How the India-Bangladesh Enclaves Problem Was Jump-Started in 2007 Towards its 2015 Solution: A Case Study of Academic Impact on Policy

June 8, 2015 — drsubrotoroyPakistan’s & India’s Illusions of Power (Psychosis vs Vanity)

March 3, 2015 — drsubrotoroyPreface: This paper culminates my line of argument since our University of Hawaii Pakistan book in the mid 1980s, through my work on the Kashmir problem in the 1990s, published in The Statesman in 2005/2006 etc and in my undelivered Lahore lectures of 2011. https://independentindian.com/2011/10/13/my-seventy-one-notes-at-facebook-etc-on-kashmir-pakistan-and-of-course-india-listed-thanks-to-jd/ The paper has faced resistance from both Indian and Pakistani newspapers for obvious reasons. I would like to especially thank Beena Sarwar and Gita Sahgal in recent weeks for helpful comments. (And Frank Hahn, immediately saw when I mentioned it to him in 2004 that my solution was Pareto-improving…etc)

The *Bulletin of Atomic Scientists* recently reported an Urdu book *Taqat ka Sarab* (‘*Illusion of Power*) published in Pakistan in December 2014 edited by the physicist Dr AH Nayyar. The book “aims to educate Pakistanis about the attitudes of their leadership toward nuclear weapons”. It says “Pakistan’s people have come to believe that the successful acquisition of nuclear capability means that their nation’s security is forever ensured”. Pakistani politicians, scientists and officials who created these weapons have used them to justify a “right to unlimited authority for ruling over Pakistan”. “Consequently, free discussion and honest opinion about nuclear weapons have been nearly prohibited, under the premise that any such talk poses a basic threat to national security.”

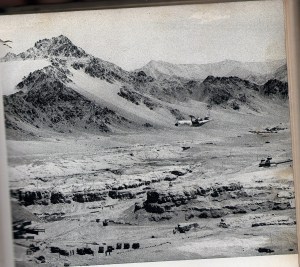

Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s order to Indian forces to cross the Punjab border towards Lahore in 1965 in response to President Ayub Khan’s attack in Kashmir genuinely shocked Pakistan’s political and military establishment at the time. It may have continued to do so ever since. Everyone in Lahore for those few days in September 1965 was ready to battle the invasion of infidel India considered imminent when Indian forces reached the Ichogil canal.

“Hindu-dominated India wants to occupy us and destroy the Pakistan Principle for which our martyrs died” has been the constantly heard Pakistani refrain. After 1965 it did not take long for Pakistan, via the ignominy of the 1971 surrender in Dhaka, to acquire by any means the technology to develop its own nuclear weapons, even under the noses of its American friends.

Now Pakistan is said to have some 110 nuclear warheads, mostly in a disassembled state but with a few on fighter-jets in hidden air-bases in Balochistan (made by the USA decades ago) always at the ready, waiting for that Indian attack that will never come. It may all have been psychotic delusion.

India has never initiated hostilities against Pakistan. Not once. Not in 1947, 1965, 1971, 1999, 2008.

In 1971 India undoubtedly supported the Mukti Bahini, and I myself, as a schoolboy distributing supplies to refugees from East Pakistan/Bangladesh, was personally witness to Indian military involvement as of August 1971. Even so, hostilities between the countries formally began on 3 December 1971 with the surprise Pakistani air attack on Indian bases in Punjab and UP.

Though India has never attacked first, the myth continues in Pakistan that wicked Hindu-dominated India wants to attack and suppress their country. What is closer to the truth is that the New Delhi elite is barely able to run New Delhi, and the last place on earth they would want to run is Pakistan.

On our Indian side, the Indian military has been allowed a budgetary carte blanche for decades, especially with foreign exchange resources. (Finance Minister Arun Jaitley on 28 February 2015 has allocated some 2,467 billion INR to the military.)

Despite our vast spending, a band of Lashkar-e-Tayyaba terrorists tyrannized Mumbai for days on end while we seem perpetually without strategy against the People’s Republic of China’s recurrent provocations.

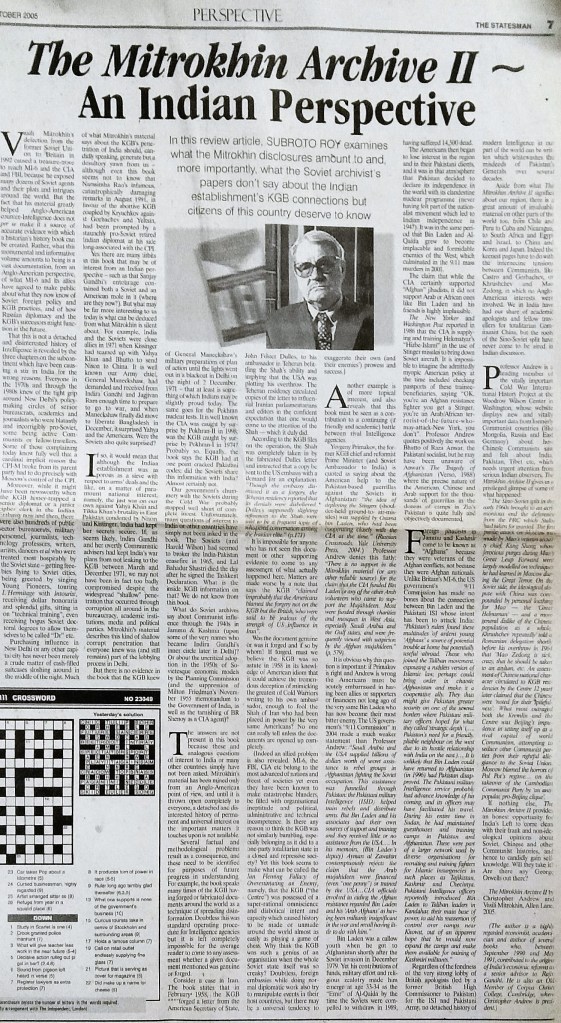

The two world powers with traditional interests in India — Russia and Britain — place their long-term agents in Delhi’s high politics and places with impunity, getting done all they need to in particular cases. The USA, France, Israel and others follow suit – all mainly to do with selling India very expensive military weapons, aircraft etc. that they have in excess inventory. India now has the notorious distinction of being the world’s largest weapons’ importer.

Yet we are hardly a trading or monetary superpower. We have large current account and budgetary deficits, and we are essentially buying whatever weapons, aircraft, shopping malls etc. that we do on foreign credit that we may or may not have. (Pakistan does the same.)

India’s illusions of power have to do with boasting a very large military that can take on the imperialists. We do not realize the New Imperialism that may control Delhi is not of a Clive or Dupleix but of clandestine or open foreign lobbyists and agents who get done what their masters need to have done on a case-by-case basis. The result is a corrosion of Indian power, sovereignty, and credit, little by little, and may lead to a collapse or grave crisis in the future. Even the BJP/RSS Government of Mr Modi (let aside the Sonia-Manmohan Congress and official Communists) may not realize how it all came about.

The way forward for both Pakistan and India is to seek to break the impasse between ourselves.

And there is no doubt the root problem remains Kashmir, and the hysteria and terrorism it has spawned over the years. A resolution of these fundamental issues calls for some hard scholarship, political vision and guts. The vapid gassing of stray bureaucrats, journalists, diplomats or generals has gotten everyone precisely nowhere thus far.

