Towards a Highly Transparent Fiscal & Monetary Framework for India’s Union & State Governments

An address by Dr Subroto Roy to

the Conference of State Finance Secretaries, Reserve Bank of India, Mumbai, 29 April 2000.

It is a great privilege to speak to this distinguished gathering of Finance Secretaries and economic policy-makers here at the Reserve Bank today. I should like to begin by thanking the Hon’ble Governor Dr Bimal Jalan and the Hon’ble Deputy Governor Dr YV Reddy for their kind invitation for me to do so. I should also like to record here my gratitude to their eminent predecessor, the Hon’ble Governor of Andhra Pradesh, Dr C Rangarajan, for his encouragement of my thinking on these subjects over several years.

My aim will be to share with you and seek your help with my continuing and very incomplete efforts at trying to comprehend as clearly as possible the major public financial flows taking place between the Union of India and each of its constituent States. I plan to show you by the end of this discussion how all the information presently contained in the budgets of the Union and State Governments of India, may be usefully transformed one-to-one into a fresh modern format consistent with the best international practices of government accounting and public budgeting.

I do not use the term “Central Government”, because it is a somewhat sinister anachronism left over from British times. When we were not a free nation, there was indeed a Central Government in New Delhi which took its orders from London and gave orders to its peripheral Provinces as well as to the British “Residents” parked beside the thrones of those who were called “Indian Princes”.

Free India has been a Union of States. There is a Government of the whole Union and there is a Government of each State. The Union is the sovereign and the sole international power, while the States, as political subdivisions of the Union, also possess certain sub-sovereign powers; as indeed do their own subdivisions like zilla parishads, municipalities and other local bodies in smaller measure.

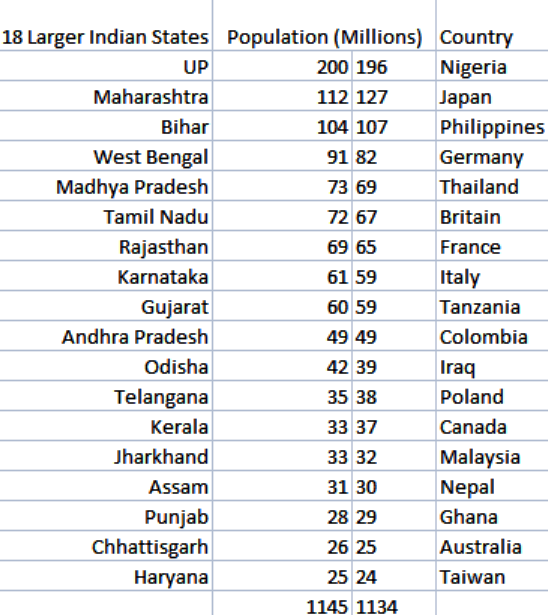

Our 15 large States, which account for 97% of the population of the country, have an average of something like 61 million citizens each, which is vastly more than most countries of the world. In size of population at least, we are like 15 Frances or 15 Britains put together. The Indian Republic is unique or sui generis in that there has never been in history any attempt at federalism or democracy with such sheer large numbers of people involved.

In such a framework the citizen is supposed to feel a voter and a taxpayer at different levels, owing loyalty and taxes to both the national unit and the subdivisions in which he or she resides. In exchange, government at different levels is expected to provide citizens with public goods and services in appropriate measure. The problem of optimal fiscal decentralisation in India as elsewhere is one of allocating to each level of government the power to tax and responsibility to provide, public goods and services most appropriate to that level of government given the availability of information of resources and citizens’ preferences.

In parallel, a problem of optimal monetary decentralisation may be identified as that of allocating between an autonomous Central Bank and its regional or even State-level affiliates or subsidiaries, the power to finance through money-creation the deficits, if any, of the Union and State Governments respectively. It is not impossible to imagine a world in which individual State deficits did not flow into the Union deficit as a matter of course, but instead were intended to be financed more or less independently of the Union budget from a single-window source. There would be a clear conceptual independence between the Union and State levels of public action in the country. In such a world, the Union Government might approach a constitutionally autonomous national-level Central Bank to finance its deficit, while individual State Governments did something analogous with respect to autonomous regional or even State-level Central Banks which would be affiliates or subsidiaries of the national Central Bank.

