“I have a student called Suby Roy…”: Reflections on Frank Hahn (1925-2013), my master in economic theory

January 31, 2013 — drsubrotoroyAmerica has yet to play the demographic card: a few million new immigrants would happily buy up all those bad mortgages

October 3, 2009 — drsubrotoroyFrom Facebook:

Mr Tim Cavanaugh’s clear-headed criticism of a principal government economist’s waffle seems to me apt and exactly on target. E.g. he says: “The real purpose here is Panglossian: to convince you that whatever Power does is the right thing to do, and to discredit the idea that government should ever again reduce its presence in the private sector.”

In an article dated Sep 18 2008 titled “October 1929? Not!”, I argued “that the American economy and the world economy are both incomparably larger today in the value of their capital stock, and there has also been enormous technological progress over eight decades. Accordingly, it would take a much vaster event than the present turbulence — say, something like an exchange of multiple nuclear warheads with Russia causing Manhattan and the City of London to be destroyed — before there was a return to something comparable to the 1929 Crash and the Great Depression that followed.” A few weeks later in “America’s divided economists” I said

“Beyond the short run, the US may play the demographic card by inviting in a few million new immigrants (if nativist feelings hostile to the outsider or newcomer can be controlled, especially in employment). Bad mortgages and foreclosures would vanish as people from around the world who long to live in America buy up all those empty houses and apartments, even in the most desolate or dismal locations. If the US’s housing supply curve has moved so far to the right that the equilibrium price has gone to near zero, the surest way to raise the equilibrium price would be by causing a new wave of immigration leading to a new demand curve arising at a higher level. Such proposals seek to address the problem at its source. They might have been expected from the Fed’s economists. Instead, ESSA speaks of massive government purchase and control of bad assets “downriver”, without any attempt to face the problem at its source. This makes it merely wishful to think such assets can be sold for a profit at a later date so taxpayers will eventually gain. It is as likely as not the bad assets remain bad assets.”

Restoring a worldwide idea of an American dream fuelled by mass immigration may be the surest way for the American economy to restore itself. America was at its best when it was open to mass immigration, and America is at its worst when it treats immigrants with racism and worse.

My One-Semester Microeconomics (Theory of Value) Course for Graduate Engineers Planning to Become MBAs

August 16, 2009 — drsubrotoroyFor a half dozen or so years from about 1996 onwards, I taught graduate engineers a course on microeconomic theory as part of an MBA syllabus. The level would have been that of Varian’s undergraduate text as well as, where possible, Henderson & Quandt’s intermediate text (Postscript: and, I now recall, a little of Arrow & Hahn Chapter 2 if there was time). It was quite successful as most students were very serious and had a more than adequate mathematical background.

Exchange, utility analysis and theory of demand

Rational decisions as constrained optimization

Theory of the firm, technology, profit-maximization, cost-minimization, cost curves

Market equilibrium under competitive conditions

Pricing under Monopoly, Oligopoly

Theory of games

Inter-temporal decision-making

Asset markets : arbitrage and present value

Decision-making under uncertainty

Mean-variance analysis : equilibrium in a market for risky assets

Indian Inflation: Upside Down Economics from New Delhi’s Establishment (2008)

April 16, 2008 — drsubrotoroyIndian Inflation:

Upside Down Economics From The New Delhi Establishment

by

Subroto Roy

First published in two parts in

The Statesman, Editorial Page Special Article,

April 15-16, 2008

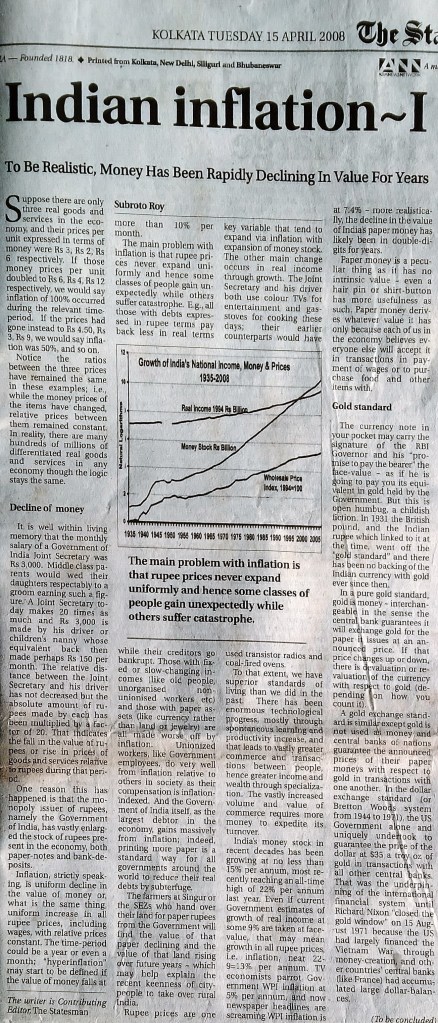

Suppose there are only three real goods and services in the economy, and their prices per unit expressed in terms of money were Rs 3, Rs 2, Rs 6 respectively. If those money prices per unit doubled to Rs 6, Rs 4, Rs 12 respectively, we would say inflation of 100% occurred during the relevant time-period. If the prices had gone instead to Rs 4.50, Rs 3, Rs 9, we would say inflation was 50%, and so on. Notice the ratios between the three prices have remained the same in these examples; i.e., while the money prices of the items have changed, relative prices between them remained constant. In reality, there are many hundreds of millions of differentiated real goods and services in any economy though the logic stays the same.

Decline of money

It is well within living memory that the monthly salary of a Government of India Joint Secretary was Rs 3,000. Middle class parents would wed their daughters respectably to a groom earning such a figure. A Joint Secretary today makes 20 times as much and Rs 3,000 is made by his driver or children’s nanny whose equivalent back then made perhaps Rs 150 per month. The relative distance between the Joint Secretary and his driver has not decreased but the absolute amount of rupees made by each has been multiplied by a factor of 20. That indicates the fall in the value of rupees or rise in prices of goods and services relative to rupees during that period.

One reason this has happened is that the monopoly issuer of rupees, namely the Government of India, has vastly enlarged the stock of rupees present in the economy, both paper-notes and bank-deposits. Inflation, strictly speaking, is uniform decline in the value of money or, what is the same thing, uniform increase in all rupee prices, including wages, with relative prices constant. The time-period could be a year or even a month; “hyperinflation” may start to be defined if the value of money falls at more than 10% per month.

The main problem with inflation is that rupee prices never expand uniformly and hence some classes of people gain unexpectedly while others suffer catastrophe. E.g., all those with debts expressed in rupee terms pay back less in real terms while their creditors go bankrupt. Those with fixed or slow-changing incomes (like old people, unorganised non-unionised workers etc) and those with paper assets (like currency rather than land or jewelry) are all made worse off by inflation. Unionized workers, like Government employees, do very well from inflation relative to others in society as their compensation is inflation-indexed. And the Government of India itself, as the largest debtor in the economy, gains massively from inflation; indeed, printing more paper is a standard way for all governments around the world to reduce their real debts by subterfuge.

The farmers at Singur or the SEZs who hand over their land for paper rupees from the Government will find the value of that paper declining and the value of that land rising over future years ~ which may help explain the recent keenness of city-people to take over rural India.

Rupee prices are one key variable that tend to expand via inflation with expansion of money stock. The other main change occurs in real income through growth. The Joint Secretary and his driver both use colour TVs for entertainment and gas-stoves for cooking these days; their earlier counterparts would have used transistor radios and coal-fired ovens.

To that extent, we have superior standards of living than we did in the past. There has been enormous technological progress, mostly through spontaneous learning and productivity increase, and that leads to vastly greater commerce and transactions between people, hence greater income and wealth through specialization. The vastly increased volume and value of commerce requires more money to expedite its turnover.

India’s money stock in recent decades has been growing at no less than 15% per annum, most recently reaching an all-time high of 22% per annum last year. Even if current Government estimates of growth of real income at some 9% are taken at face-value, that may mean growth in all rupee prices, i.e. inflation, near 22-9=13% per annum. TV economists parrot Government WPI inflation at 5% per annum, and now newspaper headlines are screaming WPI inflation is at 7.4% ~ more realistically, the decline in the value of India’s paper money has likely been in double-digits for years.

Paper money is a peculiar thing as it has no intrinsic value ~ even a hair pin or shirt-button has more usefulness as such. Paper money derives whatever value it has only because each of us in the economy believes everyone else will accept it in transactions in payment of wages or to purchase food and other items with.

Gold standard

The currency note in your pocket may carry the signature of the RBI Governor and his “promise to pay the bearer” the face-value ~ as if he is going to pay you its equivalent in gold held by the Government. But this is open humbug, a childish fiction. In 1931 the British pound, and the Indian rupee which linked to it at the time, went off the “gold standard” and there has been no backing of the Indian currency with gold ever since then.