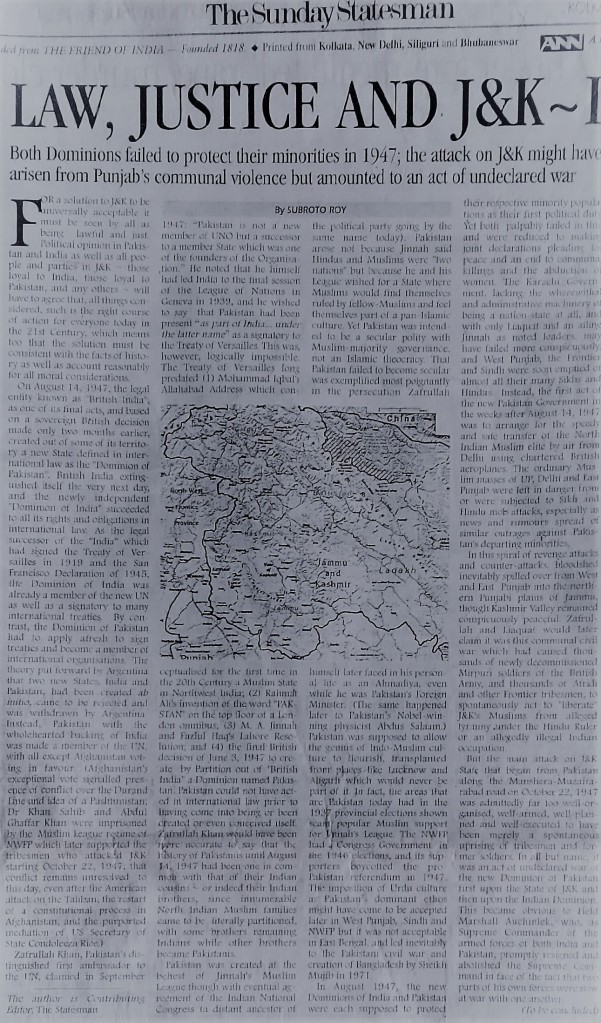

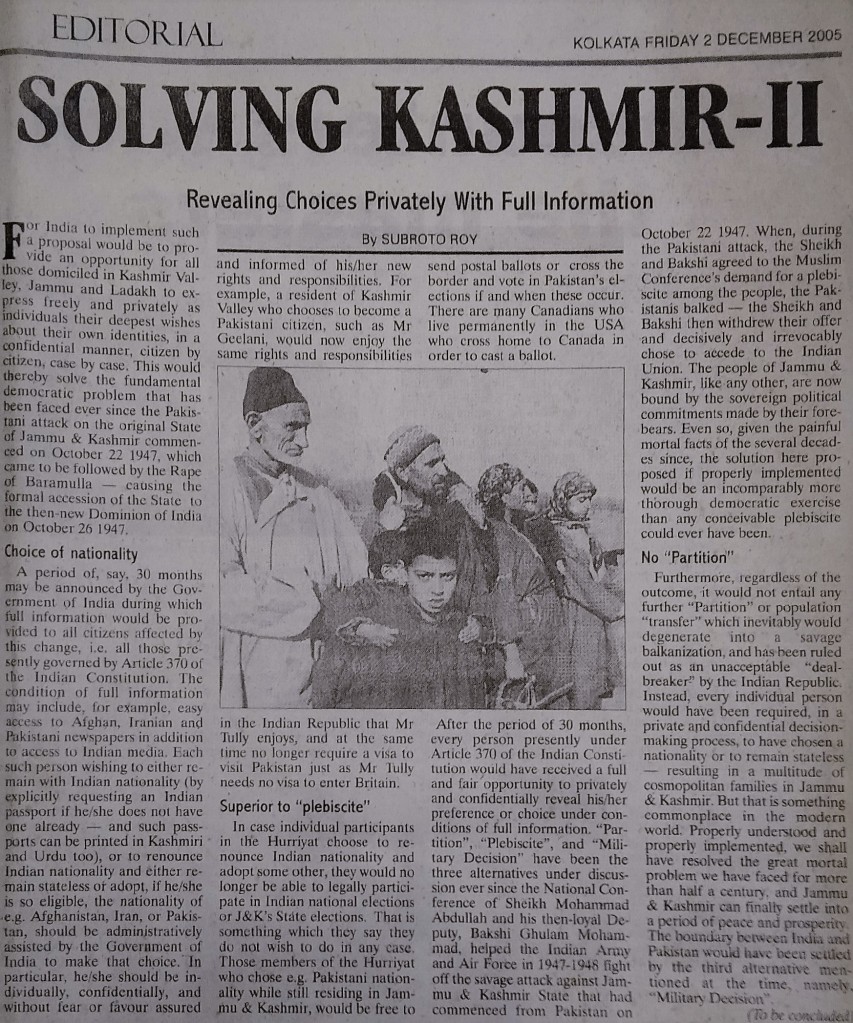

I have argued at length in previous publications that the *de facto* boundary that was the Ceasefire Line in 1949, and was later renamed the Line of Control in 1972, is indeed also the *de jure* boundary between India and Pakistan.

Jammu & Kashmir came into existence as a legal entity on 16 March 1846 under the Dogra Gulab Singh, friend of the British during the Sikh wars, and a protégé earlier of the great Sikh Ranjit Singh.

Dogra J&K ended its existence as an entity recognized in international law on 15 August 1947. (Hari Singh, the fourth and last Dogra ruler where Gulab Singh had been the first, desperately sought Clement Attlee’s recognition but did not get it.) Thanks to British legal confusion, negligence or cunning, the territory of what had been known as Dogra Jammu & Kashmir became sovereign-less or ownerless territory in international law on that date, with the creation of the new Pakistan and new India.

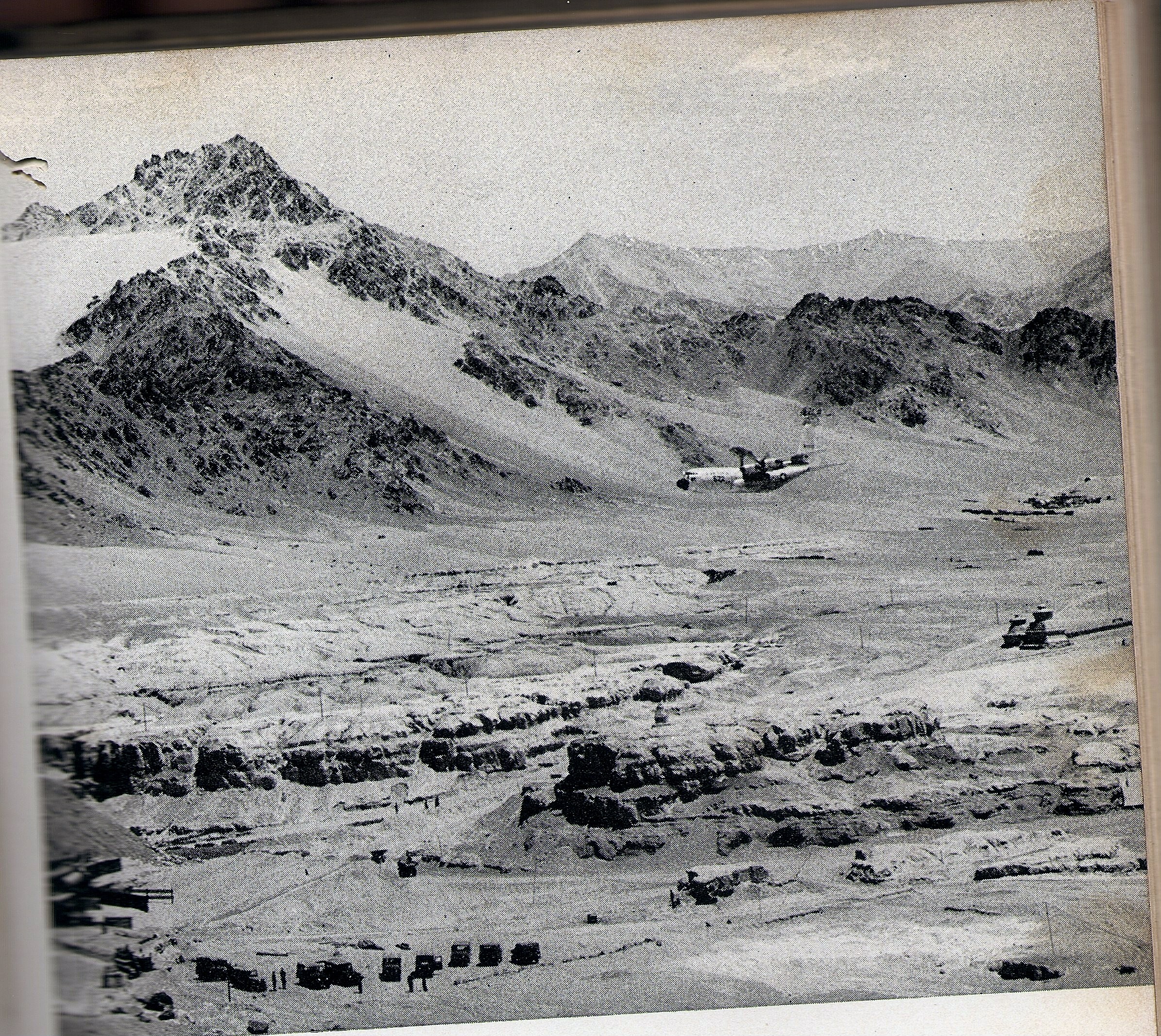

The new Pakistan as of August-September 1947 immediately started to plan to take the territory by force, and sought to implement that plan as of 22 October. Had the Pakistani attackers not stopped to indulge in the Rape of Baramullah, they would have taken Srinagar airport by 26 October, and there would have been no Indian defence of the territory possible. As matters turned out, the ownerless territory of what had been Dogra Jammu & Kashmir came to be divided by “military decision” (to use the UN’s term) between the new Pakistan and new India. Kargil and Drass were taken by Pakistan and then lost. Skardu was held by India and later lost. Neither military ever since is going to permit the other to take an inch from itself either by war or by diplomacy.

The *de facto* boundary over ownerless territory divided by military force is the *de jure* boundary in the Roman law that underlies all international law. Once both sides recognize that properly, we may proceed to the next stages.

On the Pakistani side, recognizing Indian sovereignty over Indian territory in what had been J&K requires stamping out the LeT etc – perhaps not so much by force as by explaining to them that the fight is over, permanently. There is no jihad against India now or ever. Indian territory is not dar-ul-harb but dar-ul-aman: where more than one hundred million Muslim citizens of India freely and peacefully practice their faith.

On the Indian side, if, say, SAS Geelani and friends, under conditions of individual privacy, security and full information, wish to renounce Indian nationality, become stateless, and apply for some other nationality (like Pakistani or Afghan or Iranian) while continuing to live lawfully and law-abidingly on Indian territory, do we have a problem with that? We can’t really. The expatriate children of the Indian elite have renounced Indian nationality in America, Britain, Australia etc upon far weaker principles or beliefs. India has many foreign nationals living permanently on its territory peacefully and law-abidingly (Sir Mark Tully perhaps the most notable) and can add a few more.

The road would be gradually opened for an exchange of consulates between India and Pakistan in Srinagar and Muzaffarabad (leave aside vice-consulates or tourist offices in Jammu, Gilgit, Skardu, Leh). And the remaining Hurriyat, as new Pakistani nationals living in India, can visit the Pakistani consul in Srinagar for tea every day if they wish, to discuss Pakistani matters like Afridi’s cricket or Bilawal’s politics or whatever.

The militaries and potentially powerful economies on both sides could then proceed towards real strength and cooperation, having dispelled their current illusions of power.

One of the men Rajiv introduced me to on 25-9-1990 at 10 JanPath (No, Rajiv did not realize who he was…) 2023

July 3, 2014 — drsubrotoroyMuch as I might love Russia, England, France, America, I despise their spies & local agents affecting poor India’s policies: Memo to PM Modi, Mr Jaitley, Mr Doval & the new Govt. of India: Beware of Delhi’s sleeper agents, lobbyists & other dalals (2014)

1 July 2014

Dear Bibek,

The very elderly man I refer to as “Sonia’s Lying Courtier” herein

https://independentindian.com/2007/11/25/sonias-lying-courtier/

is someone who has known you, leading up to your appointment as Director at Sonia’s “Rajiv Gandhi Institute” and later. He has now published a purported memoir whose main aim is to conceal his Soviet connections during the Brezhnev era 1960s-1970s, besides trying to rub my name out from my role with Rajiv in 1990-1991. The woman journalist in Delhi who is named as having ghost-written his new book is someone you know quite well too.

The man was someone whom I worked with and who was introduced to me by Rajiv Gandhi on 25/9/1990, a Soviet trained “technocrat” who had inveigled himself into Rajiv’s circle as he had been a favoured one of Indira (presumably via PN Haksar) when he returned from the USSR. He was also the link explaining, again via PN Haksar, how Manmohan first became FM in 1991 after Rajiv’s assassination, then how Manmohan came to Sonia’s notice and attention, and was later crucial in the so-called Rajiv Gandhi Foundation and in the formation of Sonia’s so-called National Advisory Council.

His mandate was to keep INC policies predictable and agreeable in the areas of Soviet/Russian interest, in which he seems to have succeeded during the Sonia-Manmohan regime.