This is similar to the intended model of the United States Federal Reserve System when it started 90 years ago, though it has not worked like that, in part because of the rapid rise to domination by the New York Federal Reserve relative to the other 11 regional Federal Reserve Banks.

A more radical monetary step would be to contemplate a “Reverse Euro” model by which a national currency issued by the national-level Central Bank acts in parallel with a number of regional or State-level currencies with full convertibility and floating exchange-rates guaranteed between all of them in a world of unhindered mobility of goods and factors.

However, these are very incomplete and theoretical thoughts which perhaps deserve to be shelved for the time being.[1] What necessitates this kind of discussion is after all not something theoretical but rather the practical ground realities of our country’s fiscal and monetary position, something of which this audience will be far better aware than am I.

Economic and political analysis suggests that managing a process of public financial decision-making requires a coincidence of the people who have the best information with the people who have the authority to act. In other words, decision-makers need to have relevant, reliable and timely information made available to them, and then they need to be considered accountable for the decisions made on that basis.

In a democracy like ours, the locus of economic policy decision-making must be Parliament and the State legislatures. Academics, civil servants, journalists, special interest groups, this or that business or industrial lobbyist or foreign management consultant can all have their say — but consensus on the direction and nature of economic policy, if it is to be genuine, has to ultimately emerge out of the legislative process on the basis of reasonable, well-informed discussion and debate, given full relevant timely information. The proper source of all economic policy decisions and initiatives is Parliament, the State legislatures and local government bodies — not this or that lobby or interest-group which may be vocal or powerful enough to be heard at a given time in New Delhi or some State capital-city.

Our 1950 Constitution was a marvellous document in its time and it has worked tolerably well. It defined the functions of government in India in accordance with the main parameters of normative public finance.

Economics ascribed a quite extensive traditional role to Government, the most important functions being collective and individual security, followed by all activities which in the words of Adam Smith,

“though they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expence to any individual or small number of individuals, and which it, therefore, cannot be expected that any individual or small number of individuals should erect or maintain.” (Wealth of Nations, V.i.c., 1776)

Our 1950 Constitution defined the Union’s responsibilities to be

External Security;

Foreign Relations & Trade;

Supreme Court & Domestic Security;

Debt Service, Foreign & Domestic;

National Infrastructure;

Communications & Broadcasting;

Atomic Energy;

Public Sector Industries;

Banking; Currency & Finance;

Archives; Surveys & National Institutions;

National Universities;

National Civil Services & Administration.

Each State’s responsibilities were

High Courts & Lower Judiciary;

Police; Civil Order; Prisons;

Water; Sanitation; Health;

State Debt Service;

Intra-State Infrastructure & Communications;

Local Government;

Liquor & Other Public Sector Industries; Trade; Local Banking & Finance;

Land; Agriculture; Animal Husbandry;

Libraries, Museums, Monuments;

State Civil Service & Administration.

Some duties were supposed to be shared by the Union with each State, including

Criminal Law;

Civil & Family Law, Contracts & Torts;

Forests & Environmental Protection;

Unemployment & Refugee Relief;

Electricity;

Education.

But the authors of the 1950 Constitution could not have envisaged the nature of present problems, or foreseen in those early years what we would have become like today. Our fiscal system has become such that a few clauses may have led to an impossibly complex centralization of fiscal power and information. Not only did the 1950 Constitution identify agendas of the Union and State Governments, it also dictated the procedure of decision-making and it is this which may have become intractable over 50 years. Under Article 280, a Finance Commission is appointed every five years whose task is to try to efficiently and equitably allot tax revenues collected by the Union downwards to the States and laterally between the States. Members of Finance Commissions have been elder statesmen of high reputation and integrity, yet the practical impossibility of their task has made their actions seem to all observers to be clouded in mystery and perhaps muddle. As one recent member, Justice Qureshi, has candidly stated

“it is humanly impossible for a person to understand the problems of the Centre and the 25 States and take a decision thereon within such a short time” (Ninth Finance Commission, Issues and Recommendations, p.350).

