August concluded on the night of 22/23 September. Mrs AK Ray and her son were not evacuated after all; she gave birth in Dhaka at Holy Family Hospital almost four weeks later on 18 October 1965 to her child, the present Mrs Reshmi Ray Dasgupta, wife of the journalist Swapan Dasgupta. Five days earlier, on 13 October, Mrs JS Bhatti had given birth to her child also at Holy Family Hospital.

11. Ceasefire: Restoring communications

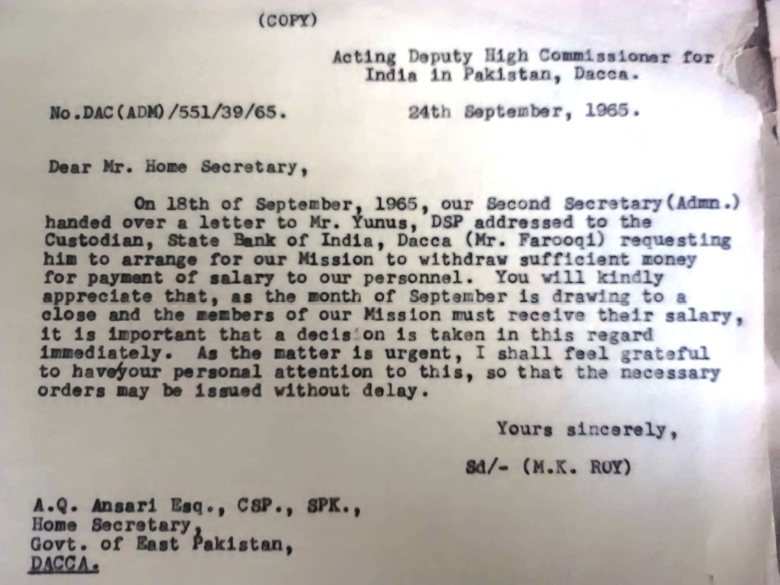

The East Pakistan Government did not appear to respond to the Ceasefire significantly, and on 24 September MK Roy had to write again to AQ Ansari, Home Secretary, demanding that they do so.

The moneys of the Indian diplomatic mission had been seized by the Pakistan Government as “Enemy Property”, and had to be immediately asked to be released: staff had to have salaries to buy provisions with!

On 25 September, 54 hrs after the Ceasefire, the Pakistan Government had still not released its Indian diplomat internees. MK Roy demanded to know again from Ansari what the Pakistanis intended:

He then wrote to Ansari’s superior officer, East Pakistan Government Chief Secretary Ali Asgar, demanding a meeting:

The Indians were still interned as of 26 September. Finally there was movement on 27 September and MK Roy with two of his officers immediately visited all his colleagues in the houses.

On the afternoon of the 27th, Ansari with hypocritical solicitude released his prisoners

On 28 September, work commenced again, and the first task was to establish communications with Karachi.

MK Roy also asked Indian Embassy Rangoon which was closest, to inform AK Ray in Kolkata that Mrs AK Ray was keeping well, and he asked Ray to inform my mother that my sister and I were fine and would return as soon as flights resumed.

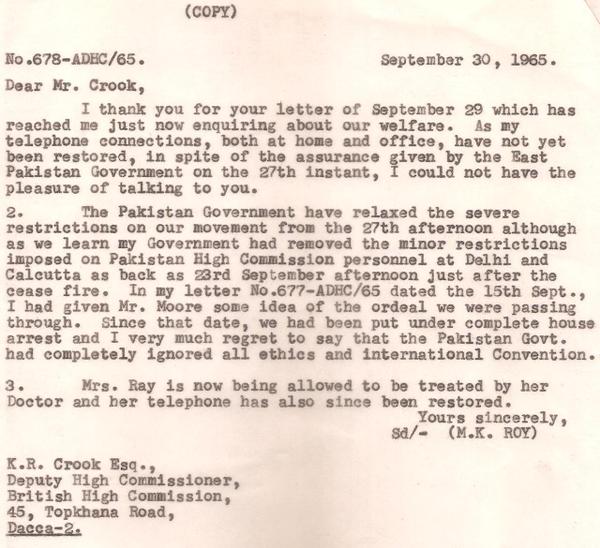

The British diplomat KR Crook now made a solicitous inquiry about the welfare of the Indians in Dhaka, which had to be responded to politely:

The return of AK Ray had to be negotiated:

12. Note Verbale 1 October 1965

On 1 October 1965, MK Roy sent a lengthy Note Verbale to the Pakistan Government documenting the unlawful behaviour experienced during the war by the Indian diplomatic community, specifically the demand by Pakistan that the Indian flag be lowered from the Chancery and the Acting DHC’s residence. The Pakistan Government had forcibly by police action brought the flag down closing the Chancery — but my father, as noted earlier, somehow got the flag flying again on the lawn-pole of where we were residing; I recall as I have said he smiled at me slightly in the tension as that happened. Somehow Jana Gana Mana got sung while the street boys outside pelted stones over the wall of the compound. That must have been 19 September, just a few days before the Ceasefire. The 1 October 1965 Note Verbale recorded India’s protest at the outrage.

Of interest is the East Pakistan Police Superintendent Zaman telling MK Roy the orders to bring down the Indian flag had come from “heaven”, “implying thereby that the orders had emanated from a very high level of the Government of Pakistan” — the Pakistan Foreign Minister was after all ZA Bhutto and his Foreign Secretary the anti-Hindu Aziz Ahmed. Decades later the Indian journalist MJ Akbar would note the Pakistan army website itself asserting it would fly the Pakistan flag from Delhi’s Red Fort! It has not been India denying the sovereignty of Pakistan but vice versa.

On 2 October 1965, a day after the Note Verbale was received, the Pakistan Government kindly permitted the Indian mission to send messages by code again and not only en clair.

As noted earlier, the Karachi Mission under Kewal Singh had destroyed its code books and cyphers, and PN Kaul had been angry when Delhi eventually remembered them and sent a message in code they could no longer read! MKRoy, PN Ojha and others in Dhaka had managed to keep their codes though presumably Karachi would still not be able to read their encrypted communications, and messages had to be sent via London or Delhi (as they were).

13. Myanmar’s help: My sister & I leave via Rangoon

Meanwhile, MK Roy had asked the Indian Embassy in Rangoon to ask Delhi to restart communications through them:

On 6 October, MKRoy visited the Myanmar Consul General seeking and receiving diplomatic help with restarting a diplomatic courier service from East Pakistan to India via Rangoon:

It succeeded. Once AK Ray had returned to his Dhaka post on 16 October, my father on 31 October carrying the first diplomatic bag after the war flew my older sister and myself out of Dhaka in a Pakistani passenger aircraft to Chittagong and then Rangoon. I remember bristling at the (friendly) East Pakistan Government officials we met in Chittagong, then lunching at the home in Rangoon of my father’s cousin, Shanti Ganguly — and how we *rejoiced* when we finally entered our very own Indian Airlines plane taking us from Rangoon back to India! That concluded my personal 1965 war!

My father was much commended by M A Husain, Secretary in the Foreign Ministry in Delhi — whose own brother or cousin happened to the Pakistan envoy in Delhi during the war! MK Roy’s name was mentioned for the Padma Shri (an exceptional honour for a serving civil servant at the time) for his leadership in Dhaka during the war — for some reason, probably bureaucratic viciousness among his colleagues, he did not get it. But he was rewarded: with splendid Stockholm! Important roles followed in Odessa, and especially Paris in 1971 during Indira Gandhi’s visit trying to prevent the Bangladesh war. PN Haksar himself sent him, asking him in Delhi “Can you go to Paris?” — a rhetorical question if ever there was one. In Paris, the emerging Bangladesh loomed high, both with defecting East Pakistani diplomats and the visiting Bangladesh Government-in-Exile, as well as with air-lifting French aid for the refugees from the Pakistani atrocities. In Paris too I recall Kewal Singh, then ambassador in West Germany, visiting us, and as soon as Kewal Singh became Foreign Secretary, MK Roy went as ambassador to Helsinki, his last appointment as a diplomat: a productive exciting career that had commenced in Tehran, Ottawa and Vancouver, and Colombo, before the war experience in Dhaka.

14. Indian treatment of Pakistan diplomats “by the book”

15. November 1965 Indian protests to Pakistan Govt

On 4 November 1965, India lodged a formal protest with the Pakistani envoy in Delhi about the outrageous treatment of Indian diplomats, staff and families in Dhaka during the war.

16. Further analysis & conclusions

(NB this is a draft incomplete document still in process of being published, marking 7 November 2015 as MK Roy’s Birth Centenary)

Leave a comment