He found me an unknown force, and worked to edge me out, despite the fact the 25/9/90 group was formed by Rajiv as a sounding-board for the perestroika-for-India project I led in America since 1986 and which I brought to Rajiv the week before on 18/9/90…

I send this to you as a word of caution as you are clearly close to Mr Modi and Mr Doval, yet none of you may know the man’s background and intent, even in his dotage. Certainly the purported memoir written by the woman journalist is something whose main aim is to conceal the man’s Soviet/Russian background. Had it been an honest intent, he would have had no need to conceal any of this but would have addressed his own Russian experience openly and squarely. He may have had his impact already with the new Government, I do not know.

For myself, I have been openly rather pro-Russia on the merits of the current Ukraine issue, but, as you will appreciate, I despise any kind of deep foreign agent seeking to control Indian policy in long-term concealment.

Cordially

Suby Roy

Sonia’s Lying Courtier with Postscript 25 Nov 2007, & Addendum 30 June 2014

30th June 2014

“Sonia’s Lying Courtier” (see below) has now lied again! In a ghost-written 2014 book published by a prominent publisher in Delhi!

He has so skilfully lied about himself the ghost writer was probably left in the dark too about the truth.

**The largest concealment has to do with his Soviet connection: he is fluent in Russian, lived as a privileged guest of the state there, and before returning to the Indian public sector was awarded in the early 1970s a Soviet degree, supposedly an earned doctorate in Soviet style management!**

How do I know? He told me so personally! His Soviet degree is what allowed himself to pass off as a “Dr” in Delhi power-circles for decades, as did many others who were planted in that era. He has also lied about himself and Rajiv Gandhi in 1990-1991, and hence he has lied about me indirectly.

In 2007 I was gentle in my exposure of his mendacity because of his advanced age. Now it is more and more clear to me that exposing this directly may be the one way for Sonia and her son to realise how they, and hence the Congress party, were themselves influenced without knowing it for years…

25 November 2007

Two Sundays ago in an English-language Indian newspaper, an elderly man in his 80s, advertised as being “the Gandhi family’s favourite technocrat” published some deliberate falsehoods about events in Delhi 17 years ago surrounding Rajiv Gandhi’s last months. I wrote at once to the man, let me call him Mr C, asking him to correct the falsehoods since, after all, it was possible he had stated them inadvertently or thoughtlessly or through faulty memory. He did not do so. I then wrote to a friend of his, a Congress Party MP from his State, who should be expected to know the truth, and I suggested to him that he intercede with his friend to make the corrections, since I did not wish, if at all possible, to be compelled to call an elderly man a liar in public.

That did not happen either and hence I am, with sadness and regret, compelled to call Mr C a liar.

The newspaper article reported that Mr C’s “relationship with Rajiv (Gandhi) would become closer when (Rajiv) was out of power” and that Mr C “was part of a group that brainstormed with Rajiv every day on a different subject”. Mr C has reportedly said Rajiv’s “learning period came after he left his job” as PM, and “the others (in the group)” were Mr A, Mr B, Mr D, Mr E “and Manmohan Singh” (italics added).

In reality, Mr C was a retired pro-USSR bureaucrat aged in his late 60s in September 1990 when Rajiv Gandhi was Leader of the Opposition and Congress President. Manmohan Singh was an about-to-retire bureaucrat who in September 1990 was not physically present in India, having been working for Julius Nyerere of Tanzania for several years.

On 18 September 1990, upon recommendation of Siddhartha Shankar Ray, Rajiv Gandhi met me at 10 Janpath, where I handed him a copy of the unpublished results of an academic “perestroika-for-India” project I had led at the University of Hawaii since 1986. The story of that encounter has been told first on July 31-August 2 1991 in The Statesman, then in the October 2001 issue of Freedom First, then in January 6-8 2006, September 23-24 2007 in The Statesman, and most recently in The Statesman Festival Volume 2007. The last of these speaks most fully yet of my warnings against Rajiv’s vulnerability to assassination; this document in unpublished form was sent by me to Rajiv’s friend, Mr Suman Dubey in July 2005, who forwarded it with my permission to the family of Rajiv Gandhi.

It was at the 18 September 1990 meeting that I suggested to Rajiv that he should plan to have a modern election manifesto written. The next day, 19 September, I was asked by Rajiv’s assistant V George to stay in Delhi for a few days as Mr Gandhi wished me to meet some people. I was not told whom I was to meet but that there would be a meeting on Monday, 24th September. On Saturday, the Monday meeting was postponed to Tuesday 25th September because one of the persons had not been able to get a flight into Delhi. I pressed to know what was going on, and was told I would meet Mr A, Mr B, Mr C and Mr D. It turned out later Mr A was the person who could not fly in from Hyderabad.

The group (excluding Mr B who failed to turn up because his servant had failed to give him the right message) met Rajiv at 10 Janpath in the afternoon of 25th September. We were asked by Rajiv to draft technical aspects of a modern manifesto for an election that was to be expected in April 1991. The documents I had given Rajiv a week earlier were distributed to the group. The full story of what transpired has been told in my previous publications.

Mr C was ingratiating towards me after that first meeting with Rajiv and insisted on giving me a ride in his car which he told me was the very first Maruti ever manufactured. He flattered me needlessly by saying that my PhD (in economics from Cambridge University) was real whereas his own doctoral degree had been from a dubious management institute of the USSR. (Handling out such doctoral degrees was apparently a standard Soviet way of gaining influence.) Mr C has not stated in public how his claim to the title of “Dr” arises.

Following that 25 September 1990 meeting, Mr C did absolutely nothing for several months towards the purpose Rajiv had set us, stating he was very busy with private business in his home-state where he flew to immediately. Mr D went abroad and was later hit by severe illness. Mr B, Mr A and I met for luncheon at New Delhi’s Andhra Bhavan where the former explained how he had missed the initial meeting. Then Mr B said he was very busy with his house-construction, and Mr A said he was very busy with finishing a book for his publishers on Indian defence, and both begged off, like Mr C and Mr D, from any of the work that Rajiv had explicitly set our group. My work and meeting with Rajiv in October 1990 has been reported previously.

Mr C has not merely suppressed my name from the group in what he has published in the newspaper article two Sundays ago, he has stated he met Rajiv as part of such a group “every day on a different subject”, another falsehood. The next meeting of the group with Rajiv was in fact only in December 1990, when the Chandrashekhar Government was discussed. I was called by telephone in the USA by Rajiv’s assistant V George but I was unable to attend, and was briefed later about it by Mr A.

When new elections were finally announced in March 1991, Mr C brought in Mr E into the group in my absence (so he told me), perhaps in the hope I would remain absent. But I returned to Delhi and between March 18 1991 and March 22 1991, our group, including Mr E (who did have a genuine PhD), produced an agreed-upon document. That document was handed over by us together in a group to Rajiv Gandhi at 10 Janpath the next day, and also went to the official political manifesto committee of Narasimha Rao, Pranab Mukherjee and M. Solanki.

Our group, as appointed by Rajiv on 25 September 1990, came to an end with the submission of the desired document to Rajiv on 23 March 1991.

As for Manmohan Singh, contrary to Mr C’s falsehood, Manmohan Singh has himself truthfully said he was with the Nyerere project until November 1990, then joined Chandrashekhar’s PMO in December 1990 which he left in March 1991, that he had no meeting with Rajiv Gandhi prior to Rajiv’s assassination but rather did not in fact enter Indian politics at all until invited by Narasimha Rao several weeks later to be Finance Minister. In other words, Manmohan Singh himself is on record stating facts that demonstrate Mr C’s falsehood.

The economic policy sections of the document submitted to Rajiv on 23 March 1991 had been drafted largely by myself with support of Mr E and Mr D and Mr C as well. It was done over the objections of Mr B, who had challenged me by asking what Manmohan Singh would think of it. I had replied I had no idea what Manmohan Singh would think of it, saying I knew he had been out of the country on the Nyerere project for some years.

Mr C has deliberately excluded my name from the group and deliberately added Manmohan Singh’s instead. What explains this attempted falsification of facts – reminiscent of totalitarian practices in communist countries? Manmohan Singh was not involved by his own admission, and as Finance Minister told me so directly when he and I were introduced in Washington DC in September 1993 by Siddhartha Shankar Ray, then Indian Ambassador to the USA.

A possible explanation for Mr C’s mendacity is as follows: I have been recently publishing the fact that I repeatedly pleaded warnings that I (even as a layman on security issues) perceived Rajiv Gandhi to have been insecure and vulnerable to assassination. Mr C, Mr B and Mr A were among the main recipients of my warnings and my advice as to what we as a group, appointed by Rajiv, should have done towards protecting Rajiv better. They did nothing — though each of them was a senior man then aged in his late 60s at the time and fully familiar with Delhi’s workings while I was a 35 year old newcomer. After Rajiv was assassinated, I was disgusted with what I had seen of the Congress Party and Delhi, and did not return except to meet Rajiv’s widow once in December 1991 to give her a copy of a tape in which her late husband’s voice was recorded in conversations with me during the Gulf War.

Mr C has inveigled himself into Sonia Gandhi’s coterie – while Manmohan Singh went from being mentioned in our group by Mr B to becoming Narasimha Rao’s Finance Minister and Sonia Gandhi’s Prime Minister. If Rajiv had not been assassinated, Sonia Gandhi would have been merely a happy grandmother today and not India’s purported ruler. India would also have likely not have been the macroeconomic and political mess that the mendacious people around Sonia Gandhi like Mr C have now led it towards.

POSTSCRIPT: The Congress MP was kind enough to write in shortly afterwards; he confirmed he “recognize(d) that Rajivji did indeed consult you in 1990-1991 about the future direction of economic policy.” A truth is told and, furthermore, the set of genuine Rajivists in the present Congress Party is identified as non-null.