No matter how competent or well-meaning a Finance Commission’s members may be, their purpose may be stymied by the overload of information and overcentralisation of authority that has come to take place. As a result, it may have been inevitable that Government has ended up doing what it need not have done at the expense concomitantly of failing to do what only Government could or must have done.

The present situation is such that, despite the best efforts of the Reserve Bank and other Government agencies, there may be a gross lack of timely, relevant and reliable information reaching all decision-makers including the ordinary citizen, who as voter and taxpayer is the cornerstone of the fiscal system. My own inquiry started when Mr. Hubert Neiss, then Central Asia Director at the IMF, hired me as a consultant in December 1992. He told me the IMF was naturally concerned about India’s national budget deficit, but no one seemed to quite know how this related precisely to the budgets of the different States whose deficits seemed to be flowing into it. By its terms of reference, the IMF could not inquire into India’s States’ budgets and I did not do so in my work with them, but the import of his question remained in my thinking. Later I found similar questions being asked at the World Bank. I do not think it a great secret to state that there may be a great deal of simple puzzlement about the workings of our fiscal and monetary system on the part of observers and decision-makers who may be concerned about India’s fiscal position.

Among both public decision-makers and ordinary citizens right across the length and breadth of our country, a severe and widespread lack of information about and comprehension of India’s basic fiscal and monetary facts seems to exist. This in itself may be a cause of fiscal problems as citizens may not be adequately aware of the link between making their demands for public goods and services on the one hand, and the necessity of finding the resources to fund these goods and services on the other.

In any ultimate analysis, resources for public goods and services in an economy can be found only by diverting the real resources of individual citizens towards public uses. Other than printing fiat money, a national Government can only either tax those citizens who are present today in the population, or, borrow from the capital stock on behalf of unborn generations of future citizens.

West Europe and America are heirs to a long history of political development; yet even there, as Professor James Buchanan has often observed, the idea until has not been grasped until recently that benefits from use of public goods and services are supposed to accrue to citizens from whom resources have been raised. Until the 19th Century,

“government outlay was frequently considered “unproductive”, and there was, by implicit assumption, no return of services to the citizens who were taxed. In a political regime that devotes the bulk of government outlay to the maintenance expenses of a single sovereign, or even of an elite, there is no demonstrable return flow of services to the taxpayers…. Tax principles were discussed as if, once collected, revenues were removed forever from the economy; taxpayers, both individually and in the aggregate, were held to suffer real income loss” (James M. Buchanan, The Demand and Supply of Public Goods, Rand 1968, p. 167).

According to Buchanan, such an undemocratic fiscal model was transformed in the work of the great Swedish economist Knut Wicksell and others by introducing the key assumption of fiscal democracy, namely, that

“those who bear the costs of public services are also the beneficiaries in democratic structures”

Conversely, we may say those who demand public goods and services in a fiscal democracy should also expect to pay for them in real resources. If citizens are aware of taxes only as a burden and come to feel they receive little or nothing from Governments in return, there is a loss of incentive to pay taxes or to stand up and be counted as proud citizens of the country. There is an incentive instead to evade taxes or to flee the country or to cynically believe everything to be corrupt. On the other hand, if citizens demand public goods and services without expecting to contribute resources for their production, this amounts to being no more than a demand to be a free-rider on the general budget.

In our country, we may have been seeing both phenomena. On one hand, there is, rightly or wrongly, a tremendous public cynicism present almost everywhere with respect to expecting effective provision of public goods and services. On the other hand, the idea that the beneficiaries of public goods and services must also, sooner or later, come to bear the costs in terms of taxed resources is far from established so our politics come to often be unreasonable and irresponsible.