In a pure gold standard, gold is money ~ interchangeable in the sense the central bank guarantees it will exchange gold for the paper it issues at an announced price. If that price changes up or down, there is devaluation or revaluation of the currency with respect to gold (depending on how you count it).

A gold exchange standard is similar except gold is not used as money and central banks of nations guarantee the announced prices of their paper moneys with respect to gold in transactions with one another. In the dollar exchange standard (or Bretton Woods system from 1944 to 1971), the US Government alone and uniquely undertook to guarantee the price of the dollar at $35 a troy oz of gold in transactions with all other central banks. That was the underpinning of the international financial system until Richard Nixon “closed the gold window” on 15 August 1971 because the US had largely financed the Vietnam War through money-creation, and other countries’ central banks (like France) had accumulated large dollar-balances.

The “gold standard”, “gold exchange standard”, and “dollar exchange standard” are all examples of “fixed” exchange rate systems which came to end in 1971-1972. The price of gold at $35 an oz was obviously unrealistically low, and it shot up at once, and has even reached $1000 an oz recently. Since 1972, the Western world has been on “floating exchange rates” where currencies find their own values and gold is merely one asset among many. Fixed exchange rate systems can lead to speculation, runs against currencies and the irresponsible international export of inflation which floating exchange rate systems tend to avoid because there will tend to be market-determined movement in the exchange-rate instead.

Elite capital flight

India today has neither a proper fixed nor a proper floating exchange-rate system but instead continues a system of highly discriminatory exchange controls. Twenty or thirty million people in our major cities know how to use the present system well enough to exchange their Indian rupees for as much as US $200,000 per annum to send their children and relatives settled abroad as foreign nationals. Plus Indian corporations have been allowed to convert rupees to buy sinking foreign companies. Foreign-currency reserves have vastly climbed too as domestic Indian companies have been allowed to incur foreign-currency denominated debt. Hence the thirty million special people are rather cleverly able to borrow foreign currency with one hand and then transmit it abroad with the other.

The net result is a clear policy of government-induced elite capital flight, unprecedented in its irresponsibility anywhere in world economic history ~ signed, sealed and delivered by the Montek-Manmohan-Chidambaram trio now just as Yashwant-Jaswant-KC Pant and friends had done a little earlier. The Communists would only be worse, as their JNU economists renounce all standard textbook microeconomics and macroeconomics in favour of street-shouting instead.

Outside the thirty million Indians with NRI connections, the average Indian today is disallowed from holding foreign exchange accounts at his/ her local bank or holding or trading in gold or other precious metals freely as he/she may please ~ the physical arrest of Mohun Bagan’s hapless Brazilian footballer by our inimitable Customs officers the other day reveals the ugliness of the situation most poignantly.

Every TV economist in Delhi, Bombay and Kolkata now seems to have a solution about India’s inflation and all sorts of fallacious reasoning is in the air. Some recommend the rupee appreciating or depreciating ~ as if anyone in the country has the faintest idea how elastic imports, exports and capital flows may be in fact to changes in the (controlled) exchange-rate. The Finance Minister and PM keep saying inflation is being “imported” because international commodity prices are high ~ someone should explain to them inflation is “imported” when fixed exchange rates allow transmission through the price-specie flow mechanism, and that is far from being India’s main problem. The extra-constitutional “Planning Commission” has, we may be thankful, remained silent about inflation, and seems to have abandoned earlier misconceptions about using forex reserves for “infrastructure”. The UPA Chair, we may be thankful, also has been silent and admits innocence of all economics, implicitly trusting her PM’s wisdom in all such matters instead.

What no one wants to talk about is the hippopotamus that is present in the room, namely, the chronically diseased state of accounts and public finances of the issuer of India’s paper-rupees, the Union Government, as well as the diseased accounts and finances of more than two dozen State Governments that are subservient to it. The macroeconomic and fiscal policy process that the Congress, BJP, Communists and everyone else in the political class in New Delhi and the State capitals have been presiding over for decades is one that turns normal economics upside down.

What happens in the West is that an estimate of technological progress and population growth is made by policy-makers, then an “acceptable” or “unavoidable” or “natural” rate of inflation is added (the figure of monetary change needed for efficiency in the real economy so relative prices adjust to equilibrium in response to demand and supply changes), then a monetary growth target is set, to which the fiscal authority ~ i.e. the legislature handling the Government’s budget ~ must adjust taxation and spending plans accordingly.