Pakistan’s Point of View (Or Points of View) on Kashmir: My As Yet Undelivered Lahore Lecture–Part I

November 22, 2011 — drsubrotoroyPreface

27 April 2015 from Twitter: “My Pakistani hosts never managed to go thru w their 2010/11 invitation I speak in Lahore on Kashmir. After #SabeenMahmud s murder, I decline”

October 2015 from Twitter: I have started a quite thorough critique under #kasuri etc at Twitter of the extremely peculiar free publicity given in Delhi and Mumbai power circles to the dressed up (and false) ISI/Hurriyat narrative of KM Kasuri; the Musharraf “demilitarisation/borderless” idea that Mr Kasuri promotes is originally mine from our Pakistan book in America in the 1980s, which I brought to the attention of both sides (and the USA) in Washington in 1993 but which I myself later rejected as naive and ignorant after the Pakistani aggression in Kargil in 1999, especially the murder of Lt Kalia and his platoon as POWs. https://independentindian.com/2006/12/15/what-to-tell-musharraf-peace-is-impossible-without-non-aggressive-pakistani-intentions/ https://independentindian.com/2008/11/15/of-a-new-new-delhi-myth-and-the-success-of-the-university-of-hawaii-1986-1992-pakistan-project/

see too https://independentindian.com/2011/10/13/my-seventy-one-notes-at-facebook-etc-on-kashmir-pakistan-and-of-course-india-listed-thanks-to-jd/

I have also now made clear how and why my Lahore lecture (confirmed by the Pakistani envoy to Delhi personally phoning me of his own accord at home on 3 March 2011, followed the next day by the Indian Foreign Secretary phoning to give me an appointment to brief her about my talk upon my return) came to be sabotaged by two Pakistanis and two Indian politicians associated with them. (Both of the Indian politicians had bad karma catch up immediately afterwards!)

Original Preface 22 November 2011: Exactly a year ago, in late October-November 2010, I received a very kind invitation from the Lahore Oxford and Cambridge Society to speak there on this subject. Mid March 2011 was a tentative date for this lecture from which the text below is dated. The lecture has yet to take place for various reasons but as there is demand for its content, I am releasing the part which was due to be released in any case to my Pakistani hosts ahead of time — after all, it would have been presumptuous of me to seek to speak in Lahore on Pakistan’s viewpoint on Kashmir, hence I instead planned to release my understanding of that point of view ahead of time and open it to the criticism of my hosts. The structure of the remainder of the talk may be surmised too from the Contents. The text and argument are mine entirely, the subject of more than 25 years of research and reflection, and are under consideration of publication as a book by Continuum of London and New York. If you would like to comment, please feel free to do so, if you would like to refer to it in an online publication, please give this link, if you would like to refer to it in a paper-publication, please email me. Like other material at my site, it is open to the Fair Use rule of normal scholarship.

On the Alternative Theories of Pakistan and India about Jammu & Kashmir (And the One and Only Way These May Be Peacefully Reconciled): An Exercise in Economics, Politics, Moral Philosophy & Jurisprudence

by

Subroto (Suby) Roy

Lecture to the Oxford and Cambridge Society of Lahore

March 14, 2011 (tentative)

“What is the use of studying philosophy if all that does for you is to enable you to talk with some plausibility about some abstruse questions of logic, etc., & if it does not improve your thinking about the important questions of everyday life?” Wittgenstein, letter to Malcolm, 1944

“India is the greatest Muslim country in the world.”

Sir Muhammad Iqbal, 1930, Presidential Address to the Muslim League, Allahabad

“Where be these enemies?… See, what a scourge is laid upon your hate,… all are punish’d.” Shakespeare

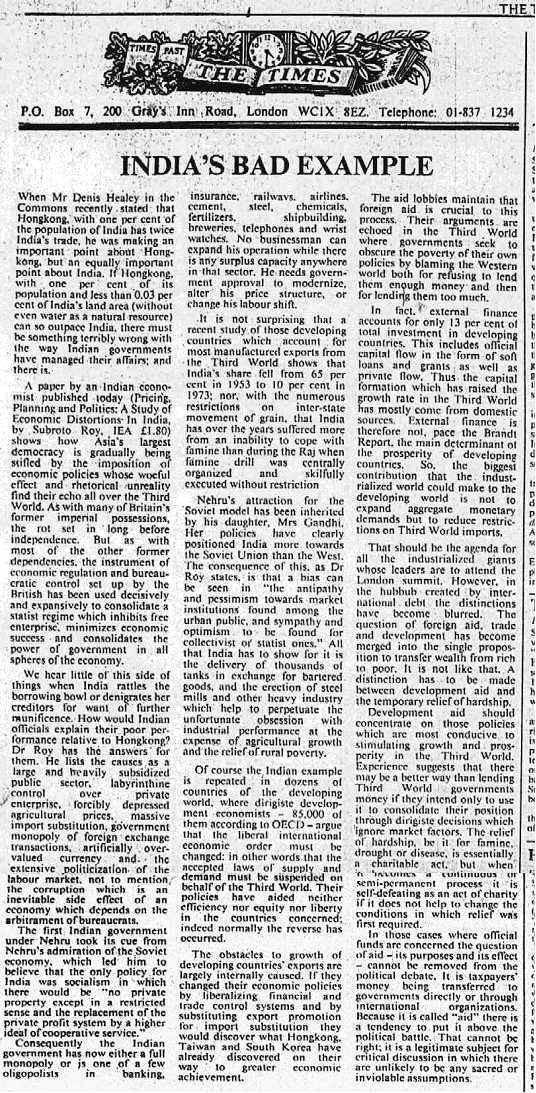

Dr Roy’s published works include Philosophy of Economics: On the Scope of Reason in Economic Inquiry (London & New York: Routledge, 1989, 1991); Pricing, Planning & Politics: A Study of Economic Distortions in India (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 1984); and, edited with WE James, Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s (Hawaii MS 1989, Sage 1992) & Foundations of Pakistan’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s (Hawaii MS 1989, Sage 1992, OUP Karachi 1993); and, edited with John Clarke, Margaret Thatcher’s Revolution: How it Happened and What it Meant (London & New York: Continuum 2005). He graduated in 1976 with a first from the London School of Economics in mathematical economics, and received the PhD in economics at Cambridge in 1982 under Professor Frank Hahn for the thesis “On liberty & economic growth: preface to a philosophy for India”. In the United States for 16 years he was privileged to count as friends Professors James Buchanan, Milton Friedman, TW Schultz, Max Black and Sidney Alexander. From September 18 1990 he was an adviser to Rajiv Gandhi and contributed to the origins of India’s 1991 economic reform. He blogs at http://www.independentindian.com.

CONTENTS

Part I

-

Introduction

-

Pakistan’s Point of View (or Points of View)

(a) 1930 Sir Muhammad Iqbal

(b) 1933-1948 Chaudhury Rahmat Ali

(c) 1937-1941 Sir Sikander Hayat Khan

(d) 1937-1947 Quad-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah

(e) 1940s et seq Maulana Abul Ala Maudoodi

(f) 1947-1950 Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, 1966 President Ayub Khan, 2005 Govt of Pakistan, 2007 President Musharraf, 2008 FM Qureshi, 2011 Kashmir Day

Part II

-

India’s Point of View: British Negligence/Indifference during the Transfer of Power, A Case of Misgovernance in the Chaotic Aftermath of World War II

(a) Rhetoric: Whose Pakistan? Which Kashmir?

(b) Law: (i) Liaquat-Zafrullah-Abdullah-Nehru United in Error Over the Second Treaty of Amritsar! Dogra J&K subsists Mar 16 1846-Oct 22 1947. Aggression, Anarchy, Annexations: The LOC as De Facto Boundary by Military Decision Since Jan 1 1949. (ii) Legal Error & Confusion Generated by 12 May 1946 Memorandum. (iii) War: Dogra J&K attacked by Pakistan, defended by India: Invasion, Mutiny, Secession of “Azad Kashmir” & Gilgit, Rape of Baramulla, Siege of Skardu.

-

Politics: What is to be Done? Towards Truths, Normalisation, Peace in the 21st Century

The Present Situation is Abnormal & Intolerable. There May Be One (and Only One) Peacable Solution that is Feasible: Revealing Individual Choices Privately with Full Information & Security: Indian “Green Cards”/PIO-OCI status for Hurriyat et al: A Choice of Nationality (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran). Of Flags and Consulates in Srinagar & Gilgit etc: De Jure Recognition of the Boundary, Diplomatic Normalisation, Economic & Military Cooperation.

-

Appendices:

(a) History of Jammu & Kashmir until the Dogra Native State

(b) Pakistan’s Allies (including A Brief History of Gilgit)

(c) India’s Muslim Voices

(d) Pakistan’s Muslim Voices: An Excerpt from the Munir Report

Part I

1. Introduction

For a solution to Jammu & Kashmir to be universally acceptable it must be seen by all as being lawful and just. Political opinion across the subcontinent — in Pakistan, in India, among all people and parties in J&K, those loyal to India, those loyal to Pakistan, and any others — will have to agree that, all things considered, such is the right course of action for everyone today in the 21st Century, which means too that the solution must be consistent with the principal known facts of history as well as account reasonably for all moral considerations.

I claim to have found such a solution, indeed I shall even say it is the only such solution (in terms of theoretical economics, it is the unique solution) and plan with your permission to describe its main outlines at this distinguished gathering. I have not invented it overnight but it is something developed over a quarter century, milestones along the way being the books emerging from the University of Hawaii “perestroika” projects for India and Pakistan that I and the late WE James led 25 years ago, and a lecture I gave at Washington’s Heritage Foundation in June 1998, as well as sets of newspaper articles published between 2005 and 2008, one in Dawn of Karachi and others in The Statesman of New Delhi and Kolkata.

Before I start, allow me for a moment to remind just how complex and intractable the problem we face has been, and, therefore, quite how large my ambition is in claiming today to be able to resolve it.

“Kashmir is in the Supreme National Interest of Pakistan”, says Pakistan.

“Kashmir is an Integral Part of India”, says India.

“Kashmir is an Integral Part of Pakistan”, says Pakistan.

“Kashmir is in the Supreme National Interest of India”, says India.

And so it goes, in what over the decades has been all too often a Dialogue of the Deaf. How may such squarely opposed positions be reconciled without draining public resources even further through wasteful weaponry and confrontation of standing armies, or, what is worse, using these weapons and armies in war, plunging the subcontinent into an abyss of chaos and destruction for generations to come? How is it possible?

I shall suggest a road can be found only when we realize Pakistan, India and J&K each have been and are going to remain integral to one another — in their histories, their geographies, their economies and their societies. The only place they may need to differ, where we shall want them to differ, is their politics and political systems. We should not underestimate how much mutual hatred and mutual fear has arisen naturally on all sides over the decades as a result of bloodshed and suffering all around, and the fact must also be accounted for that people simply may not be in a calm-enough emotional state to want to be part of processes seeking resolution; at the same time, it bears to be remembered that although Pakistan and India have been at war more than once and war is always a very serious and awful thing, they have never actually declared war against the other nor have they ever broken diplomatic relations – in fact in some ways it has always seemed like some very long and protracted fraternal Civil War between us where we think we know one another so well and yet come to be surprised more by one another’s virtues than by one another’s vices.