Reliable and comprehensible information about the system as a whole and about the contents of public budgets is thus vital for a fiscal democracy to function. In ancient Athens it was said:

“Here each individual is interested not only in his own affairs but in the affairs of the State as well; even those who are mostly occupied with their own business are extremely well-informed on general politics — this is a peculiarity of ours: we do not say that a man who has no interest in politics is a man who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all.” Pericles (Funeral Oration, Thucydides, The Pelopennesian War)

That was the criterion that Pericles defined for ancient Athenian democracy, and I see no reason why in the 21st Century it cannot be met in modern India’s democracy.

This finally brings me to the positive contribution I have promised to make. The aim my attempt to redesign the Union and State’s budgets utilising precisely the same data as available has been to make the fiscal position of all public entities accessible to any interested citizen.

We do not have to say that every Indian citizen, or even every literate and numerate citizen of our country, has to be able to understand the intricacies of the public budgets of his or her State and the Union. But if information is available such that anyone who understands the finances of his own family or his own business enterprise is also reasonably able to understand the public budget then a standard of maximum feasible transparency would have been defined and met.

I have relied on the international normative model developed by our own countryman, Mr. A. Premchand, who retired from the IMF a few years ago, as described in his outstanding book Effective Government Accounting (IMF 1995), where he showed applications for e.g. the USA, New Zealand and Switzerland. What I have done – or rather did in 1997/1998, with the help of a research assistant and a student – is apply that to all of our States and the Union too.[2] What will be seen by way of differences with the present methodology is that there is essentially an Operating Statement, a Financial Statement and a Cash Flow Statement offered for each State and the Union. The financial position and gross fiscal deficit definition emerge rather neatly from this – while there the rather confusing “Development/Non-development” and “Planning/Non-Planning” distinctions have been done away with.

The exercise points to the foundations of a new and fresh federal framework for our Republic. A central new fact of modern India is that many, perhaps most, of our States have developed what is effectively a bipolar division in their legislatures. Voters have also increasingly started to judge Governments not by the personalities they contain but rather by their performance on the job, and, at election-time, have begun to frequently enough shown one side the door in the hope the other side may do better. In such circumstances, there seems no reason in principle why an entity as large as the average State of modern India today cannot be entrusted to legislate and administer a modern tax-system, based especially on the income-tax, and especially taxing income from all sources including agriculture. In a fresh and modern federalism, an elected State Government would have appropriate economic powers to run its own affairs, and be mainly accountable to the legislature whose confidence it requires, and ultimately to voters below.

From an efficiency standpoint, we should want a framework in which repercussions of political turmoil or bad financial management by a State Government to not spill into other States or flow into the Union Government’s own problems of deficit financing. With free mobility of goods and factors throughout the Union, citizens faced with a poorly performing State Government could seek to vote it out of office, or may of course “vote with their feet” by moving their capital or resources to another part of the country. In short, State Governments will be held responsible by their electorates for their expenditures on public goods and services, while having the main powers of domestic taxation in the economy, especially taxes on income from all sources including agriculture.

At the same time, diverse as India is, we are not 15 or 25 separate republics federated together but rather one country all of whose peoples are united by a common geography and a common experience of history. From an equity and indeed national standpoint, we may also want a system which also firmly established that the National Parliament would have to determine how much each citizen should be taxed for the Union to provide public goods and services for the country as a whole, as well as what transfers ought to be made between the States via the Union in the interests of equity given differences in initial resource-endowments between them.

Here again an American example may be useful. As is well-known, the 50 United States each have their own Constitutions governing most intra-State political matters, yet all being inferior in authority to the 1789 Constitution of the United States as duly amended. In India, an author as early as 1888 recommended popular Constitutions for India’s States on the grounds

“where there are no popular constitutions, the personal character of the ruler becomes a most important factor in the government… evils are inherent in every government where autocracy is not tempered by a free constitution.”[3]

We could ask if a better institutional arrangement may occur by each State of India electing its own Constitutional Convention subject naturally to the supervision of the National Parliament and the obvious provision that all State Constitutions be inferior in authority to the Constitution of the Union of India.[4] These documents would then furnish the major sets of rules to govern intra-State political and fiscal decision-making more efficiently. An additional modern reason can be given from the work of Professor James M. Buchanan, namely, that fiscal constitutionalism, and perhaps only fiscal constitutionalism, allows over-riding to take place of the interests of competing power-groups.[5]