What has been happening in India every year for decades is that each of some two dozen state legislatures runs up a large deficit, which are all added up and passed on to the “Centre”; the “Centre” and its “Yojana Bhavan”, at the behest of every conceivable organised interest-group with access in Delhi especially government unions and the military, runs up its own vastly larger fiscal deficit, and then this grand total of fiscal-deficits is offered to the Reserve Bank at the end of a loaded pistol ~ to pay for one way or another via new public debt creation and money printing. Subtract the WPI rate from the Money Supply Growth rate and government spokesmen and their businessmen friends then exclaim that the economy must try to reach the difference as its “warranted” growth rate! It is all economics upside down from people who have either learnt nothing significant in the subject or forgotten whatever little they once did.

Fragile financial state

The net result has been a banking system (mostly nationalized) in which the asset side of banks’ balance-sheets is made up almost entirely of rather dubious government debt, interest payments on which are received every year from fresh money-printing. The liability side of those balance-sheets consists of course of customer-deposits. In this fragile monetary and financial state, a government-induced capital flight has been allowed to continue under pretence of liberalization ~ with Indian companies being allowed to borrow from foreign markets many times their domestic rupee-denominated net worth by which to acquire ailing foreign companies and brands. Furthermore, there has been a massive fiscal effect as vast new Government spending programs ~ like buying foreign aircraft carriers, fighter-jets or passenger aircraft or writing off farm loans ~ come to be announced and absorbed into expectations of future inflation. A monetary meltdown is what the present author cautioned against in 1990-1995 and again, publicly, in 2000-2005. Economics, candidly treated, tells us not only that there is no such thing as a free lunch but also that chickens come home to roost.

Articles of related interest include “Against Quackery”, “India’s Macroeconomics”, “Fiscal Instability”, “Indian Money and Credit”, “Indian Money and Banking”, “The Dream Team: A Critique” etc. See https://independentindian.com/2013/11/23/coverage-of-my-delhi-talk-on-3-dec-2012/

Milton Friedman: A Man of Reason, 1912-2006

November 22, 2006 — drsubrotoroyA Man of Reason

Milton Friedman (1912-2006)

First published in The Statesman, Perspective Page Nov 22 2006

Milton Friedman, who died on 16 November 2006 in San Francisco, was without a doubt the greatest economist after John Maynard Keynes. Before Keynes, great 20th century economists included Alfred Marshall and Knut Wicksell, while Keynes’s contemporaries included Irving Fisher, AC Pigou and many others. Keynes was followed by his younger critic FA Hayek, but Hayek is remembered less for his technical economics as for his criticism of “socialist economics” and contributions to politics. Milton Friedman more than anyone else was Keynes’s successor in economics (and in applied macroeconomics in particular), in the same way David Ricardo had been the successor of Adam Smith. Ricardo disagreed with Smith and Friedman disagreed with Keynes, but the impact of each on the direction and course both of economics and of the world in which they lived was similar in size and scope.

Friedman’s impact on the contemporary world may have been largest through his design and advocacy as early as 1953 of the system of floating exchange-rates. In the early 1970s, when the Bretton Woods system of adjustable fixed exchange-rates collapsed and Friedman’s friend and colleague George P. Shultz was US Treasury Secretary in the Nixon Administration, the international monetary system started to become of the kind Friedman had described two decades earlier. Equally large was Friedman’s worldwide impact in re-establishing concern about the frequent cause of macroeconomic inflation being money supply growth rates well above real income growth rates. All contemporary talk of “inflation targeting” among macroeconomic policy-makers since the 1980s has its roots in Friedman’s December 1967 presidential address to the American Economic Association. His main empirical disagreement with Keynes and the Keynesians lay in his belief that people held the intrinsically worthless tokens known as “money” largely in order to expedite their transactions and not as a store of value – hence the “demand for money” was a function mostly of income and not of interest rates, contrary to what Keynes had suggested in his 1930s analysis of “Depression Economics”. It is in this sense that Friedman restored the traditional “quantity theory” as being a specific theory of the demand for money.

Friedman’s main descriptive work lay in the monumental Monetary History of the United States he co-authored with Anna J. Schwartz, which suggested drastic contractions of the money supply had contributed to the Great Depression in America. Friedman made innumerable smaller contributions too, the most prominent and foresighted of which had to do with advocating larger parental choice in the public finance of their children’s school education via the use of “vouchers”. The modern Friedman Foundation has that as its main focus of philanthropy. The emphasis on greater individual choice in school education exemplified Friedman’s commitments both to individual freedom and the notion of investment in human capital.