Secondly, with any seemingly intractable problem, dialogue can stall or be aborted due to normal human failings of impatience or lack of good will or lack of good humour or lack of a scientific attitude towards finding facts, or plain mutual miscomprehension of one another’s points of view through ignorance or laziness or negligence. In case of Pakistan and India over J&K, there has been the further critical complication that we of this generation did not cause this problem — it has been something inherited by us from not even our fathers but our grandfathers! It is two generations old. Each side must respect the words and deeds of its forebears but also may have to frankly examine in a scientific spirit where errors of fact or judgment may have occurred back then. The antagonistic positions have changed only slightly over two generations, and one reason dialogue stalls or gets aborted today is because positions have become frozen for more than half a century and merely get repeated endlessly. On top of such frozen positions have been piled pile upon pile of further vast mortal complications: the 1965 War, the 1971 secession of East Pakistan, the 1999 Kargil War, the 2008 Mumbai massacres. Only cacophony results if we talk about everything at once, leaving the status quo of a dangerous expensive confrontation to continue.

I propose instead to focus as specifically and precisely as possible on how Jammu & Kashmir became a problem at all during those crucial decades alongside the processes of Indian Independence, World War II, the Pakistan Movement and creation of Pakistan, accompanied by the traumas and bloodshed of Partition.

Having addressed that — and it is only fair to forewarn this eminent Lahore audience that such a survey of words, deeds and events between the 1930s and 1950s tends to emerge in India’s favour — I propose to “fast-forward” to current times, where certain new facts on the ground appear much more adverse to India, and finally seek to ask what can and ought to be done, all things considered, today in the circumstances of the 21st Century. There are four central facts, let me for now call them Fact A, Fact B, Fact C and Fact D, which have to be accepted by both countries in good faith and a scientific spirit. Facts A and B are historical in nature; Pakistan has refused to accept them. Facts C and D are contemporary in nature; official political India and much of the Indian media too often have appeared wilfully blind to them. The moment all four facts come to be accepted by all, the way forward becomes clear. We have inherited this grave mortal problem which has so badly affected the ordinary people of J&K in the most terrible and unacceptable manner, but if we fail to understand and resolve it, our children and grandchildren will surely fail even worse — we may even leave them to cope with the waste and destruction of further needless war or confrontation, indeed with the end of the subcontinent as we have received and known it in our time.

2. Pakistan’s Point of View (Or Points of View)

1930 Sir Muhammad Iqbal

This audience will need no explanation why I start with Sir Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), the poetic and spiritual genius who in the 20th Century inspired the notion of a Muslim polity in NorthWestern India, whose seminal 1930 presidential speech to the Muslim League in Allahabad lay the foundation stone of the new country that was yet to be. He did not live to see Pakistan’s creation yet what may be called the “Pakistan Principle” was captured in his words:

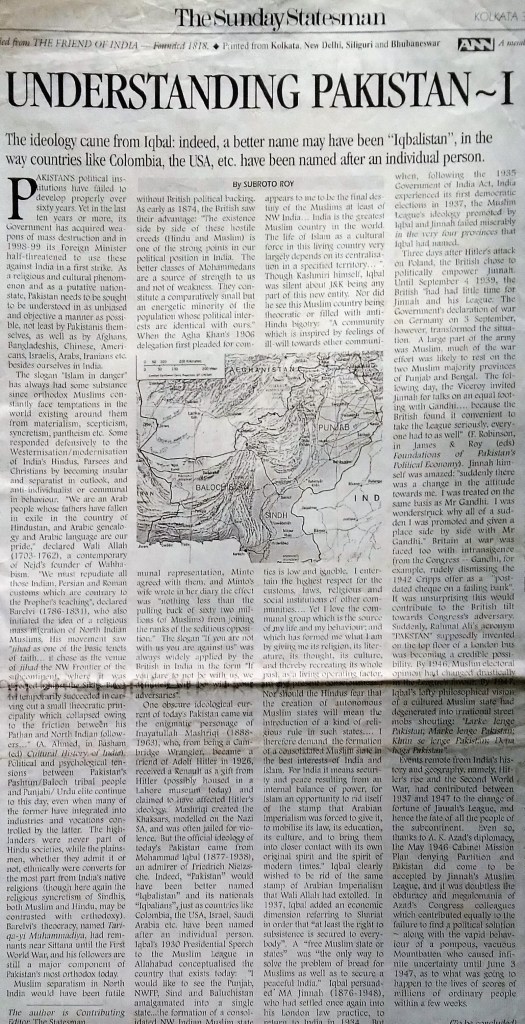

“I would like to see the Punjab, Northwest Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British Empire or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North West Indian Muslim state appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims at least of Northwest India… India is the greatest Muslim country in the world. The life of Islam as a cultural force in this living country very largely depends on its centralization in a specified territory”.

He did not see such a consolidated Muslim state being theocratic and certainly not one filled with bigotry or “Hate-Hindu” campaigns:

“A community which is inspired by feelings of ill-will towards other communities is low and ignoble. I entertain the highest respect for the customs, laws, religious and social institutions of other communities… Yet I love the communal group which is the source of my life and my behaviour… Nor should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states…. I therefore demand the formation of a consolidated Muslim state in the best interests of India and Islam. For India it means security and peace resulting from an internal balance of power, for Islam an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian Imperialism was forced to give it, to mobilise its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and the spirit of modern times.”[1]

Though Kashmiri himself, in fact a founding member of the “All-India Jammu & Kashmir Muslim Conference of Lahore and Simla”, and a hero and role model for the young Sheikh Abdullah (1905-1982), Allama Iqbal was explicitly silent about J&K being part of the new political entity he had come to imagine. I do not say he would not have wished it to be had he lived longer; what I am saying is that his original vision of the consolidated Muslim state which constitutes Pakistan today (after a Partitioned Punjab) did not include Jammu & Kashmir. Rather, it was focused on the politics of British India and did not mention the politics of Kashmir or any other of the so-called “Princely States” or “Native States” of “Indian India” who constituted some 1/3rd of the land mass and 1/4th of the population of the subcontinent. Twenty years ago I called this “The Paradox of Kashmir”, namely, that prior to 1947 J&K hardly seemed to appear in any discussion at all for a century, yet it has consumed almost all discussion and resources ever since.

Secondly, this audience will see better than I can the significance of Dr Iqbal’s saying the Muslim political state of his conception needed

“an opportunity to rid itself of the stamp that Arabian Imperialism was forced to give it”

and instead seek to

“mobilise its law, its education, its culture, and to bring them into closer contact with its own original spirit and the spirit of modern times”.

Dr Iqbal’s Pakistan Principle appears here the polar opposite of Pakistan’s 18th & 19th Century pre-history represented by Shah Waliullah (1703-1762)[2] saying

“We are an Arab people whose fathers have fallen in exile in the country of Hindustan, and Arabic genealogy and Arabic language are our pride”

or Sayyid Ahmed Barelwi (1786-1831) saying

“We must repudiate all those Indian, Persian and Roman customs which are contrary to the Prophet’s teaching”.[3]

Some 25 years after the Allahabad address, the Munir Report in 1954 echoed Dr Iqbal’s thought when it observed about medieval military conquests

“It is this brilliant achievement of the Arabian nomads …that makes the Musalman of today live in the past and yearn for the return of the glory that was Islam… Little does he understand that the forces which are pitted against him are entirely different from those against which early Islam had to fight… Nothing but a bold reorientation of Islam to separate the vital from the lifeless can preserve it as a World Idea and convert the Musalman into a citizen of the present and the future world from the archaic incongruity that he is today…” [4]

1933-1947 Chaudhury Rahmat Ali

Dr Iqbal’s young follower, the radical Cambridge pamphleteer Chaudhury Rahmat Ali (1895-1951) drew a picture not of Muslim tolerance and coexistence with Hindus in a peaceful India but of aggression towards Hindus and domination by Muslims over the subcontinent and Asia itself. Rahmat Ali had been inspired by Dr Iqbal’s call for a Muslim state in Northwest India but found it vague and was disappointed Iqbal had not pressed it at the Third Round Table Conference. In 1933, reportedly on the upper floor of a London omnibus, he invented for the then-imagined political entity the name “PAKSTAN”, P for his native Punjab, A for Afghania, K for Kashmir, S for Sind, and STAN for Balochistan. He sought a meeting with Mr Jinnah in London — “Jinnah disliked Rahmat Ali’s ideas and avoided meeting him”[5] but did meet him. There is a thesis yet to be written on how Europe’s inter-War ideologies affected political thinking on the subcontinent. Rahmat Ali’s vituperative views about Hindus were akin to others about Jews (and Muslims too) at the time, all models or counterfoils for one another in the fringes of Nazism. He referred to the Indian nationalist movement as a “British-Banya alliance”, declined to admit India had ever existed and personally renamed the subcontinent “Dinia” and the seas around it the “Pakian Sea”, the “Osmanian Sea” etc. He urged Sikhs to rise up in a “Sikhistan” and urged all non-Hindus to rise up in war against Hindus. Given the obscurity of his life before his arrival at Cambridge’s Emmanuel College, what experiences may have led him to such views are not known.