State-level Constitutional Conventions in India would provide an opportunity for a realistic assessment to be made by State-level legislators and citizens of the fiscal positions of their own States. Greater recognition and understanding of the plain facts and the desired relationships between income and expenditures, public benefits and public costs, would likely improve the quality of public decision-making at State-levels, sending public resources from destinations which are socially worthless towards destinations which are socially worthwhile. It bears repeating the average size of a large State of India is 61 million people, and almost all existing political Constitutions around the globe furnish rules for far smaller populations than that.

Thank you for your patience. Jai Hind.

[1] Monetary Federalism at Work: F. A. Hayek more than anyone else taught us that relative prices are signals or guides to economic activity — summarizing in a single statistic information about the resources, constraints, expectations and ambitions of market participants. An exchange-rate between two currencies is also a relative price, conveying information about relative market opinions regarding the issuers of the two currencies. Suppose we had two States of India in the fresh kind of federal framework outlined above, which were identical in all respects except one had a larger deficit and so a larger nominal money supply growth. Would that mean the first currency must depreciate relative to the second? Not necessarily; it is not the size of indebtedness that matters but rather the quality of public investment decisions, to which borrowed money has been put. Thus we come to the crux: Suppose we have two States which are identical in all respects except one: State X is found to have an efficient Government, i.e. one which has made relatively good quality public investment decisions, and State Y is found to have one which has made relatively bad quality public investment decisions. In the present amalgamated model of Indian federal finance, no objective distinction can be made between the two, and efficient State Governments are surreptitiously compelled to end up subsidising inefficient ones. In a differentiated federal framework for India, as the different information about the two State Governments comes to be discovered, the X currency will tend to appreciate as resources move towards it while the Y will tend to depreciate as resources move away from it. In an amalgamated model, efficient State Governments lose incentives to remain efficient, while in a differentiated model, inefficient State Governments will gain an incentive not to be inefficient. The present amalgamated situation is such that inefficient States – and this may include not only the State Government but also the State Legislature and the State electorate itself – receive no fiscal incentive to improve themselves. In a differentiated framework, the same inefficient State would face a tangible, visible loss of reserves or depreciation of its currency relative to other States on account of its inefficiency, and thereby have some incentive to mend its ways. I call the proposal given here a “Reverse Euro” model because Europe appears to be moving from differentiated currencies and money supplies to an amalgamated currency and money supply, while the argument given here for India is in the opposite direction. Professor Milton Friedman of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, has had the kindness, at the age of 88, to send me a brilliant and forceful critique of my Reverse Euro idea for India when I requested his comment. Since he is the founder of the flexible exchange-rate system and he has found it too radical, I have shelved it for the time being.

[2] The assistance of Dola Dasgupta and K. Shanmugam is recorded with gratitude.

[3] Surendranath Roy, A History of the Native States of India, Vol I. Gwalior, Calcutta & London: Thacker 1888.

[4] Large amounts of legal and constitutional precedent have built up on issues of a regional or local nature: whether a State legislature should be unicameral or bicameral, what should be its procedures, what days should be State holidays but need not be national holidays, on tenancy, rent control, school standards, health standards and so on ad infinitum. All this body of explicit and implicit local rules and conventions may be duly collected and placed in State-level Constitutions.

[5] James M. Buchanan, Limits to Liberty, Texas, 1978.

A major expansion and reorganization of the judiciary would have to accompany the sort of basic constitutional reform outlined above. Union and State judiciaries would need to be more clearly demarcated, and rules established for review of State-level decisions by Union courts of law. It is common knowledge the judiciary in India is in a state of organizational overload at the point of collapse and dysfunction. An expansion and reorganization of the judiciary to match new Union-State constitutional relations will likely improve efficiency, and therefore welfare levels of citizens.