Friedman had significant influences upon several non-Western countries too, most prominently India and China, besides a grossly misreported episode in Chile. As described in his autobiography with his wife Rose, Two Lucky People (Chicago 1998), Friedman spent six months in India in 1955 at the Government of India’s invitation during the formulation of the Second Five Year Plan. His work done for the Government of India came to be suppressed for the next 34 years. Peter Bauer had told me during my doctoral work at Cambridge in the late 1970s of the existence of a Friedman memorandum, and N. Georgescu-Roegen told me the same in America in 1980, adding that Friedman had been almost insulted publicly by VKRV Rao at the time after giving a lecture to students on his analysis of India’s problems.

When Friedman and I met in 1984, I asked him for the memorandum and he sent me two documents. The main one dated November 1955 I published in Hawaii on 21 May 1989 during a project on a proposed Indian “perestroika” (which contributed to the origins of the 1991 reform through Rajiv Gandhi), and was later published in Delhi in Foundations of India’s Political Economy: Towards an Agenda for the 1990s, edited by myself and WE James.

The other document on Mahalanobis is published in The Statesman today for the first time, though there has been an Internet copy floating around for a few years. The Friedmans’ autobiography quoted what I said in 1989 about the 1955 memorandum and may be repeated: “The aims of economic policy (in India) were to create conditions for rapid increase in levels of income and consumption for the mass of the people, and these aims were shared by everyone from PC Mahalanobis to Milton Friedman. The means recommended were different. Mahalanobis advocated a leading role for the state and an emphasis on the growth of physical capital. Friedman advocated a necessary but clearly limited role for the state, and placed on the agenda large-scale investment in the stock of human capital, encouragement of domestic competition, steady and predictable monetary growth, and a flexible exchange rate for the rupee as a convertible hard currency, which would have entailed also an open competitive position in the world economy… If such an alternative had been more thoroughly discussed at the time, the optimal role of the state in India today, as well as the optimum complementarity between human capital and physical capital, may have been more easily determined.”

A few months before attending my Hawaii conference on India, Friedman had been in China, and his memorandum to Communist Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and two-hour dialogue of 19 September 1988 with him are now classics republished in the 1998 autobiography. Also republished there are all documents relating to Friedman’s six-day academic visit to Chile in March 1975 and his correspondence with General Pinochet, which speak for themselves and make clear Friedman had nothing to do with that regime other than offer his opinion when asked about how to reduce Chile’s hyperinflation at the time.

My association with Milton has been the zenith of my engagement with academic economics, with e-mails exchanged as recently as September. I was a doctoral student of his bitter enemy yet for over two decades he not only treated me with unfailing courtesy and affection, he supported me in lonely righteous battles: doing for me what he said he had never done before, which was to stand as an expert witness in a United States Federal Court. I will miss him much though I know that he, as a man of reason, would not have wished me to.

Subroto Roy

Announcement of My “Hahn Seminar”, 1976 November 17

November 17, 1976 — drsubrotoroyFrank Hahn believed in throwing students in at the deep end — or so it seemed to me when, within weeks of my arrival at Cambridge as a 21 year old Research Student, he insisted I present my initial ideas on the foundations of monetary theory at his weekly seminar. I was petrified but somehow managed to give a half-decent lecture before a standing-room only audience in what used to be called the “Keynes Room” in the Cambridge Economics Department.

(It helped that a few months earlier, as a final year undergraduate at the LSE, I had been required to give a lecture at ACL Day’s Seminar on international monetary economics. It is a practice I came to follow with my students in due course, as there may be no substitute in learning how to think while standing up.)

I shall try to publish exactly what I said at my Hahn-seminar when I find the document; broadly, it had to do with the crucial problem Hahn had identified a dozen years earlier in Patinkin’s work by asking what was required for the price of money to be positive in a general equilibrium, i.e. why do people everywhere hold and use money when it is intrinsically worthless. Patinkin’s utility function had real money balances appearing along with other goods; Hahn’s “On Some Problems of Proving the Existence of an Equilibrium in a Monetary Economy” in Theory of Interest Rates (1965), was the decisive criticism of this, where he showed that Patinkin’s formulation could not ensure a non-zero price for money in equilibrium. Hence Patinkin’s was a model in which money might not be held and therefore failed a vital requirement of a monetary economy.

The announcement of my seminar was scribbled by a young Cambridge lecturer named Oliver Hart, later a distingushed member of MIT and Harvard University.