All this was anathema to Mr Jinnah, the secular constitutionalist embarrassed by a reactionary Muslim imperialism in that rapidly modernising era that was the middle of the 20th Century. When Rahmat Ali pressed the ‘Pakstan’ acronym, Mr Jinnah said Bengal was not in it and Muslim minority regions were absent. At this Chaudhury-Sahib produced a general scheme of Muslim domination all over the subcontinent: there would be “Pakstan” in the northwest including Kashmir, Delhi and Agra; “Bangistan” in Bengal; “Osmanistan” in Hyderabad; “Siddiquistan” in Bundelhand and Malwa; “Faruqistan” in Bihar and Orissa; “Haideristan” in UP; “Muinistan” in Rajasthan; “Maplistan” in Kerala; even “Safiistan” in “Western Ceylon” and “Nasaristan” in “Eastern Ceylon”, etc. In 1934 he published and widely circulated such a diagram among Muslims in Britain at the time. He was not invited to the Lahore Resolution which did not refer to Pakistan though came to be called the Pakistan Resolution. When he landed in the new Pakistan, he was apparently arrested and deported back and was never granted a Pakistan passport. From England, he turned his wrath upon the new government, condemning Mr Jinnah as treacherous and newly re-interpreting his acronym to refer to Punjab, Afghania, Kashmir, Iran, Sindh, Tukharistan (sic), Afghanistan, and Balochistan. The word “pak” coincidentally meant pure, so he began to speak of Muslims as “the Pak” i.e. “the pure” people, and of how the national destiny of the new Pakistan was to liberate “Pak” people everywhere, including the new India, and create a “Pak Commonwealth of Nations” stretching from Arabia to the Indies. The map he now drew placed the word “Punjab” over J&K, and saw an Asia dominated by this “Pak” empire. Shunned by officialdom of the new Pakistan, Chaudhury-Sahib was a tragic figure who died in poverty and obscurity during an influenza epidemic in 1951; the Master of Emmanuel College paid for his funeral and was apparently later reimbursed for this by the Government of Pakistan. In recent years he has undergone a restoration, and his grave at Cambridge has become a site of pilgrimage for ideologues, while his diagrams and writings have been reprinted in Pakistan’s newspapers as recently as February 2005.

1937-1941 Sir Sikander Hayat Khan

Chaudhary Rahmat Ali’s harshest critic at the time was the eminent statesman and Premier of Punjab Sir Sikander Hayat Khan (1892-1942), partner of the 1937 Sikander-Jinnah Pact, and an author of the Lahore Resolution. His statement of 11 March 1941 in the Punjab Legislative Assembly Debates is a classic:

“No Pakistan scheme was passed at Lahore… As for Pakistan schemes, Maulana Jamal-ud-Din’s is the earliest…Then there is the scheme which is attributed to the late Allama Iqbal of revered memory. He, however, never formulated any definite scheme but his writings and poems have given some people ground to think that Allama Iqbal desired the establishment of some sort of Pakistan. But it is not difficult to explode this theory and to prove conclusively that his conception of Islamic solidarity and universal brotherhood is not in conflict with Indian patriotism and is in fact quite different from the ideology now sought to be attributed to him by some enthusiasts… Then there is Chaudhuri Rahmat Ali’s scheme (*laughter*)…it was widely circulated in this country and… it was also given wide publicity at the time in a section of the British press. But there is another scheme…it was published in one of the British journals, I think Round Table, and was conceived by an Englishman…..the word Pakistan was not used at the League meeting and this term was not applied to (the League’s Lahore) resolution by anybody until the Hindu press had a brain-wave and dubbed it Pakistan…. The ignorant masses have now adopted the slogan provided by the short-sighted bigotry of the Hindu and Sikh press…they overlooked the fact that the word Pakistan might have an appeal – a strong appeal – for the Muslim masses. It is a catching phrase and it has caught popular imagination and has thus made confusion worse confounded…. So far as we in the Punjab are concerned, let me assure you that we will not countenance or accept any proposal that does not secure freedom for all (*cheers*). We do not desire that Muslims should domineer here, just as we do not want the Hindus to domineer where Muslims are in a minority. Now would we allow anybody or section to thwart us because Muslims happen to be in a majority in this province. We do not ask for freedom that there may be a Muslim Raj here and Hindu Raj elsewhere. If that is what Pakistan means I will have nothing to do with it. If Pakistan means unalloyed Muslim Raj in the Punjab then I will have nothing to do with it (*hear, hear*)…. If you want real freedom for the Punjab, that is to say a Punjab in which every community will have its due share in the economic and administrative fields as partners in a common concern, then that Punjab will not be Pakistan but just Punjab, land of the five rivers; Punjab is Punjab and will always remain Punjab whatever anybody may say (*cheers*). This, then, briefly is the future which I visualize for my province and for my country under any new constitution.

Intervention (Malik Barkat Ali): The Lahore resolution says the same thing.

Premier: Exactly; then why misinterpret it and try to mislead the masses?…”

1937-1947 Quad-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah

During the Third Round Table Conference, Dr Iqbal persuaded Mr Jinnah (1876-1948) to return to India; Mr Jinnah, from being settled again in his London law practice, did so in 1934. But following the 1935 Govt of India Act, the Muslim League failed badly when British India held its first elections in 1937 not only in Bengal and UP but in Punjab (one seat), NWFP and Sind.

World War II, like World War I a couple of brief decades earlier, then changed the political landscape completely. Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 and Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September. The next day, India’s British Viceroy (Linlithgow) granted Mr Jinnah the political parity with Congress that he had sought.[6] Professor Francis Robinson suggests that until 4 September 1939 the British

“had had little time for Jinnah and his League. The Government’s declaration of war on Germany on 3 September, however, transformed the situation. A large part of the army was Muslim, much of the war effort was likely to rest on the two Muslim majority provinces of Punjab and Bengal. The following day, the Viceroy invited Jinnah for talks on an equal footing with Gandhi…. As the Congress began to demand immediate independence, the Viceroy took to reassuring Jinnah that Muslim interests would be safeguarded in any constitutional change. Within a few months, he was urging the League to declare a constructive policy for the future, which was of course presented in the Lahore Resolution[7]…. In their August 1940 offer, the British confirmed for the benefit of Muslims that power would not be transferred against the will of any significant element in Indian life. And much the same confirmation was given in the Cripps offer nearly two years later…. Throughout the years 1940 to 1945, the British made no attempt to tease out the contradictions between the League’s two-nation theory, which asserted that Hindus and Muslims came from two different civilisations and therefore were two different nations, and the Lahore Resolution, which demanded that ‘Independent States’ should be constituted from the Muslim majority provinces of the NE and NW, thereby suggesting that Indian Muslims formed not just one nation but two. When in 1944 the governors of Punjab and Bengal urged such a move on the Viceroy, Wavell ignored them, pressing ahead instead with his own plan for an all-India conference at Simla. The result was to confirm, as never before in the eyes of leading Muslims in the majority provinces, the standing of Jinnah and the League. Thus, because the British found it convenient to take the League seriously, everyone had to as well—Congressmen, Unionists, Bengalis, and so on…”[8]

Mr Jinnah was himself amazed by the new British attitude towards him:

“(S)uddenly there was a change in the attitude towards me. I was treated on the same basis as Mr Gandhi. I was wonderstruck why all of a sudden I was promoted and given a place side by side with Mr Gandhi.”

Britain, threatened for its survival, faced an obdurate Indian leadership and even British socialists sympathetic to Indian aspirations grew cold (Gandhi dismissing the 1942 Cripps offer as a “post-dated cheque on a failing bank”). Official Britain’s loyalties had been consistently with those who had been loyal to them, and it was unsurprising there would be a tilt to empower Mr Jinnah soon making credible the real possibility of Pakistan.[9] By 1946, Britain was exhausted, pre-occupied with rationing, Berlin, refugee resettlement and countless other post-War problems — Britain had not been beaten in war but British imperialism was finished because of the War. Muslim opinion in British India had changed decisively in the League’s favour. But the subcontinent’s political processes were drastically spinning out of everyone’s control towards anarchy and blood-letting. Implementing a lofty vision of a cultured progressive consolidated Muslim state in India’s NorthWest descended into “Direct Action” with urban mobs shouting Larke lenge Pakistan; Marke lenge Pakistan; Khun se lenge Pakistan; Dena hoga Pakistan.[10]

We shall return to Mr Jinnah’s view on the legal position of the “Native Princes” of “Indian India” during this critical time, specifically J&K; here it is essential before proceeding only to record his own vision for the new Pakistan as recorded by the profoundly judicious report of Justice Munir and Justice Kayani a mere half dozen years later:

“Before the Partition, the first public picture of Pakistan that the Quaid-i-Azam gave to the world was in the course of an interview in New Delhi with Mr. Doon Campbell, Reuter’s Correspondent. The Quaid-i-Azam said that the new State would be a modern democratic State, with sovereignty resting in the people and the members of the new nation having equal rights of citizenship regardless of their religion, caste or creed. When Pakistan formally appeared on the map, the Quaid-i-Azam in his memorable speech of 11th August 1947 to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, while stating the principle on which the new State was to be founded, said:—‘All the same, in this division it was impossible to avoid the question of minorities being in one Dominion or the other. Now that was unavoidable. There is no other solution. Now what shall we do? Now, if we want to make this great State of Pakistan happy and prosperous we should wholly and solely concentrate on the well-being of the people, and specially of the masses and the poor. If you will work in co-operation, forgetting the past, burying the hatchet, you are bound to succeed. If you change your past and work together in a spirit that every one of you, no matter to what community he belongs, no matter what relations he had with you in the past, no matter what is his colour, caste or creed, is first, second and last a citizen of this State with equal rights, privileges and obligations., there will be no end to the progress you will make. “I cannot emphasise it too much. We should begin to work in that spirit and in course of time all these angularities of the majority and minority communities—the Hindu community and the Muslim community— because even as regards Muslims you have Pathana, Punjabis, Shias, Sunnis and so on and among the Hindus you have Brahmins, Vashnavas, Khatris, also Bengalis, Madrasis and so on—will vanish. Indeed if you ask me this has been the biggest hindrance in the way of India to attain its freedom and independence and but for this we would have been free peoples long long ago. No power can hold another nation, and specially a nation of 400 million souls in subjection; nobody could have conquered you, and even if it had happened, nobody could have continued its hold on you for any length of time but for this (Applause). Therefore, we must learn a lesson from this. You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed— that has nothing to do with the business of the State (Hear, hear). As you know, history shows that in England conditions sometime ago were much worse than those prevailing in India today. The Roman Catholics and the Protestants persecuted each other. Even now there are some States in existence where there are discriminations made and bars imposed against a particular class. Thank God we are not starting in those days. We are starting in the days when there is no discrimination, no distinction between one community and another, no discrimination between one caste or creed and another. We are starting with this fundamental principle that we are all citizens and equal citizens of one State (Loud applause). The people of England in course of time had to face the realities of the situation and had to discharge the responsibilities and burdens placed upon them by the Government of their country and they went through that fire step by step. Today you might say with justice that Roman Catholics and Protestants do not exist: what exists now is that every man is a citizen, an equal citizen, of Great Britain and they are all members of the nation. “Now, I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State’. The Quaid-i-Azam was the founder of Pakistan and the occasion on which he thus spoke was the first landmark in the history of Pakistan. The speech was intended both for his own people including non-Muslims and the world, and its object was to define as clearly as possible the ideal to the attainment of which the new State was to devote all its energies. There are repeated references in this speech to the bitterness of the past and an appeal to forget and change the past and to bury the hatchet. The future subject of the State is to be a citizen with equal rights, privileges and obligations, irrespective of colour, caste, creed or community. The word ‘nation’ is used more than once and religion is stated to have nothing to do with the business of the State and to be merely a matter of personal faith for the individual.”

1940s et seq Maulana Abul Ala Maudoodi, Amir Jama’at-i-Islami

The eminent theologian Maulana Abul Ala Maudoodi (1903-1979), founder of the Jama’at-i-Islami, had been opposed to the Pakistan Principle but once Pakistan was created he became the most eminent votary of an Islamic State, declaring:

“That the sovereignty in Pakistan belongs to God Almighty alone and that the Government of Pakistan shall administer the country as His agent”.

In such a view, Islam becomes

“the very antithesis of secular Western democracy. The philosophical foundation of Western democracy is the sovereignty of the people. Lawmaking is their prerogative and legislation must correspond to the mood and temper of their opinion… Islam… altogether repudiates the philosophy of popular sovereignty and rears its polity on the foundations of the sovereignty of God and the viceregency (Khilafat) of man.”

Maulana Maudoodi was asked by Justice Munir and Justice Kayani:

“Q.—Is a country on the border of dar-ul-Islam always qua an Islamic State in the position of dar-ul-harb ?

A.—No. In the absence of an agreement to the contrary, the Islamic State will be potentially at war with the non-Muslim neighbouring country. The non-Muslim country acquires the status of dar-ul-harb only after the Islamic State declares a formal war against it”.

“Q.—Is there a law of war in Islam?

A.—Yes.

Q.—Does it differ fundamentally from the modern International Law of war?

A.—These two systems are based on a fundamental difference.

Q.—What rights have non-Muslims who are taken prisoners of war in a jihad?

A.—The Islamic law on the point is that if the country of which these prisoners are nationals pays ransom, they will be released. An exchange of prisoners is also permitted. If neither of these alternatives is possible, the prisoners will be converted into slaves for ever. If any such person makes an offer to pay his ransom out of his own earnings, he will be permitted to collect the money necessary for the fidya (ransom).

Q.—Are you of the view that unless a Government assumes the form of an Islamic Government, any war declared by it is not a jihad?

A.—No. A war may be declared to be a jihad if it is declared by a national Government of Muslims in the legitimate interests of the State. I never expressed the opinion attributed to me in Ex. D. E. 12:— (translation)‘The question remains whether, even if the Government of Pakistan, in its present form and structure, terminates her treaties with the Indian Union and declares war against her, this war would fall under the definition of jihad? The opinion expressed by him in this behalf is quite correct. Until such time as the Government becomes Islamic by adopting the Islamic form of Government, to call any of its wars a jihad would be tantamount to describing the enlistment and fighting of a non-Muslim on the side of the Azad Kashmir forces jihad and his death martyrdom. What the Maulana means is that, in the presence of treaties, it is against Shari’at, if the Government or its people participate in such a war. If the Government terminates the treaties and declares war, even then the war started by Government would not be termed jihad unless the Government becomes Islamic’.

….

“Q.—If we have this form of Islamic Government in Pakistan, will you permit Hindus to base their Constitution on the basis of their own religion?

A—Certainly. I should have no objection even if the Muslims of India are treated in that form of Government as shudras and malishes and Manu’s laws are applied to them, depriving them of all share in the Government and the rights of a citizen. In fact such a state of affairs already exists in India.”

.…

“Q.—What will be the duty of the Muslims in India in case of war between India and Pakistan?

A.—Their duty is obvious, and that is not to fight against Pakistan or to do anything injurious to the safety of Pakistan.”

1947-1950 PM Liaquat Ali Khan, 1966 Gen Ayub Khan, 2005 Govt of Pakistan et seq

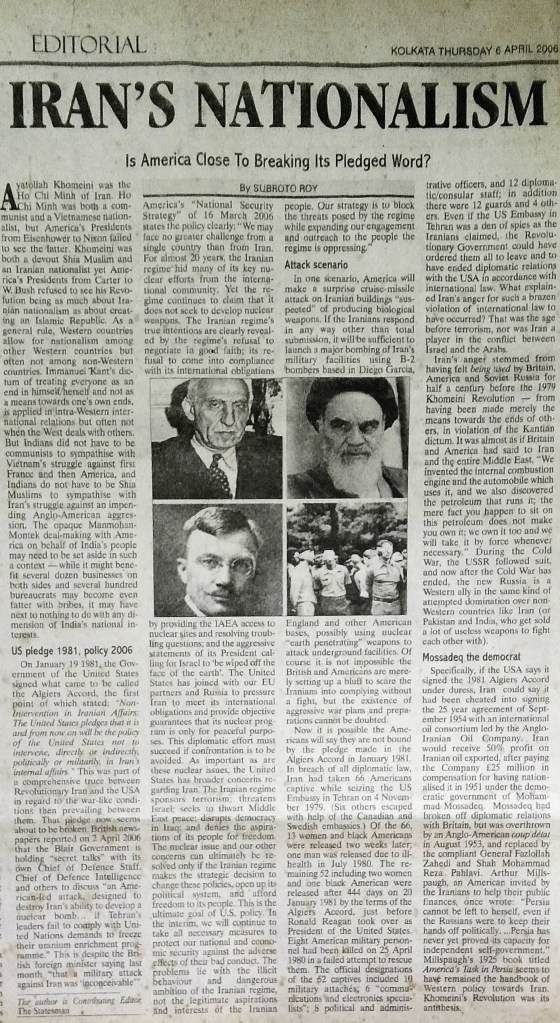

In contrast to Maulana Maudoodi saying Islam was “the very antithesis of secular Western democracy”, Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan (1895-1951)[11] during his first official visit in 1950 to North America was to say the new Pakistan, because it was Muslim, held Asia’s greatest democratic potential:

“At present there is no democracy in Asia which is more free and more unified than Pakistan; none so free from moral doubts and from strains between the various sections of the people.”

He told his audiences Pakistan was created because Hindus were people wedded to caste-differences where Pakistanis as Muslims had an egalitarian and democratic disposition:

“The Hindus, for example, believe in the caste system according to which some human beings are born superior to others and cannot have any social relations with those in the lower castes or with those who are not Hindus. They cannot marry them or eat with them or even touch them without being polluted. The Muslims abhor the caste system, as they are a democratic people and believe in the equality of men and equal opportunities for all, do not consider a priesthood necessary, and have economic laws and institutions which recognize the right of private ownership and yet are designed to promote the distribution of wealth and to put healthy checks on vast unearned accumulations… so the Hindus and the Muslims decided to part and divide British India into two independent sovereign states… Our demand for a country of our own had, as you see, a strong democratic urge behind it. The emergence of Pakistan itself was therefore the triumph of a democratic idea. It enabled at one stroke a democratic nation of eighty million people to find a place of its own in Asia, where now they can worship God in freedom and pursue their own way of life uninhibited by the domination or the influence of ways and beliefs that are alien or antagonistic to their genius.” [12]

President Ayub Khan would state in similar vein on 18 November 1966 at London’s Royal Institute of International Affairs:

“the root of the problem was the conflicting ideologies of India and Pakistan. Muslim Pakistan believed in common brotherhood and giving people equal opportunity. India and Hinduism are based on inequality and on colour and race. Their basic concept is the caste system… Hindus and Muslims could never live under one Government, although they might live side by side.”

Regarding J&K, Liaquat Ali Khan on November 4 1947 broadcast from here in Lahore that the 1846 Treaty of Amritsar was “infamous” in having caused an “immoral and illegal” ownership of Jammu & Kashmir. He, along with Mr Jinnah, had called Sheikh Abdullah a “goonda” and “hoodlum” and “Quisling” of India, and on February 4 1948 Pakistan formally challenged the sovereignty of the Dogra dynasty in the world system of nations. In 1950 during his North American visit though, the Prime Minister allowed that J&K was a “princely state” but said

“culturally, economically, geographically and strategically, Kashmir – 80 per cent of whose peoples like the majority of the people in Pakistan are Muslims – is in fact an integral part of Pakistan”;

“(the) bulk of the population (are) under Indian military occupation”.

Pakistan’s official self-image, portrayal of India, and position on J&K may have not changed greatly since her founding Prime Minister’s statements. For example, in June 2005 the website of the Government of Pakistan’s Permanent Mission at the UN stated:

“Q: How did Hindu Raja (sic) become the ruler of Muslim majority Kashmir?

A: Historically speaking Kashmir had been ruled by the Muslims from the 14th Century onwards. The Muslim rule continued till early 19th Century when the ruler of Punjab conquered Kashmir and gave Jammu to a Dogra Gulab Singh who purchased Kashmir from the British in 1846 for a sum of 7.5 million rupees.”

“India’s forcible occupation of the State of Jammu and Kashmir in 1947 is the main cause of the dispute. India claims to have ‘signed’ a controversial document, the Instrument of Accession, on 26 October 1947 with the Maharaja of Kashmir, in which the Maharaja obtained India’s military help against popular insurgency. The people of Kashmir and Pakistan do not accept the Indian claim. There are doubts about the very existence of the Instrument of Accession. The United Nations also does not consider Indian claim as legally valid: it recognises Kashmir as a disputed territory. Except India, the entire world community recognises Kashmir as a disputed territory. The fact is that all the principles on the basis of which the Indian subcontinent was partitioned by the British in 1947 justify Kashmir becoming a part of Pakistan: the State had majority Muslim population, and it not only enjoyed geographical proximity with Pakistan but also had essential economic linkages with the territories constituting Pakistan.”

India, a country dominated by the hated-Hindus, has forcibly denied Srinagar Valley’s Muslim majority over the years the freedom to become part of Muslim Pakistan – I stand here to be corrected but, in a nutshell, such has been and remains Pakistan’s official view and projection of the Kashmir problem over more than sixty years.[13]

Part II

-

India’s Point of View: British Negligence/Indifference during the Transfer of Power, A Case of Misgovernance in the Chaotic Aftermath of World War II

(a) Rhetoric: Whose Pakistan? Which Kashmir?

(b) Law: (i) Liaquat-Zafrullah-Abdullah-Nehru United in Error Over the Second Treaty of Amritsar! Dogra J&K subsists Mar 16 1846-Oct 22 1947. Aggression, Anarchy, Annexations: The LOC as De Facto Boundary by Military Decision Since Jan 1 1949. (ii) Legal Error & Confusion Generated by 12 May 1946 Memorandum. (iii) War: Dogra J&K attacked by Pakistan, defended by India: Invasion, Mutiny, Secession of “Azad Kashmir” & Gilgit, Rape of Baramulla, Siege of Skardu.

-

Politics: What is to be Done? Towards Truths, Normalisation, Peace in the 21st Century

The Present Situation is Abnormal & Intolerable. There May Be One (and Only One) Peacable Solution that is Feasible: Revealing Individual Choices Privately with Full Information & Security: Indian “Green Cards”/PIO-OCI status for Hurriyat et al: A Choice of Nationality (India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran). Of Flags and Consulates in Srinagar & Gilgit etc: De Jure Recognition of the Boundary, Diplomatic Normalisation, Economic & Military Cooperation.

-

Appendices:

(a) History of Jammu & Kashmir until the Dogra Native State

(b) Pakistan’s Allies (including A Brief History of Gilgit)

(c) India’s Muslim Voices

(d) Pakistan’s Muslim Voices: An Excerpt from the Munir Report

[1] EIJ Rosenthal, Islam in the Modern National State, 1965, pp.196-197.

[2] A contemporary of Mohammad Ibn Abdal Wahhab of Nejd.

[3] Francis Robinson in WE James & Subroto Roy, Foundations of Pakistan’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s, 1993, p. 36. Indeed Barelwi had created a proto-Pakistan in NorthWest India one hundred years before the Pakistan Movement. “In the later 1820s the movement became militant, regarding jihad as one of the basic tenets of faith. Possibly encouraged by the British, with whom the movement did not feel powerful enough to come to grips at the outset, it chose as the venue of jihad the NW frontier of the subcontinent, where it was directed against the Sikhs. Barelwi temporarily succeeded in carving out a small theocratic principality which collapsed owing to the friction between his Pathan and North Indian followers; and he was finally defeated and slain by the Sikhs in 1831″ (Aziz Ahmed, in AL Basham (ed) A Cultural History of India 1976, p. 384). Professor Robinson answered a query of mine in an email of 8 August 2005: “the fullest description of this is in Mohiuddin Ahmad, Saiyid Ahmad Shahid (Lucknow, 1975), although practically everyone who deals with the period covers it in some way. Barelwi was the Amir al-Muminin of a jihadi community which based itself north of Peshawar and for a time controlled Peshawar. He called his fellowship the Tariqa-yi Muhammadiya. Barelwi corresponded with local rulers about him. After his death at the battle of Balakot, it survived in the region, at Sittana I think, down to World War One.”

[4] Rosenthal, ibid., p 235

[5] Germans

[6] Events remote from India’s history and geography, namely, the rise of Hitler and the Second World War, had contributed between 1937 and 1947 to the change of fortunes of the Muslim League and hence of all the people of the subcontinent. The British had long discovered that mutual antipathy between Muslims and Hindus could be utilised in fashioning their rule; specifically that organisation and mobilisation of Muslim communal opinion was a useful counterweight to any pan-Indian nationalism emerging to compete with British authority. As early as 1874, long before Allan Octavian Hume ICS conceived the Indian National Congress, John Strachey ICS observed “The existence side by side of these (Hindu and Muslim) hostile creeds is one of the strong points in our political position in India. The better classes of Mohammedans are a source of strength to us and not of weakness. They constitute a comparatively small but an energetic minority of the population whose political interests are identical with ours.” By 1906, when a deputation of Muslims headed by the Aga Khan first approached the British pleading for communal representation, Minto the Viceroy replied: “I am as firmly convinced as I believe you to be that any electoral representation in India would be doomed to mischievous failure which aimed at granting a personal enfranchisement, regardless of the beliefs and traditions of the communities composing the population of this Continent.” Minto’s wife wrote in her diary the effect was “nothing less than the pulling back of sixty two millions of (Muslims) from joining the ranks of the seditious opposition.” (The true significance of Maulana Azad may have been that he, precisely at the same time, did indeed feel within himself the nationalist’s desire for freedom strongly enough to want to join the ranks of that seditious opposition.)

[7] “That geographically contiguous units are demarcated into regions which should be so constituted, with such territorial readjustments as may be necessary, that the areas in which the Muslims are numerically in a majority, as in the North-Western and Eastern zones of India should be grouped to constitute Independent States in which the constituent units shall be autonomous and sovereign”.

[8] Robinson ibid, pp. 43-44.

[9] In the “Indian India” of the Native Princes, Hari Singh and others who sent troops to fight as part of British armies (and who were nominal members of Churchill’s War Cabinet) would have their vanities flattered, while Sheikh Abdullah’s rebellion against Dogra rule would be ignored. See seq. And in British India, Mr Jinnah the conservative Anglophile and his elitist Muslim League would be backed, while the radicalised masses of the Gandhi-Bose-Nehru Congress suppressed as a nuisance.

[10] An anthology about Lahore reports memories of a murderous mob arriving at a wealthy man’s home to be placated with words like “They are Parsis not Hindus, no need to kill them…”

[11] An exact contemporary of Chaudhury Rahmat Ali.

[12] Pakistan, Harvard University Press, 1950.

[13] It is not far from this to a certain body of sentiments frequently found, for example, as recently as February 5 2011: “To observe the Kashmir Solidarity Day, various programs, rallies and protests will be held on Saturday (today) across the city to support the people of Kashmir in their struggle against the Indian occupation of their land. Various religious, political, social and other organizations have arranged different programs to highlight the atrocities of Indian occupant army in held Jammu and Kashmir where about 800,000 Indian soldiers have been committing atrocities against innocent civilians; killing, wounding and maiming tens of thousands of people; raping thousands of women and setting houses, shops and crops on fire to break the Kashmiris’ will to fight for their freedom…Jamat-ud-Dawah…leaders warned that a ‘jihad’ would be launched if Kashmir was not liberated through civil agitation…the JuD leaders said first the former President, Pervez Musharraf, and now the current dispensation were extending the olive branch to New Delhi despite the atrocities on the Kashmiri people….the Pakistani nation would (never compromise on the issue of Kashmir and) would continue to provide political, moral and diplomatic support to the Kashmiri people.”

My father after presenting his credentials to President Kekkonen

November 7, 2011 — drsubrotoroyOn 14 September 1973 my father presented his credentials as “Ambassadeur extraordinaire et plenepotentiaire de l’Inde” to the President of the Republic of Finland, His Excellency Urho Kekkonen (1900-1986).

My father’s career included a half dozen or so years spent with Indian Oxygen and the Tatas in Jamshedpur (where he met my mother’s family), followed by a dozen years starting in 1942 with the Government of India (as a “Class I Grade 1 officer”) in the war-time Ministry of Supply and later the Ministry of Commerce, followed by little more than two decades in the new Indian Foreign Service.

He has been a man of aesthetic taste and good manners; looking back upon his foreign service career through postings in Tehran, Ottawa, Colombo, Dhaka, Stockholm, Odessa, Paris and Helsinki, I think his aristocratic sensibility made him a “natural diplomat”.

(It is not a sensibility I have felt myself sharing much; he had wished me to follow in his footsteps but I rarely have wished to be diplomatic in my pronouncements!)

There will be more of my father’s experiences here in due course,

https://independentindian.com/life-of-mk-roy-19152012-indian-aristocrat-diplomat-birth-centenary-concludes-7-nov-2016/

especially during the early years of independent India, e.g. with Zafrullah Khan at Karachi airport in 1947, in the evacuation of Hindu refugees from Karachi during Partition, handling of the Indian diplomatic mission in Dhaka during the 1965 war

https://independentindian.com/life-of-mk-roy-19152012-indian-aristocrat-diplomat-birth-centenary-concludes-7-nov-2016/india-pakistan-diplomacy-during-the-1965-war-the-mk-roy-files/

My Seventy Four Articles, Books (now in pdf 2021), Notes Etc on Kashmir, Pakistan, & of course, India (plus my undelivered Lahore lectures)

October 13, 2011 — drsubrotoroyThe most important of these are in the newspapers and/or at this site too. I will try to have everything reproduced here.

00) https://independentindian.com/2015/03/03/pakistans-indias-illusions-of-power-psychosis-vs-vanity/

0) India-Pakistan Diplomacy During the 1965 War: the MK Roy Files, at this site

1) https://independentindian.com/2011/11/22/pakistans-point-of-view-or-points-of-view-on-kashmir-my-as-yet-undelivered-lahore-lecture-part-i/

2) Law, Justice and Jammu & Kashmir (2006)

https://independentindian.com/2006/07/03/law-justice-and-jk/

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=152464726125

Monday, October 5, 2009

3) Solving Kashmir: On an Application of Reason (2005)

https://independentindian.com/2005/12/03/solving-kashmir-on-an-application-of-reason/

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=152462776125

Monday, October 5, 2009

4) My (armchair) experience of the 1999 Kargil war (Or, How the Kargil effort got a little help from a desktop)

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=388161476125

Thursday, April 29, 2010

5) Understanding Pakistan (2006)

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=152348161125

Monday, October 5, 2009

6) Pakistan’s Allies (2006)

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=152345826125

Monday, October 5, 2009

7) History of Jammu & Kashmir

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=152343836125

Monday, October 5, 2009

8) from 30 years ago, now in pdf

Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s edited by Subroto Roy & William E James

Foundations of Pakistan’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s edited by William E James & Subroto Roy

9) Talking to my student and friend Amir Malik about Pakistan and its problems

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150297082781126

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

10) My thanks to Mr Singh for seeing the optimality of my Kashmir solution

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150271489571126

Sunday, September 4, 2011

11) Zafrullah, my father, and the three frigates: there was no massacre of the Hindu Sindhi refugees in Karachi in 1947

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150265008366126

Saturday, August 27, 2011

12) Conversation with Mr Birinder R Singh about my Kashmir solution

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150259831611126

Saturday, August 20, 2011

13) On the Hurriyat’s falsification of history

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150258949946126

Friday, August 19, 2011

14) Letter from a young Pashtun whose grandfathers were in the 1947 invasion of Kashmir (which the Hurriyat says never happened)

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150258851821126

Friday, August 19, 2011

15) More on my solution

http://www.facebook.com/note.php?note_id=10150258100876126

Thursday, August 18, 2011